- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 24, No. 3, 2020. pp. 237-252.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2020.24.3.378

Number of citation : 0The Optimal Degree of Reciprocity in Tariff Reduction

|

School of Economics Singapore Management University |

Abstract

This paper characterizes the optimal reciprocal trade policy in the environment of Melitz (2003) with firm productivity heterogeneity. In particular, without making parametric assumptions on firm productivity distribution, this paper derives the optimal degree of reciprocal tariff reductions that maximize the world welfare. A reciprocal import subsidy raises the industry productivity, lowering aggregate price; a reciprocal import tariff helps correct the markup distortion, increasing nominal income. With all the conflicting effects of import tariffs on welfare considered, the optimal degree of reciprocity in multilateral tariff reduction is shown to be free trade.

JEL Classification: F12, F13, F15

Keywords

Firm Heterogeneity, Reciprocal Trade Policy, Import Tariff, Markup Distortion, Aggregate Productivity

I. INTRODUCTION

This article contributes to the literature of optimal trade policy in the environment of Melitz (2003) with firm productivity heterogeneity. In particular, without making parametric assumptions on firm productivity distribution, this paper derives the optimal degree of reciprocal tariff reductions that maximize the world welfare. A reciprocal import subsidy raises the industry productivity by shifting market shares toward the more productive exporting firms and trimming the least productive firms. On the other hand, a reciprocal import tariff (by a wedge equal to the monopolistic markup) equalizes the opportunity cost of consuming foreign and local varieties, correcting the markup distortion identified by Gros (1987). The two countervailing considerations offset each other at the world aggregate level. Thus, the old doctrine of reciprocal free trade championed in the classical paradigm of perfect competition with homogeneous goods continues to hold up in a world with monopolistic competition and heterogeneous firms.

The optimal trade policy under firm heterogeneity has been analysed by Demidova and Rodríguez-Clare (2009) in a small-country setting and Felbermayr, Jung and Larch (2013) in a large-country setting, under the Pareto assumption for the firm productivity distribution. Their focus is, however, on the

The studies by Baldwin (2005) and Baldwin and Forslid (2006) analysed the impacts of trade liberalization on firm-level dynamics and aggregate welfare. Their analysis suggests that countries gain from reciprocal trade freeness. They, however, model the policy variable in terms of iceberg trade cost (rather than tariffs). This limits the policy option to the non-negative domain, and implies a monotonic relationship between trade freeness and aggregate welfare in this domain. As our analysis below suggests, the strength of trade cost on firm dynamics is not identical to that of tariffs, and trade freeness beyond free trade (with reciprocal positive import subsidy) is suboptimal.

This paper is also related to the work of Bagwell and Lee (2018), who studied the unilateral optimal, jointly optimal, and Nash equilibrium trade policy in the Melitz setup, but with Pareto productivity distribution and an additional competitive sector. They find that starting at global free trade, efficiency is enhanced with small import subsidies. This is contrary to the current paper’s conclusion. This suggests that labor mobility across sectors (or in general, endogenous changes in the size of labor force employed in the Melitz-type sector), a mechanism not present in the current paper, may introduce another incentive for trade intervention. I elaborate on this further after developing the current paper’s theoretical framework.

In Section 2, I start by clarifying the roles played by trade policy, in contrast with iceberg trade cost in the setting of Melitz (2003), before characterizing the optimal reciprocal trade policy. Import tariffs and iceberg trade cost were often taken to be equivalent in the literature following Melitz (2003), and trade liberalization was often modeled as a consequence of exogenous reduction in trade cost. This is contrary to the focus of trade liberalization in practice where trade policy plays a central role and its level is an object of negotiation.

I show in Section 2.3 that import tariffs have a more severe trade-restricting effect than iceberg trade cost, such that the cutoff productivity level for firms to produce is lower and the cutoff productivity level for firms to export is higher. As a result, a larger mass of local firms (varieties) and a smaller mass of competing foreign firms (varieties) can survive with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost.

The characterization of welfare also changes qualitatively when trade cost is replaced by import tariffs (Section 2.4). In particular, one needs to take into account the nominal income change (via tariff revenues) in addition to the aggregate productivity (price) change as the tariff rate varies. Tariff revenues increase nonmonotonically as the tariff increases above the free trade level, while the price decreases non-monotonically as the tariff decreases below the free trade level. The net effect of the two, however, has a unique maximum, and free trade is demonstrated to be the optimal reciprocal policy (Section 2.5). This finding of free trade optimality is nontrivial, given the presence of imperfect competition and price markup on one hand (which tends to encourage the use of import tariffs) and the presence of endogenous intra-industry reallocations of market shares across firms of heterogeneous productivity on the other hand (which tends to encourage the use of import subsidies).

Further discussions of the paper’s mechanisms and their parallels to the literature are provided in Section 2.6. Section 3 concludes.

II. MODEL

1. Setup

In Melitz (2003), it is assumed that there are ( To export to each of the other

To export to each of the other  for firms to export, the mass

for firms to export, the mass

2. Tariffs versus Trade Cost

Let the setup be the same as in Melitz (2003), but let the variable trade cost be replaced by import tariffs. Let  which is also the consumer price at home, but will charge a higher consumer price abroad

which is also the consumer price at home, but will charge a higher consumer price abroad  to reflect the import tariff. The firm sells a quantity

to reflect the import tariff. The firm sells a quantity  is the elasticity of substitution across goods that enter the utility function and equivalently the aggregate quantity index

is the elasticity of substitution across goods that enter the utility function and equivalently the aggregate quantity index

Comparing the above expressions with those in Melitz (2003), we could see that import tariffs differ from iceberg trade cost in two fundamental ways. First, recall that in the case of iceberg trade cost, an exporter receives an export revenue

Second, although both types of trade restriction leads to a higher overseas consumer price

The trade policy studied in this paper corresponds to the multilateral, reciprocal, import policy that is agreed upon by countries and imposed simultaneously against each other. Although the export policy will not be analyzed, the equivalence of an export subsidy (tax) and an import subsidy (tariff) in the current setting is understood. In the current setting with symmetric countries, a country’s aggregate export revenue earned by its exporting firms is equal to its aggregate value of imports f.o.b. from its trading partners. Thus, countries by agreeing to levying a reciprocal import tariff (

3. Characterization of Firm-level Equilibrium

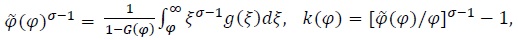

Following the characterization in Melitz (2003), let  and

and  represents the weighted average of firm productivities above a cutoff level

represents the weighted average of firm productivities above a cutoff level  as shown in Melitz (2003). Firms with the productivity level

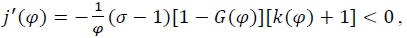

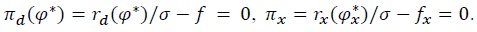

as shown in Melitz (2003). Firms with the productivity level  make just enough variable profits from the domestic market and overseas markets to cover the fixed overhead production cost and the fixed export cost, respectively:

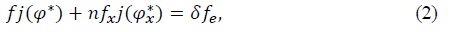

make just enough variable profits from the domestic market and overseas markets to cover the fixed overhead production cost and the fixed export cost, respectively:  These define their relationship:

These define their relationship:

It is assumed that

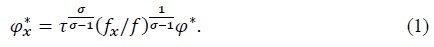

which is the same as in Melitz (2003). Thus, (1) and (2) determine the cutoff productivity levels  It is worth noting that the equilibrium lower cutoff productivity level

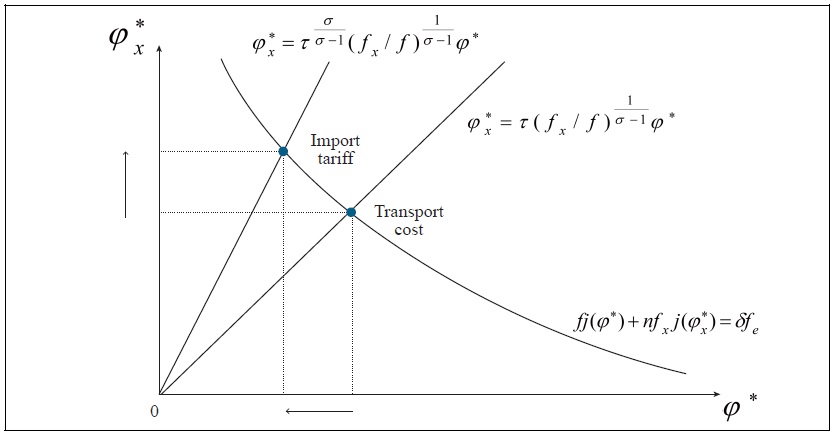

It is worth noting that the equilibrium lower cutoff productivity level  will be higher with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost of the same magnitude, as illustrated in Figure 1. This is because (2) is the same in both cases depicting a negative relationship between the two cutoff productivity levels to maintain a constant expected profit of entry. On the other hand, (1) drawing a positive relationship between the two cutoff productivity levels (derived based on relative market shares) has a higher positive slope with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost. Thus, import tariffs harm exporters and protect local producers more than iceberg trade cost. The average firm profit for successful entrants

will be higher with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost of the same magnitude, as illustrated in Figure 1. This is because (2) is the same in both cases depicting a negative relationship between the two cutoff productivity levels to maintain a constant expected profit of entry. On the other hand, (1) drawing a positive relationship between the two cutoff productivity levels (derived based on relative market shares) has a higher positive slope with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost. Thus, import tariffs harm exporters and protect local producers more than iceberg trade cost. The average firm profit for successful entrants  is therefore lower with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost.

is therefore lower with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost.

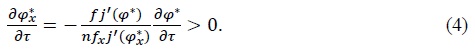

It is straightforward to verify that an increase in the import tariff has qualitatively similar effects as an increase in the iceberg trade cost on all the firm level variables such as  , domestic sales

, domestic sales  For example, an increase in import tariffs will lower the survival cutoff productivity level but raises the bar for firms to export:

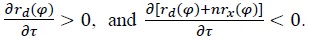

For example, an increase in import tariffs will lower the survival cutoff productivity level but raises the bar for firms to export:

It also increases a firm’s domestic sales, lowers an exporter’s overseas sales, and overall decreases an exporter’s combined domestic and overseas sales:

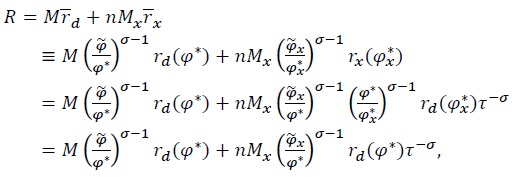

4. Characterization of Aggregate Equilibrium and Welfare

I now characterize the aggregate equilibrium. Let  is lower; thus, the average firm revenue

is lower; thus, the average firm revenue  is lower as well. As a result, a larger mass of local firms (goods)

is lower as well. As a result, a larger mass of local firms (goods)  can be supported with import tariffs compared with iceberg trade cost. On the other hand, the mass of foreign varieties imported from each trading partner

can be supported with import tariffs compared with iceberg trade cost. On the other hand, the mass of foreign varieties imported from each trading partner  is smaller with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost, as both the unconditional probability of export

is smaller with import tariffs than with iceberg trade cost, as both the unconditional probability of export  and the conditional probability of export

and the conditional probability of export

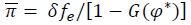

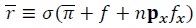

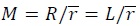

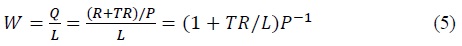

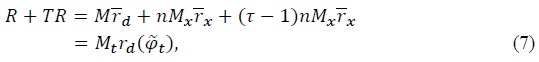

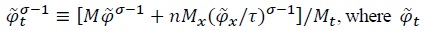

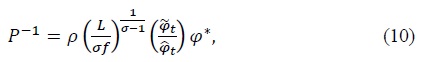

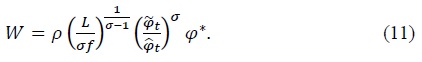

The welfare per capita

reflects the real wage component

where  Let

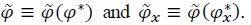

Let  where

where  can be regarded as the weighted average productivity of all firms with their relative output shares as the weights (exporters with a productivity level

can be regarded as the weighted average productivity of all firms with their relative output shares as the weights (exporters with a productivity level

Similarly note that,

with  is the average productivity of all firms weighted by their relative output shares. In the case of iceberg trade cost, there is not such a distinction between (6) and (7); instead, it holds that

is the average productivity of all firms weighted by their relative output shares. In the case of iceberg trade cost, there is not such a distinction between (6) and (7); instead, it holds that  as seen in Melitz (2003). Next, one can verify that

as seen in Melitz (2003). Next, one can verify that

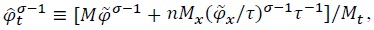

whose expressions are the same as in Melitz (2003), as trade cost and tariffs have the same effect on pricing behaviors of firms. Using (6), (7), and (8), we can show that

5. Optimal Reciprocal Trade Policy

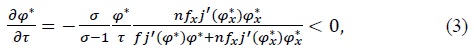

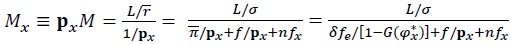

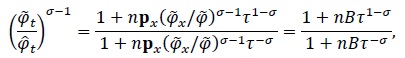

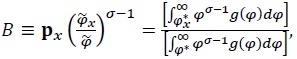

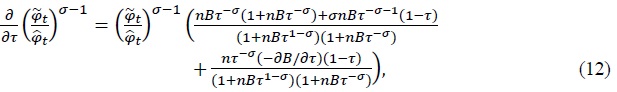

now characterize the comparative statics of the income component and the price component of the welfare as the tariff rate changes. Given the definitions of  note that

note that

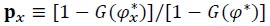

where  which is (roughly speaking) the marketshare weighted cumulative density of exporting firms relative to that of all active firms. Obviously, this decreases in the tariff rate (

which is (roughly speaking) the marketshare weighted cumulative density of exporting firms relative to that of all active firms. Obviously, this decreases in the tariff rate (

which is positive for

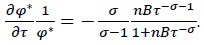

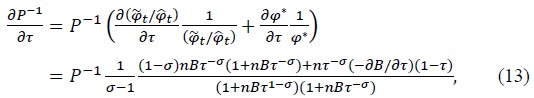

This income effect needs to be weighed against the effect of tariffs on the price level  Using this and (12), it follows that

Using this and (12), it follows that

which is negative for

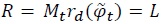

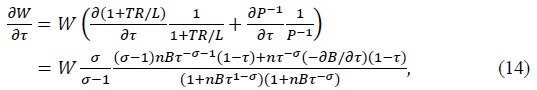

Thus, starting from free trade, there is an incentive to impose an import tariff due to income consideration, but at the same time, there is an incentive to provide an import subsidy due to price consideration. The following derivations show how these two considerations work against each other at different levels of import tariff rates:

where the second equality follows by using the results in (12) and (13). Thus,

and the welfare per capita is maximized at the free trade level. By increasing the import tariff rate above the free trade level, the negative impact of a higher price level outweighs any potential positive impact on income through tariff revenues. Conversely, the negative impact of a lower national income by providing an import subsidy would outweigh any potential positive impact of a lower price level. The optimal reciprocal tariff rate that will maximize every country’s welfare turns out to be zero.

This result is nontrivial given the fact that firms are heterogeneous in their productivities and trade policy may alter the composition of firms and hence the industry aggregate productivity. For example, it may be tempting to argue that a reciprocal import subsidy is beneficial, as it raises the industry productivity by shifting market shares toward the more productive exporting firms and trimming the least productive firms. The result above demonstrates that the positive productivity effect, reflected in lower prices, of an import subsidy would be dominated by the subsidy cost.

On the other hand, a frequently heard argument for an import tariff in a monopolistically competitive setting is the distortion introduced by the price markup. In particular, the price of domestic varieties does not reflect their true opportunity cost but are at a markup above their marginal cost of production, whereas the offshore price of imported varieties reflects the importing country’s true opportunity cost to obtain these goods. An import tariff on foreign varieties equal to the monopolistic markup restores the relative market prices of foreign versus domestic varieties to their relative opportunity costs, and encourages more consumption of local varieties. The result above shows that such potential positive effects on welfare of an import tariff would be more than offset by its negative impact on the aggregate productivity. Thus, the old doctrine for reciprocal free trade established in the classical paradigm of perfect competition with homogeneous goods remains to hold in a world with monopolistic competition and heterogeneous firms.

6. In Relation to the Literature

To understand the paper’s result further in terms of the literature’s language, I now draw the parallel between the paper’s mechanisms to those identified by the literature. First, the incentive to impose import tariffs due to income consideration is akin to the incentive to correct the markup distortion (the discrepancy between the relative market price and the relative opportunity cost of the domestic and foreign varieties) as discussed above. On the other hand, the incentive to provide import subsidy so as to lower the aggregate price is akin to the incentive to correct the entry distortion identified in the literature (where consumers do not take into account that their spending on imports increases entry by foreign producers, hence the mass of imported varieties). Given that countries are symmetric in the current paper, the terms-of-trade incentive for trade intervention is neutralized with reciprocal liberalization. The optimality of free trade concluded above suggests that the markup and entry distortions offset each other exactly, with balanced market size and with reciprocal free trade. This is in contrast with the literature considering unilateral tariff changes, where the entry distortion is typically found to be dominated by the markup distortion starting from free trade, and as a result, a positive import tariff is welfare-improving. Here, with multilateral trade policy coordination, an import subsidy not only increases foreign varieties’ presence in the domestic market, it also increases the entry of local varieties into foreign markets due to more favorable market access reciprocated by foreign countries via an equivalent import subsidy. This amplifies the impact of an import subsidy on industry aggregate productivity, and rivals exactly the incentive for an import tariff to correct the markup distortion, hence the optimality of free trade.

Jørgensen and Schroder (2008) also study the optimal reciprocal trade policy in a setting with heterogeneous firms. However, they model the firm heterogeneity in terms of fixed export cost rather than firm productivities. Firms are identical otherwise. Thus, the dynamic effects of trade policy on the industry aggregate productivity as emphasized here are absent in their framework. Contrary to the current result, they found that the optimal reciprocal import tariff rate is positive. This difference may be explained by the fact that the negative impact of a positive import tariff on the aggregate productivity (and hence on the welfare level) is not taken into account in their framework.

Contrary to multilateral, reciprocal, trade policies, unilateral trade policies are another interesting question. This was studied, for example, by Demidova and Rodríguez-Clare (2009) in a small-economy setting. Because of the small-economy setting, asymmetric economic structures across countries are allowed; however, parametric assumptions have to be imposed to derive their results. In their framework, trade restrictions will not play a symmetric role as here on the importing and the exporting country, since the rest of the world’s expenditure, price level, and cost structure are taken to be fixed. They found that the optimal unilateral policy for a small economy is an import tariff, an export tax, or a consumption subsidy of the same magnitude. This lack of incentives to further lower the import tariff unilaterally to the free trade level may be explained by the lack of extra export revenues (and extra push to the aggregate productivity level) that would be generated if the tariff reduction were reciprocal.

As discussed in the introduction, Bagwell and Lee (2018) find that starting at global free trade, efficiency is enhanced with small import subsidies in the Melitz setup, with Pareto productivity distribution and an additional competitive sector. This finding, contrary to the current paper’s, is likely due to the presence of the competitive sector and the possibility of labor reallocation across sectors. In particular, with the additional sector that is perfectly competitive, the market price of the differentiated goods relative to the competitive good is higher than their relative marginal cost of production, since the former sector’s goods are priced at a markup over marginal cost, in contrast with the latter sector where price is set at marginal cost. Thus, from the social planner’s perspective, the consumption of the differentiated goods, and hence labor allocation to the sector, relative to the competitive sector, is less than optimal without further intervention (from the benchmark of what is called for to address any global inefficiency within the differentiated-good sector, which is shown to be nil in the current paper). An import subsidy in this case lowers the aggregate price of the differentiated-good sector and helps correct this “markup” distortion across sectors.

III. CONCLUSION

As we allow trade restrictions to take on the meaning of trade policy barriers, instead of iceberg trade cost, we see that most of the qualitative effects of trade restrictions on the firm-level variables hold true as they were proposed by Melitz (2003). This similarity probably explains the impressions that trade policy barriers are equivalent to iceberg trade cost. However, we also verify from the above analysis that they are not equivalent in the strength of their trade-restricting effects and of their welfare implications. With import tariffs, welfare includes an extra real tariff revenue component in addition to the real wage component. The variation of welfare with respect to tariff rates can be analyzed by studying the variation of the tariff revenue and the variation of the aggregate price level as the tariff rate changes. Derivations of these comparative statics are complicated by the fact that as the tariff rate varies, the cutoff productivity levels for production and for export and the mass of local and imported varieties all change at the same time, as was the case in Melitz (2003). They are further complicated by the fact that tariff revenues and the aggregate price level are nonlinear in tariff rates in different directions. However, as shown, these derivations are analytically tractable and have sensible economic interpretations. In the end, the conflicting impacts on welfare via these components as the tariff rate varies sum up to a clear-cut result that free trade is the best reciprocal policy.

To conclude, the result of the paper expands the normative support for a free world trading system, from the classical setup of perfect competition to the alternative Melitz (2003) setup with monopolistic competition and firm heterogeneity. Some remarks are in order. The optimality of free trade is derived in this paper with balanced country size and reciprocal trade policy. By allowing for asymmetric country sizes, the efficiency of free trade at the global level likely will continue to hold. However, in this case, large countries benefit less from a reciprocal import subsidy and entry into foreign markets (relative to small countries). The imbalance in welfare concession implies that larger countries are likely to favor import tariffs. As a result, reciprocal trade liberalization likely will stop short of free trade, provided no international transfer mechanism. This might help explain the resistance of developed countries to further multilateral liberalization in the recent decades, with increasingly heterogeneous compositions of GATT/WTO membership and unbalanced concessions.

Tables & Figures

Figure 1.

Relative magnitude of lower cutoff

productivity levels with import tariffs and with iceberg trade cost" />

productivity levels with import tariffs and with iceberg trade cost" />

References

- Bagwell, K. and S. H. Lee. 2018. Trade Policy under Monopolistic Competition with Heterogeneous Firms and Quasi-linear CES Preferences. Manuscript.

- Baldwin, R. 2005. Heterogeneous Firms and Trade: Testable and Untestable Properties of the Melitz Model. NBER Working Paper, no. 11471.

- Baldwin, R. and R. Forslid. 2006. Trade Liberalization with Heterogenous Firms. NBER Working Paper, no. 12192.

-

Demidova, S. and A. Rodríguez-Clare. 2009. “Trade Policy under Firm-Level Heterogeneity in A Small Economy,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 100-112.

-

Felbermayr, G., Jung, B. and M. Larch. 2013. “Optimal Tariffs, Retaliation, and the Welfare Loss from Tariff Wars in the Melitz Model,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 13-25.

-

Gros, D. 1987. “A Note on the Optimal Tariff, Retaliation and the Welfare Loss from Tariff Wars in a Framework with Intra-Industry Trade,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 23, nos. 3-4, pp. 357-367.

-

Haaland, J. I. and A. J. Venables. 2016. “Optimal Trade Policy with Monopolistic Competition and Heterogeneous Firms,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 102, pp. 85-95.

-

Jørgensen, J. G. and P. J. Schröder. 2008. “Fixed Export Cost Heterogeneity, Trade and Welfare,”

European Economic Review , vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 1256-1274.

-

Melitz, M. J. 2003. “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity,”

Econometrica , vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 1695-1725.