- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | The geostrategy of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AFCFTA) and third parties: a focus on China / 2022 / EUREKA: Social and Humanities no.4, pp.43 / |

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 26, No. 1, 2022. pp. 49-91.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2022.26.1.405

Number of citation : 1China’s Public Diplomacy towards Africa: Strategies, Economic Linkages and Implications for Korea’s Ambitions in Africa

|

Kyung Hee University |

Abstract

Recent years have witnessed renewed interest in Africa and public diplomacy has emerged as the vital tool being used to cultivate these relations. China has been leading in pursuing stronger economic partnership with Africa while middle powers such as Korea are also intensifying engagement with the continent. While previous studies have analyzed the implications of China’s activities in Africa on advanced powers, none has examined them from the paradigm of middle powers. This study fills this gap by assessing China’s activities in Africa, their economic engagement and implications for Korea’s interest in Africa. The analysis is qualitative based on secondary data from various sources and literature. The study shows that China’s public diplomacy strategy involves a high degree of innovation and has evolved to encompass new tools and audiences. China has institutionalized a cooperative model that permeates many aspects of governance institutions in Africa, enabling it to strengthen their relations. This could also be helping China to adjust faster leadership transitions in Africa. Whereas the US is still the most influential country in Africa, China is influential in economic policies and has outstripped the US in infrastructure diplomacy. This could be because African policy makers align more with China’s economic model than the US’ mainstream economics. Chinese aid to Africa has been diversified to social sectors that are more responsive to the needs of Africa. Trade and investment relations between China and Africa have deepened, but so does trade imbalance since 2010. China mainly imports natural resources and raw materials from Africa. But this product portfolio is not different from Korea and the US. China’s energetic insertion in Africa using various strategies has significant implications for countries with ambitions in Africa. Korea can achieve its ambitions in Africa by focusing resources in areas it can leverage its core strengths-such as education and vocational training, environmental policy and development cooperation.

JEL Classification: B22, B27, F21

Keywords

China, Africa, Public Diplomacy, Strategies, Economic Linkages, South Korea

I. Introduction

Public diplomacy is the cultivation by governments of public opinion in other countries and involves the means by which a government learns about, understands and influences foreign publics to enhance its national image and international influence (Prabhu and Mohapatra, 2014). It includes communication with foreign officials and the publics, and processes such as negotiations and networking (Kostecky and Narray, 2007). Public diplomacy falls within the realm of foreign policy, and serves a supportive function to major policy initiatives which have economic partnerships, high-political and even military alliance components (Henrikson, 2006). In terms of economic partnerships, public diplomacy is used as a soft power strategy for trade, investment and economic prosperity promotion (Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs, 2016). Economic diplomacy is gradually taking over the traditional politics-oriented diplomacy (Petrovsky, 1998). Economic diplomacy is the use of government recourses to promote the growth of a country’s economy by increasing trade, promoting new investment opportunities and collaboration on bilateral and multilateral trade agreements (Diplo Foundation, 2022), as well as advancing a country’s political and strategic interests (Wayne, 2019). The most common forms of economic diplomacy are foreign aid and economic sanctions (Diplo Foundation, 2022; Wayne, 2019).While using public diplomacy to pursue economic relations is a common trend (Petrovsky, 1998), Nicholas (2020) explains that it is entrenched in countries such as Korea because of its legacy of developmental state, which combines the interest of the state and business. Similarly given China’s state-centric approach, the government links diplomacy with economic interests including helping Chinese businesses to expand abroad (Shullman, 2019).

South Korea (hereafter Korea) and China’s understanding of public diplomacy is relatively new. It was not until 2010 that Korea began to pursue public diplomacy (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Korea [MOFA], n.d.). Korea understands public diplomacy as a means of gaining trust of the international community and increasing its global influence (MOFA, n.d.). This is to be achieved by sharing its history, traditions, culture, arts, values and policies with the world. In the case of China, until the beginning of economic reforms and opening, there was no emphasis on public diplomacy, even though by 1990s it had begun dialogue and exchange information in the area of diplomacy (Mo and Zhou, 2012). With progress of reforms and opening up and its increasing international stature, China became cognizant of the importance of public diplomacy in promoting mutual understanding among countries. China recognizes that its reputation can be the focal point in assessing its intentions amidst its rising capabilities and increased engagement with the world. Furthermore, China embraced public diplomacy to counter the Western narrative, which China sees as an attempt to misinform the foreign publics and distort its image. China wants to be understood as a civilized nation with a rich history, ethnic unity and cultural diversity, and as an oriental power with good governance, developed economy and cultural prosperity (China Daily, 2014). In view of these, China began to carry out all-round public diplomacy in the fields of economy, culture, science and technology (Mo and Zhou, 2012). Today China has shifted from advertising its culture as the primary source of soft power to promoting its model of governance. This underscores China’s presentation of policies such as Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and more recently its approach to COVID-19 as instances of improvements in global governance or as Chinese ‘gifts’ to the world (d’Hooghe, 2021).

Both China and Korea have implemented public diplomacy in Africa. Their interest in Africa have been both economic, such as establishing trade relations, as well as geopolitical, such as alienating their political threats. For instance, China implemented public diplomacy in Africa to seek solidarity against imperial powers and to isolate Taiwan, while Korea implemented public diplomacy in countries that maintained relations with North Korea to isolate the latter (Bone and Kim; 2019; Shinn, 2019). Recent years have witnessed renewed interest in Africa and public diplomacy has been one of the core strategies deployed to cultivate bilateral relations. The renewed focus in Africa, while also underscored by political or strategic goals (Yun and Thornton, 2013), has been heightened by emerging economic opportunities in the continent. According to Gurria (2017), advanced countries’ interest in African is due to its potential based on its young population, fast growing markets, emerging middle class, ample natural resources and diversifying economies. China’s heightened economic diplomacy in Africa has in particular created a new momentum among Africa’s traditional allies that are reinvigorating their diplomacy strategies to strengthen economic cooperation with Africa. Middle power countries such as Korea and India have also revitalized their diplomacy in Africa (Nicholas, 2020; Mol et al., 2021; India’s Ministry of External Affairs, 2018). However, while previous studies have examined implications of China’s engagements with Africa on more advanced powers (Yun and Thornton, 2013; Custer, 2018), none has examined the implications from the paradigm of middle powers. Against this background, this paper seeks to analyze China’s public diplomacy towards Africa and implications for Korea which also has interest in the continent.

1. Theoretical Framework and Research Questions

China and African countries belong to the third world countries: While China is the single largest developing country, Africa is an agglomeration of developing countries. In the Beijing Declaration of 2018, China and African heads of states reaffirmed the notion that China and Africa have always been a community of destiny, based on common historical encounter and a shared goal of development and political aspirations (China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA], n.d.). Since China’s founding, diplomacy towards Africa has occupied an important place in its policy. China has provided aid and concessional loans to Africa, and has vigorously promoted Chinese state-owned enterprises and private companies to invest in Africa. African governments on the other hand have supported China on issues involving its core interests. African countries equally acknowledge Korea as a contemporary in terms of development and colonial experience. Many African leaders express admiration for Korea, find its history of civilization appealing and view it as an archetype for socio-economic and socio-cultural success (Ochieng and Kim, 2019). However, even though Korea-Africa relations date back to the period of independence, it has been juxtaposed with weak economic and diplomatic exchanges. But recently Korea embarked on an ambitious strategy to attain a middle power status. This policy aims to enable Korea take on greater international responsibilities that elevate its status as a competent and responsible stakeholder in the global community (Botto, 2021). President Moon Jae-in’s middle power policies are regional and focused in Asia. However, President Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) envisioned Korea’s identity as a middle power through a global strategy that was being implemented as a global Korea Initiative (Botto, 2021). Therefore, Korea’s middle power ambitions are global and not limited to Southeast Asia. Within Asia, Korea has adopted a policy of balanced diplomacy. This policy is premised on helping Korea to maintain strong relations with US — its longtime ally, while simultaneously maintaining strategic relations with China — another key ally in trade and North Korea security threat. It is not clear how China’s ambitious policy in Africa will play out with Korea, which is equally focused on reinvigorating ties and economic exchanges with Africa. This is because China has conflicting perspective on the rise of middle power. China views the emergence of middle powers as a phenomenon occasioned by the relative decline of the U.S. after the global economic crisis. In this regard, China’s expectation of middle powers has been that they will become cooperative partners in counterbalancing the existing global order led by U.S. (Lee, 2015). However, in fact China has a dual perception of the middle powers: On the one hand, China hopes that middle powers will become partners in establishing a new international order. On the other hand, as its national capability and interests enlarge due to its rapidly growing economy, China harbors concerns about potential competition and conflict, rather than complementarity with middle powers (Lee, 2015). In view of this unclear understanding of how Korea’s ambitions in Africa would be perceived by China, this paper seeks to analyze China’s public diplomacy strategies in Africa and highlight implications for Korea’s presence and activities in the region. Based on descriptive analysis, the research answers following questions: 1) How has China’s public diplomacy strategies in Africa evolved, and how do they impact China Africa relations? 2) What is the pattern of China’s economic linkages with Africa and how does it bear on Africa? 3) What insights can be derived on how Korea implements its strategies in Africa in light of China’s growing ties with Africa? The impact of China’s diplomacy is analyzed from the perspective of China’s objectives as well as Africa’s interest. Data sources include AidData, Resource Trade Earth, Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward FDI and UN Comtrade. The research contributes to the literature on the raging debate on China’s engagement with Africa and comprehensively examines the different modes of China’s diplomacy in the continent. Moreover, while previous studies may have examined implications of China’s engagements with Africa on more advanced powers, none has examined them from the paradigm of middle powers such as Korea.

2. Actors in China’s Public Diplomacy

The actors in China’s public diplomacy can be ‘classified’ into state and non-state actors. The state plays the main role in planning and executing public diplomacy strategies. Non-state actors include the business community and the emerging civil society organizations. This group compliments the state’s soft power strategies, but they are not fully autonomous from the state, and thus less ‘non-state’ than the term would suggest. Considering this blurred distinction between the ‘state’ and ‘non-state’, it would be inappropriate to categorize China’s actors. Nevertheless, in spite of the lack of autonomy from the state, the ‘non-state’ actors with the Chinese characteristics can be distinguished in three ways: majority of them, especially the newly established NGOs are: (1) not initiated by the state; (2) not operated by the state; and (3) aim to achieve their own societal and commercial interests (d’Hooghe, 2007). The case of Korea presents a different scenario: the actors are clearly identifiable into three groups: the state, the local government and the private sector (Choi, 2019). The state performs the role of the chief actor, whereas the local governments, the private sector and NGOs are ‘cooperative actors’ and play the role of influencing the state’s policies. The personal pursuits of citizens, private corporations, NGOs and the media are a significant outlet of Korea’s public diplomacy. Moreover, Korea’s public diplomacy includes ‘citizen diplomats’ who are MOFA’s social media followers and program participants (Krasnyak, 2017). These actors are deemed non-state actors, and the role of the state is to make them knowledgeable, concerned and appreciative of the value of public diplomacy. In this regard, one goal of Korea’s public diplomacy is to promote public-private partnerships (MOFA, n.d.). China’s public diplomacy can be characterized as state-centered diplomacy, which is equated with ‘vertical diplomacy’, that is ‘government-to-people’ contact (Liu, 2018). Korea’s public diplomacy on the other hand can be characterized as ‘horizontal diplomacy’ because the activities of the private actors and the government are inextricably linked. ‘Horizontal public diplomacy’ consists of multiple actors characterized by communication and cooperation (Wei, 2020).

II. Evolution of China’s Public Diplomacy in Africa

China’s public diplomacy towards Africa serves its strategy to rectify the perceived asymmetrical relations with Africa (Kim, 2020). This perceived asymmetry gives rise to distrust and dissatisfaction towards China ? such as accusations of exploiting Africa. China’s public diplomacy towards Africa thus puts emphasis on establishing a sense of mutual solidarity to evoke the sense of connectedness and shared identity with Africa (Kim, 2018). The development of China’s public diplomacy towards Africa began with acknowledging the mutual needs of China and Africa. These relationships have however been defined primarily by the global environment, political and economic developments in China, and to a little extent Africa’s domestic circumstances. Moreover, the phases of its diplomacy are closely linked with the changes in China’s leadership. According to d’Hooghe (2007), the most important factor that has shaped China’s diplomacy is its economic rise that has enabled it to assert itself as a global player. This economic rise has nonetheless also been interpreted as a threat by many countries. Political developments, such as gradual increase in personal freedoms, openness and civil consciousness have facilitated the emergence of ‘non-state’ actors in China’s diplomacy. The second factor fueling China’s diplomacy is the rapid development of its foreign policy. The development of China’s foreign policy has been in tandem with its economic modernization: China needs a stable and peaceful international environment to sustain its economic growth (d’Hooghe, 2007). As a result, it is escalating its efforts to avoid conflicts and dependency on one country or region.

The first phase in the development of China-Africa relation began in 1949 to 1976. This period coincides with the rise Mao Zedong to become the Chinese Communist leader. The early years did not witness a serious outreach to Africa as Mao focused on consolidating his rule (Shinn, 2019). From 1949 to early 1990s, China focused more intensely on establishing political relationship with Africa rather than economic relationship. In this period, China struggled economically and could hardly offer significant economic assistance. Thus, the 1955 Bandung Afro-Asian conference can be seen as the first significant outreach in China-Africa relations (Chen, 2017). China used the conference to press upon African delegation to adopt its five principles equality, mutual benefit and mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty. The principles remain vital to its foreign policy and its diplomacy policy is anchored on them. China sought support from developing countries, mainly in Africa, in order to break the isolation and economic blockade of the West during Cold War (Large, 2008). The wave of independence of African countries also elicited China’s response: China’s diplomacy was based on ideological and military solidarity with African states struggling for liberation. This solidarity enabled China to cement its anti-colonial and anti-imperialist credentials (Alden and Alves, 2009). It focused on African states that aligned with its ideology and supported their liberation movement (Shinn, 2019). Public diplomacy was realized by means of education, cultural exchanges and aid to Africa. From 1960s through to 1970s, China provided financial aid, technological assistance, medical support and scholarship opportunities for Africans to study in China (Alden and Alves, 2009). By 1976, a total of 144 African students had gone to study in China (Anshan, 2018), while 14 Chinese teachers had taught in Africa by the end of 1966 (Mao, 1965). However, from 1967 to 1977, China's public diplomacy towards Africa lost the momentum due to the influence of Cultural Revolution. China-Africa relations became ideologically driven and the promotion of the socialist revolution in Africa obstructed smooth flow diplomacy. This period recorded a considerable decline in high-level visits by African government officials to China and senior Chinese government officials to Africa (Barnouin and Yu, 1998). Nonetheless, Chinese aid to Africa did not slow down. By the end of 1970s, China had provided assistance to 39 African states amounting to about $ 2.4 billion in interest-free loans (Shinn, 2019). There was also a significant decline in education and cultural exchanges, and sports gained prominence in China’s diplomacy. China revitalized diplomatic ties with Africa in early 1970s and it culminated with its ascension to the United Nations in 1971 with the support of African states.

The second phase of China-Africa relations took off in 1978 and lasted until 1992. China ushered in a new era of Reform and Opening up with the rise of Deng Xiaoping as Chinese paramount leader. At the same time, structural adjustment programs (SAPs) in Africa throughout the 1980s failed to stimulate economic transformation. Against this backdrop, China launched its economic-led policy toward Africa, and economic assistance became the central pillar of its engagement with Africa. Even though in 1980s China maintained close ties with Africa, aid and trade stalled, while direct investment did not constitute a significant part of their relations (Shinn, 2019). This was in part because China focused more intensely on its internal economic transformation, thus had fewer resources to devote to other countries. Secondly, Africa countries failed to open up to global trade, further obstructing relations in the economic front. This period was equally characterized by few high profile visits to Africa. In addition, 1980s marked the period China adopted a new foreign policy to govern its relations with the rest of the world, and particularly with Africa. From 1969, China had frosty relations with African countries perceived as close allies of Russia, one of its power rivals. The contours changed when China adopted a policy of peace and ‘non-contested relations’ abroad. This policy came to bear when Chinese prime minister visited Africa in 1982 and declared an era of equality and mutually beneficial cooperation with Africa (Yan, 1988). The number of African countries that recognized China subsequently grew from forty-four in 1970s to forty-eight in 1980s, and fifty-five African presidents visited China between 1981 and 1989 (Shinn, 2019). Consequently, economic aid to Africa steadily increased, while education and cultural exchanges were rejuvenated.

The year 1993 to 2002 when Jiang Zemin took over the Chinese leadership marked the era of intensification and institutionalization of China-Africa relations. As Chinese companies began to internationalize after 1998, Africa became a strategic focus for Chinese outward-bound corporations especially in the extractive industries. This gave Africa renewed sense of importance (Davis et al., 2008). One discernible feature of this phase of China’s diplomacy was the increase in high profile visits to Africa (Shinn, 2019). China also continued with its crusade for mutually beneficial relationship, respect for sovereignty, cooperation on international fora and equal treatment of partner countries. In 2000, China’s public diplomacy towards Africa entered a critical stage of institutional construction. While maintaining the normative exchanges of public diplomacy, China also conceptualized the institutional construction of their relations, birthing China-Africa Cooperation Forums (FOCAC) as a dialogue platform (Davies et al., 2008). FOCAC became the vehicle for coordinating Chinese policy toward Africa, with the first FOCAC meeting held in Beijing in October 2000. During this period, it became a common practice for foreign ministers to visit Africa in their first overseas assignments (Taylor, 1998). Similarly, China’s notion of aid to Africa changed significantly: China began to pay more attention to the uniqueness of African society and changed its emphasis on economy from 1990s to the development of human welfare and society. As a result, social development assistance became part of the pillars driving China’s public diplomacy towards Africa. Its diplomacy also expanded in educational and cultural exchanges with the launch of the ‘African human resources development fund’ and the ‘Confucius Institute’s Chinese-African teaching program in 2006.

The year 2002 to 2012 is a continuation of the preceding phase of China’s public diplomacy strategies, but also marks a distinct phases of China-Africa relations. Hu Jintao rose to the position of secretary general of Chinese Communist Party (CPC) in 2002 and became president in 2003. Hu Jintao inherited a robust relationship between China and Africa. At the time of his ascension to power, four African countries still maintained diplomatic ties with Taiwan, but by the time he was relinquishing office, almost all African countries had severed ties with Taiwan, signaling a significant triumph for China’s ‘One China Policy’ (Shinn, 2019). Hu Jintao was the brainchild behind China’s philosophy of ‘Peaceful rise’ and ‘Harmonious world’. These thematic areas were conceived to counter the fears that China’s rise was a threat to the world (d’Hooghe, 2007). China’s economic interest at the time underscored its diplomacy and the two concepts assumed that China’s interest could only be realized in a peaceful global environment. This phase thus witnessed a deepening economic linkages between China and Africa. China increased its dependence on Africa’s raw materials to drive its economic growth objectives. Similarly, China escalated its soft power strategy towards Africa, evidenced by increase in scholarships to African students, Confucius Institutes and Chinese media outlets in Africa (Shinn and Eisenman, 2012). It was during this phase that the second FOCAC ministerial conference was held in Ethiopia, the first such meeting held outside China (MFA, n.d.).

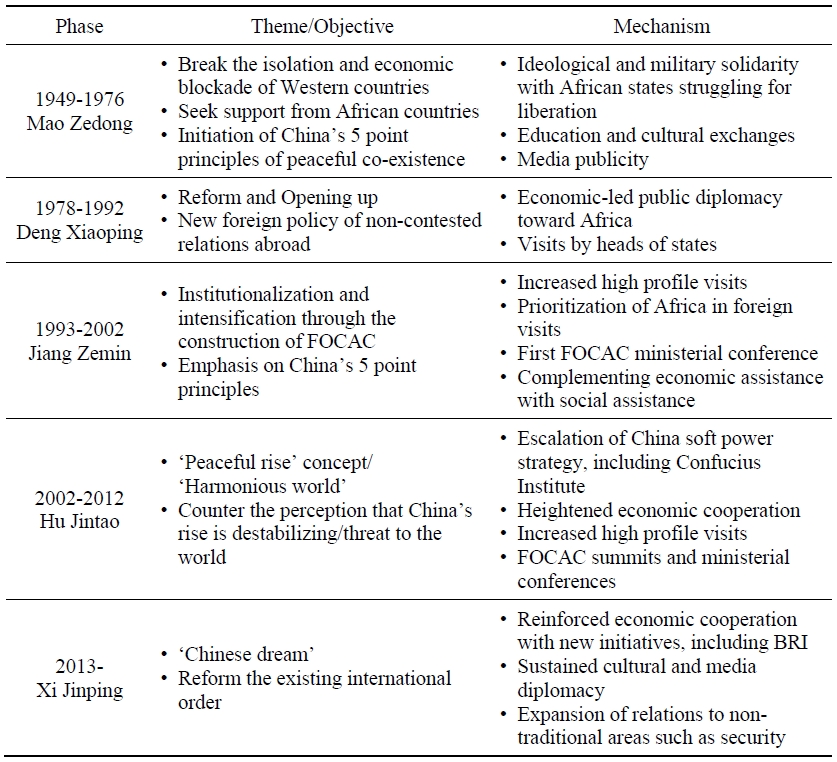

The current phase of China-Africa public diplomacy took off in 2012 when Xi Jinping became the secretary general of CPC and president in 2013. This phase can be characterized as ‘China’s energetic insertion’ in the globe. China’s strategic objective has been to reform the existing international order in a manner that can better serve its interests. This goal is consistent with the ‘Chinese dream’ conceived under president Xi. It is in this area that China hopes to form a cooperative alliance with middle powers such as Korea. In relation to Africa, China’s public diplomacy in the context of ‘Chinese dream’ links the development of Africa with that of China. At the core of achieving this new order is the Belt and Road Initiative, which is Xi’s signature project that includes Africa. While many new initiatives such as this exist, China has maintained elements of the previous phases of its diplomacy, such as high-ranking Chinese officials visiting Africa as a priority. Cultural and media diplomacy have also gained prominence in China’s soft power diplomacy (Hu et al. 2018) (See Table 1). Unlike China, Korea’s diplomacy towards Africa has been characterized by slow growth, lack of continuity as well as long-term orientation (Felicia, 2016). Park (2019) affirms that throughout 1970s and 1980s, Korea-Africa relations have gone through cycles of stagnation, inconsistencies, weak diplomatic exchanges and revitalization. For instance, there were very limited high-level contacts between Korea and Africa for the five decades following the Korean War, a period that witnessed only one visit to Africa by a Korean president. President Chun Doo-hwan was the first to visit Africa in 1982 (Monareng, 2016), and it was until 2006 that President Roh Moo-hyun made the second visit to Africa (Bone and Kim, 2019). One drawback in Korea’s public diplomacy in Africa is that it changes almost every five years with the election of a new president, thereby disrupting the flow of their relationships.

III. Assessing China’s Public Diplomacy Activities in Africa

1. Official Development Assistance (ODA)

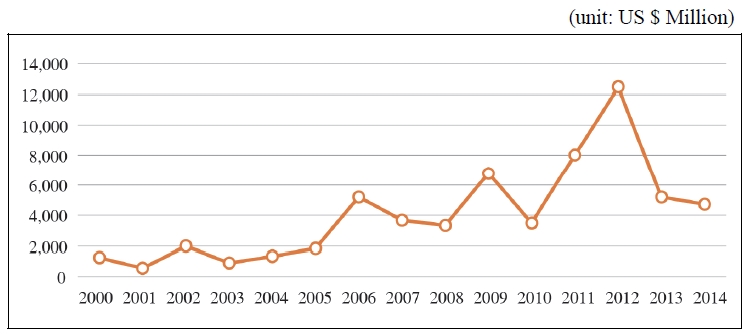

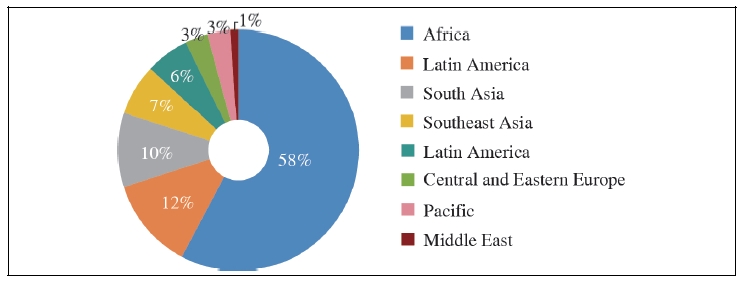

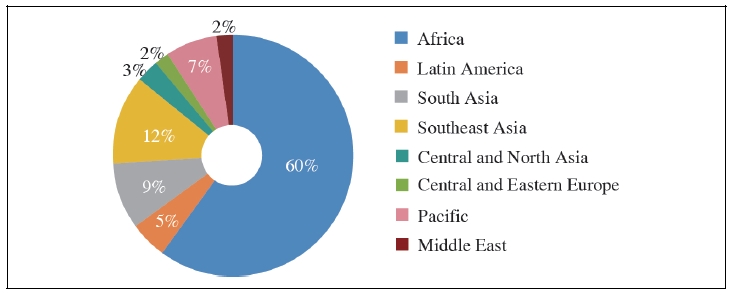

Official development assistance has been a vital instrument in China’s public diplomacy in Africa. Primarily, China uses its ODA to mitigate crisis in Africa and to support various developmental projects ranging from health care, education, agriculture, humanitarian assistance and other aspects focusing on the most vulnerable groups, such as children, women and the youth. This aid is provided as complete projects, goods and materials, technical cooperation, human resource development cooperation, Chinese medical teams working abroad, emergency humanitarian aid, volunteers to foreign countries and debt relief.1 Complete projects constitutes a major form of Chinese aid to Africa. Complete projects refer to productive or civil projects constructed in recipient countries and financed through grants or interest-free loans.2 The projects include roads, railways, ports, bridges, stadia and urban transport . Given the large size of its financing compared to a country like Korea, these projects stand visible in many parts of Africa and thus gives China unmatched publicity and presence in the continent. For example, China constructed the African Union headquarters, which is the tallest building in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The Chinese approach focusing on infrastructure is particularly aligned with the needs of Africa since most countries in Africa have poor infrastructure, which has been a major impediment to the development of the region. Health is another critical area of Chinese aid that meets the needs of Africa. As a region that has been plagued by diseases, Chinese aid in the health sector, which includes medical technology and medical personnel is a positive contribution the continent. In the area of agriculture, in order to support African countries through food crisis, China provides food aid to affected countries. In 2011, China sent $67 million food aid to northeast Africa. The productivity of African farmers has been enhanced through the construction of modern agricultural technology demonstration centers, agricultural management and technical training. From 2000 to 2014, China’s ODA to Africa has been on an upward trajectory, even though with fluctuations (see Figure 1). Geographically, in terms of total official financing, including non-ODA-like finance, between 2000 and 2014 Africa accounted for 34% of Chinese financing, Central and Eastern Europe 16%, Latin America 15%, South Asia 14% Southeast Asia 11%, while other regions each received less than 10%. In terms of ODA finance, Africa accounted for about 58% of China’s ODA to developing countries. This is followed by Latin America 12% and South Asia 10% (see Figure 2). In terms of projects financing, Africa represents 60% of all Chinese projects to developing regions, followed by Southeast Asia 12% and South Asia 9%. China’s projects to other regions account for a very small share of its number of projects (see Figure 3). According to OECD statistics, Korea’s ODA is still mainly concentrated in Southeast Asia. However, since 2006 its ODA to Africa has increased consistently from $47.83 million (2006) to $408.01 million (2017). This is compared to its ODA to Southeast Asia which was $75.85 million (2006) and $478.63 million (2017).3 Korea’s sectors of assistance mirrors those of China and includes infrastructure, education and health. A fundamental weakness is that Korea’s ODA is disintegrated between different ministries implementing ODA and grant projects as stand-alone projects. This diminishes its effectiveness because due to the small size of its aid, standalone projects do not gain much visibility. It is also difficult to accumulate experiences due to lack of follow up (Kim, 2017).

China’s aid involves a significant degree of innovation, which helps it to remain relevant to the changing global circumstances. The latest instance is the covid-19 global health crisis. China was the first country offer bilateral assistance to Africa in March 2020, which later became Covid-19 diplomacy. Since then, an array of actors have been involved in providing medical supplies to help Africa contain the crisis. These include the Chinese SOEs, Chinese private corporations and Chinese nationals in Africa, and their efforts have been coordinated by the Chinese embassies in Africa (Bone and Cinotto, 2020). Providing vaccines to Africa was vital as WHO expressed concerns that vaccine nationalism was hampering developing countries from getting enough supply and obscuring the efforts to contain the pandemic. China also joined the Covax - an alliance of developing countries mostly from Africa that championed the distribution of Covid-19 to help vaccinate the most vulnerable population. Covid-19 crisis caused serious economic deterioration and fiscal restraint, thereby raising the possibility of debt default. China is the largest lender to sub-Saharan Africa, having lent $64 billion versus the World Bank’s $62 billion. In order to ameliorate the economic effects of covid-19, China restructured debt repayment to Africa, including cancellation of interest-free loans.

2. Exchange Diplomacy

Exchange diplomacy takes two common forms namely, educational exchanges and cultural exchanges (Bettie, 2020). Unlike propaganda that involves manipulation of information to achieve the desired objective, exchanges open up the space for dialogue and exchange of alternative worldviews to create mutual understanding (Scott-Smith, 2009). Open communication at the grassroots creates meaningful relationships and trust. Exchanges involving study abroad programs can play a crucial role in economic linkages. According to cross-cultural theory of migrant-indigene relations, migrants serve as a link, a contact and a bridge connecting their country of origin with their place of domicile (Bodomo, 2014). Migrants may increase trade relations due to their preferences for goods produced in the country where they last resided. Additionally, by virtue of links to their home countries and knowledge of their host economies, they are able to scan opportunities for trade between the countries (Gould, 1994). At the beginning of reform and opening up, China and African signed bilateral cultural cooperation agreements to enhance cultural exchanges. In the area of educational exchanges, China established the African human resources development fund in 2000, which led to expansion of educational cooperation and exchanges (Xi, 2015). One of the thematic areas of FOCAC triennial meetings is educational exchanges and training (Bodomo, 2014). In the FOCAC 2006 meeting, China committed to:

• Increase the number of Chinese government scholarships to African students from the current 2,000 per year to 4,000 per year by 2009;

• Provide annual training for a number of educational officials as well as heads and leading teachers of universities, primary, secondary and vocational schools in Africa;

• Establish Confucius Institutes in Africa to meet their needs in teaching the Chinese language and encourage the teaching of African languages in relevant Chinese universities and colleges.4

The commitments to enhance China-Africa exchanges have been reaffirmed in the subsequent FOCAC meetings. During the 2009 FOCAC meeting, China further declared with respect to education exchanges to:

• Help African countries build 50 China-Africa friendship schools in the next three years;

• Implement the 20+20 Cooperation Plan for Chinese and African Institutions of Higher Education to establish a new type of one-to-one inter-institutional cooperation model between 20 Chinese universities (or vocational colleges) and 20 African universities (or vocational colleges).

• Continuously raise the number of Chinese governmental scholarships to Africans, and increase the number of scholarships to Africans to 5,500 by 2012.

• Continue promoting the development of Confucius institutes in Africa, increase the number of scholarships offered to Chinese language teachers to study in China and double the efforts to raise capacity of native African teachers to teach Chinese language.5

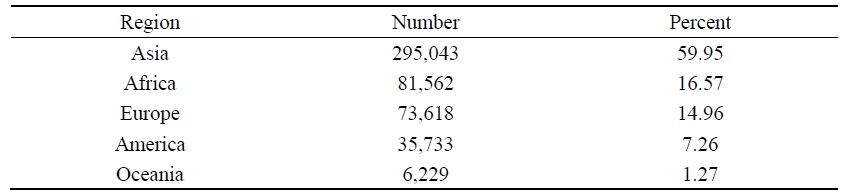

The commitments have led to a noticeable presence of African students in Chinese universities. According to statistics from China’s Ministry of Education, there were 492,185 international students from 196 territories studying in China in 2018. Out of these, 59.95% were from Asia, while Africa accounted for the second largest proportion with 16.6% (see Table 2). According to United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2020), China is the largest single provider of university scholarships to students from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), providing over 12,000 out of 30,000 scholarships that were awarded by the top 50 global donors. This implies China accounts for 40% of the total scholarships awarded to SSA annually. The China-Africa think tank exchange forum has also been operationalized as a ‘two-track diplomacy’ and enables scholars from China and Africa blend their strategic thinking through joint conferences and research projects deemed to be of strategic imperative to both sides (Yun, 2015).

In the area of cultural exchanges, China has put greater emphasis on Confucius institutes (CIs). The aim is to enhance understanding of Chinese language and culture. The logic underpinning this strategy is that through familiarity with each other’s language, China and Africa are able to cultivate sustainable and deeper economic linkages. China established the CI in 2004 and it is arguably the largest language and culture promotion Institute in the world (King, 2014). The success of CIs is varied across the world; while in Western countries it has been associated with China’s ideological or propaganda campaigns, in Africa CIs remains robust in many countries. CIs in Africa are demand-driven and takes the form of a joint venture. This means that foreign education institutions apply for its establishment and contributes financially towards its operations. This encourages a network-based diplomacy in which foreign institutions take an active part in unlocking China’s culture to the world. CIs are strategically located in Africa’s high achieving Universities where they are able to generate greater visibility and draw attention of the locals. To illustrate the weight China assigns the CIs, in 2007, there were only 6 CIs in Africa (d’Hooghe, 2007). By December 2020, 45 out of 54 African countries were hosts to 61 CIs (Li, 2021), and none has been closed (Li, 2021). In addition to teaching Chinese language and culture, CIs have been instrumental in training Africans, incorporating them in various forms of Chinese presence in Africa and helping them connect their own development trajectory with the successful emergence Chinese economy. In this sense, CIs are part of China’s broader strategy to export not only its own culture and language, but also to diffuse its development model as a template for Africa. Some African CI students acknowledge that it has opened opportunities for them beyond their countries (Li, 2021). Some Kenyan Universities have officially incorporated Chinese language as a major, a place that was previously reserved only for English and French. In sum, education and cultural exchange programs are poised to strengthen China-Africa socio-economic linkages in the longer term. Bodomo (2010) found that African traders in China, many of whom initially went to China as students are acting as bridges-mediating agents between China and Africa. To play this mediating role, migrant students need to be well integrated into the host country community rather than isolated, because integration allows them to be educated in diverse aspects of the society. Korea is increasingly investing in cultural and people-to-people exchanges with Africa. In the area of cultural exchanges, it has taken cue from China and is operating Korea Studies Centers in selected African countries. The center aims to advance research in Korean language, culture and society and provide training on doing business between Korea and Africa.6 Research shows that Africans who have been exposed to Korean culture tend to have a positive attitude towards Korea and are inclined to buy products with the brand ‘made in Korea’ (Ochieng and Kim, 2019). This implies that culture could be an important soft power tool for advancing Korea-Africa relations. Nonetheless, Korea has not invested significantly in the Korean Studies Center and they are only available in a few African countries. In education, the Global Korean Scholarship (GKS) is an initiative that gives opportunities to Africans to study in Korea. GKS aligns with the interests of MOFA in strengthening Korea’s ODA policy (Ayhan, 2016).

3. High-profile Visits and Party-to-party Exchanges

High profile visits fit within realm exchange diplomacy, but they are distinct in the sense that they are more formal and short term. Whereas countries engage with each other at various levels, the most salient foreign policy decisions are typically made at the highest political levels (China Power Team, 2021). Overseas visits by high ranking officials provide unique insights into foreign policy priorities and the conduct of diplomacy. They are opportunities for officials to shape bilateral and multilateral relationships to their country’s advantage (China Power Team, 2021). The visits provide a platform for dialogue between partners and create space upon which other forms of diplomacy thrive. CPC has developed various forms of exchanges with political parties of African countries (MFA, n.d.). The goal of such exchanges is to enhance understanding and friendship, build trust and amplify cooperation. CPC links to African political parties is rooted in the liberation movement in Africa during which CPC supported African political parties championing independence. For instance, China’s support to South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) and South African Communist Party (SACP) established the foundation for their continuing relations (Alden and Wu, 2014). Today some African political parties benchmark CPC governance mechanisms as a way to create stable political parties. In 2016, Kenya’s ruling Jubilee party officials visited China for training on how to run the party. CPC officials offered training on Party organization, resource mobilization and capacity building on running the party (Benjamin, 2016). While these party-to-party exchanges encourage networking and escalate cooperation, it is noteworthy that CPC is run on an ideological platform that shrinks democratic governance. Entrenching CPC political ideology in Africa’s ruling parties could therefore muzzle political freedom under the guise of stability.

High-level visits encompass Chinese presidential or ministerial level visits to Africa and vice versa. These delegations facilitate continuous communication and cultivate dialogue on issues that intersect both parties’ interests in order to deepen cooperation. To underscore the centrality of this instrument in China’s diplomacy, it has become a tradition for the newly appointed Chinese foreign ministers to visit Africa in their first overseas engagements (Taylor, 1998). Similarly, when Xi Jinping became President in 2013, he visited Congo Brazzaville, Tanzania and South Africa in his first overseas visit after a stop in Russia (Mu, 2013). When he was appointed president for the second term, his first foreign visit was a four-nation tour of Senegal, Rwanda, South Africa and Mauritius in 2018. Interestingly, during this visit, President Xi sought not only to strengthen economic cooperation, but to compliment it with military engagement (Crabtree, 2018), signaling a shift in China’s foreign policy engagement with Africa. This was further demonstrated in 2018 when China hosted the first ever China-Africa defense and security forum, attended by a delegation of high-ranking military officials from 50 African countries, 15 defense ministers and African Union representatives (Xu, 2019). Besides African delegations to Beijing, China sends military personnel for joint training exercises with their African counterparts, and has set up its first military base in Djibouti (Chandran, 2018). While security exchanges is a new dimension of China Africa cooperation, it is consistent with its belief that a peaceful international environment is essential to its economic prosperity. In this regard, China’s military exchanges with Africa can be interpreted as a strategy aimed at protecting its own national assets given its heavy investment in Africa, as well as a strategy to gain greater geopolitical influence. Indeed, Africa’s security environment is a barometer of the global security governance system. Cooperation in this area is essential to combating global terrorism, drug trafficking and piracy in Indian Ocean trade routes. At the same time, it ensures stability needed to spur economic growth of Africa. Between 2007 and 2017 Chinese senior leaders- the president, the premier and foreign ministers made 79 foreign visits to 43 African countries (Lijadu, 2018). Empirical studies have found as much as 40% increase in China’s exports to Africa associated with Chinese prime minister’s visit to a particular Africa country (Denny, 2012). On the other hand, a visit by African trade minister is associated with a near doubling of African exports to China. Korea has had very inconsistent high-level exchanges with Africa. However, recently the trend has changed drastically especially after the launch of ‘Korea Initiative for Africa’s Development’ in 2006. After President Roh Moo-hyun’s visit in 2006, President Lee Myung-bak made another visit in 2011 (Kwon, 2011) and President Park Geun-hye in 2016 (Tankou, 2016). Business executives who simultaneously meet their African counterparts to discuss areas of partnership have accompanied the recent high-profile visits to Africa, implying that the visits are linked with promoting economic ties. President Moon Jae-in has not visited Africa, but the prime minister and foreign minister have visited different African countries. President Moon’s government has also hosted ‘Seoul dialogue’ on Africa and Korea-Africa youth forum, both of which are focused on youth, entrepreneurship and technology.

4. Media Diplomacy

The media plays a profound role in communicating the values, culture and the overall image of a society. Over the years, Western media has dominated the foreign mediascape in Africa. Media diplomacy is a recent development in China’s public diplomacy, and a late entrant in the African mediascape. Today the Chinese media engagement in Africa serves as a central pillar of its contemporary diplomacy. Chinese media entry in Africa was fueled by the realization that the Chinese story was being told through third party voices who could not take responsibility to convey China’s perspective (Latham, 2009). China is also alive to the changing global dynamics occasioned by the information age that has necessitated the need for active direct communication. The rapidly evolving landscape of digital technology in Africa, coupled with its youthful and technology savvy population also provides Chinese media the room to grow. Moreover, there had been a gap between public perception and China’s rapidly developing economic relations and regular contact with policymakers (Wu, 2016). This means that there was less public engagement in China-Africa relations. For a long time China pursued a top-bottom diplomatic approach that placed priority on cultivating relations with African governments, and then working it back to local communities (Ochieng and Kim, 2019). This approach was oblivious to public perception of Chinese image in the continent. The primary objective of China’s media diplomacy is therefore to drive its own narrative among the African audience. China’s intentions in Africa makes this paradigm shift in its diplomacy even more vital: China is not only interested in doing export business with Africa, but also to help Chinese enterprises to enter and successfully operate in the African market. In this regard, China takes cue from Indian diplomacy in Africa: India implemented on a bottom-up diplomacy which focused on establishing relationship with communities-the public, then working it up the scales of the society. As a result, Indian enterprises have been successfully naturalized in Africa and are perceived as though native enterprises.

China’s media diplomacy in Africa has evolved to include a multifaceted approach. Between 2000 and 2006, China’s direct media involvement in Africa’s media industry was in the form of assisting with the media infrastructure: For instance, in 2000, China donated satellite equipment for a television station in Uganda; in 2004, it assisted Gabon to build its national broadcasting station (Wu, 2012). Due to the increasing centrality of media in China-Africa relations, Chinese media operations in Africa has been consolidated within the FOCAC framework of cooperation. During the 2006 FOCAC Beijing summit, China authored the African Policy document outlining the imperative of media cooperation as follows:

“China wishes to encourage multi-tiered and multi-formed exchanges and cooperation between the media on both sides to enhance mutual understanding and enable objective and balanced media coverage of each other. It will facilitate the communication and contacts between relevant government departments for the purpose of sharing experiences on ways to handle the relations with media both domestic and foreign, and guiding and facilitating media exchanges”.7

Subsequently, China has heavily invested in its own media in Africa, with state-owned media agencies present in around 28 countries (Siu, 2019). Since 2012, China has been reporting to and covering Africa through China Radio International, Xinhua, China Global Television Network (CGTV) and China Daily’s Africa Edition, all state-owned media agencies. CGTN opened its continental headquarters in Nairobi Kenya in 2012 and currently reports in six UN languages across Africa. China state-backed investors have also bought shares in African media companies, including South Africa’s Independent Media. This has helped China to gain influence in the local media landscape. Currently, Xinhua has one of the largest correspondent networks in Africa, outmatching other international broadcasters on grassroots journalism (Mwakideu, 2021). There has also been increased interaction between Chinese and African local media professionals including training, which creates room for covering each other’s perspectives. The media cooperation extends to the Africa film industry: China-Africa international film festival- a shared festival was launched in 2007 to create a new China-Africa narrative. The emphasis on objective reporting has not only been crucial to China but also to Africa. Africa has been concerned that the Western media coverage of the continent is negative and stereotypical, portraying Africa as a continent plagued with disease, death and destruction (Marsh, 2016). On the other hand, the Chinese media reports African news in a manner that presents a more positive image of the continent to the world. This reporting thus helps to change the stereotypical portrayal of Africa by the Western media. A study by Wasserman and Madrid-Morales (2018) among communication students in South Africa and Kenya found that some students have news values that overlap with the Chinese media. This may imply compatibility between the journalistic practice of Chinese media in Africa and that of Kenya and South Africa’s future media professionals. In addition, Chinese diplomats or delegations are increasingly open to addressing press conferences during their foreign visits to Africa to highlight China’s role in the continent. Perhaps one of the weakest links in Korea’s diplomacy is the lack of its media footprint in Africa to drive Korea-Africa narrative. Korea culture has only sporadically spread in Africa through local media channels. In Kenya, Good News Broadcasting System (GBS) was the first channel to dedicate a slot to air all popular K-dramas. iTV -Tanzania’s most watched channel, also initiated a Korean drama in the country in collaboration with MBC. Ghanaian channel TV3 and TV Africa, Zimbabwe’s national broadcaster ZBC TV and Nigeria’s AIT are also examples in this regard.8 This coverage is nonetheless limited to showing Korean drama.

5. China-Africa Cooperation Forum (FOCAC)

FOCAC is an institutionalized mechanism of China’s public diplomacy towards Africa; a multilateral mechanism exchange platform exclusive to China and Africa, and plays an extraordinary role in China-Africa relations. It creates a platform for articulating common interests between China and Africa (Mulaku, 2020). By providing a platform for collective dialogue, FOCAC is arguably an effective mechanism for promoting practical cooperation and setting the agenda for constructive interactions. Since its launch in 2000, it has become the engine behind China's diplomacy in Africa, and has birthed a series of new modes of engagement. The African human resources development fund, African cultural personages’ visit to China, the CI in Africa, China-Africa Joint Research and exchanges and China-Africa media cooperation are all anchored within the FOCAC framework. FOCAC deliberations have brought African and Chinese leaders closer together and constructed a shared vision for policy coordination, expanded commercial exchanges and common development (Shelton and Paruk, 2008). As such, it acts a path to intensify the flow of diplomacy resources to Africa, and an example of constructive South-South cooperation and how win-win outcomes can be realized through enhanced dialogue and constructive multilateral interaction (Shelton, 2016).

FOCAC operates various decision-making organs, namely, summits, ministerial conferences and follow up meetings (MFA-FOCAC). Since its launch, China and Africa have held three Beijing Summits and six ministerial conferences. It has also formulated a series of important programmatic cooperation documents and promoted measures to support Africa’s economic development and deepen China-Africa relations. Through the FOCAC dialogue mechanism, China has cancelled Africa’s debt, expanded market access and provided new opportunities for engagement (Shelton and Paruk, 2008). China uses FOCAC meetings to commit to new modalities of partnership. The third and largest FOCAC meeting was attended by 1,700 delegates from China and Africa in Beijing in 2006. The meeting initiated China’s new strategic partnership with Africa and confirmed China’s growing influence in the continent. In 2015, China committed to provide a $60bn package in aid, subsidized lending and state-backed investment, its largest commitment of the conference series. At the 2018 FOCAC, the BRI was introduced as a platform whose development agenda aligns both with FOCAC and African Union’s Agenda 2063 (Benabdallah, 2021). However, in spite of the fact that FOCAC is a multilateral one-country-to-one-continent forum, individual African countries compete one another to win the BRI projects. This implies that if the BRI loans to Africa will decrease in the future, as is likely the case, competition might heighten between African countries to secure the infrastructure and other investment projects. However, the forum has enhanced communication and cooperation between China and Africa and jointly safeguarded their common interests. Overall, China has developed and institutionalized a comprehensive dialogue mechanism that permeates many aspects of governing institutions of African governments. This elaborate cooperation mechanism enables China and Africa to engage more closely and continuously. Korea-Africa Forum can be interpreted as Korea’s attempt to institutionalize relations with Africa and has added impetus to their engagement through dialogue and communication. The forum was birthed as a follow up to ‘Korea Initiative for Africa’s development’ (MOFA, n.d.). The forum identified cooperation in the areas of economy, development and peace and security (MOFA, 2016). Since the launch, Korean people, business executives and students have shown increased interest in Africa (Song, 2007). Nevertheless, the Forum has not significantly changed their discourse. For instance, even though the forum was birthed almost at the same time as FOCAC, it has been slow in growth. This could be partly because Korea is still vigorously focused on Southeast Asia — the ASEAN — and has fewer resources compared to China.

1)The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2011.

2)Ibid.

3)OECD,

4)

5)

6)

7)

8)

IV. Stylized facts on China-Africa Economic Relations

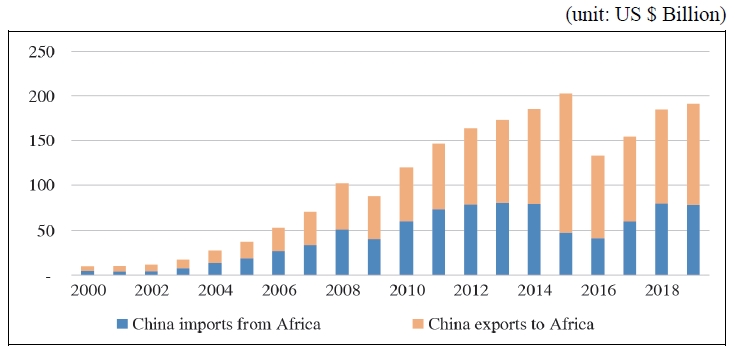

China and Africa have recorded deepening economic linkages. Bilateral trade and investment relations between China and Africa have recorded tremendous growth since China began to intensify its public diplomacy towards Africa. Until 1992 when China just began to escalate its public diplomacy towards Africa, China’s exports to Africa was $1.26 billion, while Africa’s imports to China amounted to only $ 0.49 billion. Between 1992 and 1999 before the launch of FOCAC, China’s exports to Africa increased to $3.2 billion, an increase of 154%. Africa’s imports to China in the same period rose to $1.51 billion, representing an increase of 222%. After the launch of FOCAC, China’s exports to Africa increased from $ 5.01 billion (2000) to $112.72 billion (2019). Similarly, Africa’s imports to China have drastically increased from $4.85 billion (2000) to $78.68 billion (2019) (see Figure 4). However, with these deepening trade linkages, trade imbalance has also heightened in favor of China since 2010.

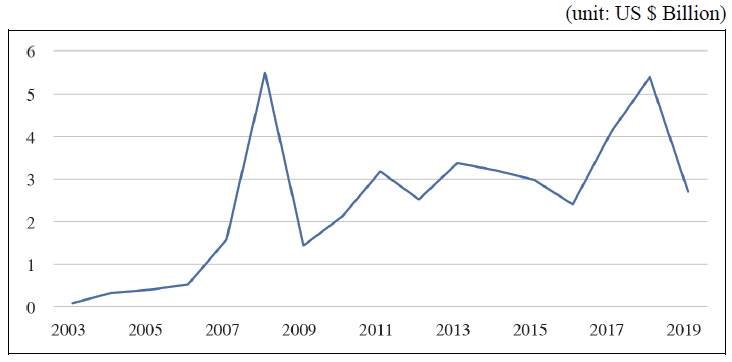

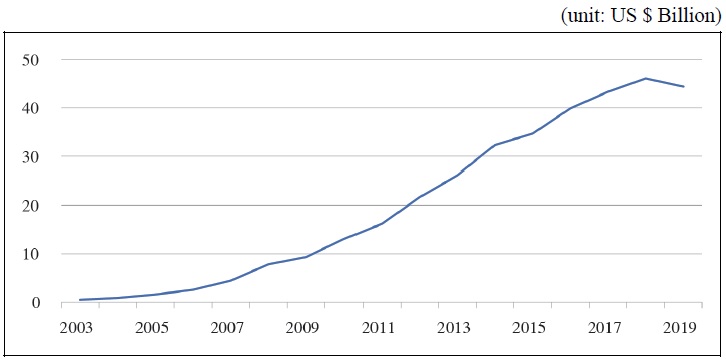

A similar trend is observed in terms of China’s investments flows to Africa. From 2003 to 2019, China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) to Africa grew 100 times (see Figure 5). According to data from China’s statistics bulletin, its stock of FDI in Africa reached $44.4 billion in 2019 (see Figure 6). However, most of China’s direct investments are still localized in Asia, which absorbs close to 70% of its FDI, followed by Europe 12% and Latin America 9%. Africa accounts for only about 3% of the FDIs. There are approximately 10,000 Chinese companies currently operating in Africa (Jayaram et al., 2017), and about 90% of them are private companies, accounting for 70% of China’s FDI to the continent (Yu, 2021). Nonetheless, Chinese state-owned companies are still the largest investors in Africa in monetary terms. In the energy infrastructure alone, Chinese SOEs account for 30% of all energy projects (Darby, 2016). As China continues to implement BRI projects in Africa, Chinese companies are likely to continue to flow to the region because most of the BRI projects are often awarded to Chinese companies.

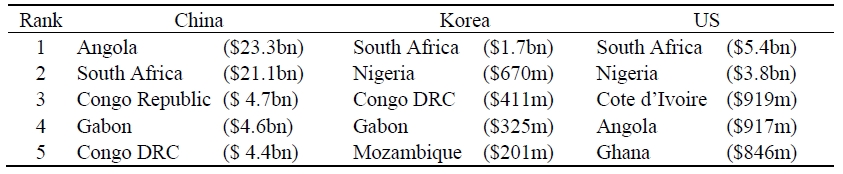

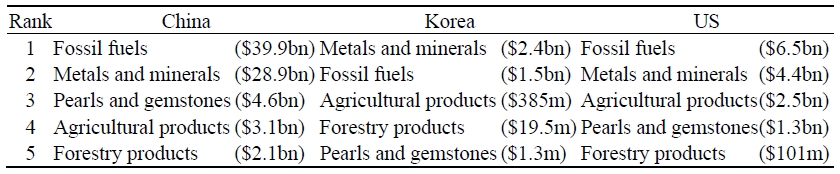

China’s ODA and investment motives in Africa has come under intense scrutiny. Western countries and scholars assert that China’s economic partnership with Africa is exploitative and serves its interests at the expense of Africa. The then US Secretary of state Hillary Clinton stated that China’s development assistance to Africa typifies neocolonialism, undermines good governance and aims at exploiting natural resources. This criticism could be partly because China’s ODA is often mixed with commercial and less concessional financing. Therefore, to examine Chinese motives in Africa, first, it is necessary to look at the sectors to which its ODA is directed. Secondly, it is important to distinguish between China’s investments in Africa into ODA and commercially oriented financing. The OECD classification of sectors is as follows: The social sector includes ODA in education, general and reproductive health, water supply and sanitation, government and civil society and other social infrastructures. The economic sector comprises ODA provided for transport and storage, communications, energy, banking and business. The production sector includes ODA given in support of agriculture, forestry and fishing, industry, mining and construction and trade and tourism. It can be expected that if China’s ODA is driven largely by resource exploitation, it should allocate a significant share of its ODA to production sector under which mining falls. Nonetheless, according to statistics from AidData, a disproportionately large share of Chinese ODA goes to economic sector (54%), followed by social sector (20%) and production sector (9%). On the types of financing, Dreher et al. (2015) disaggregated China’s financial flows to Africa into ODA and commercial financing. Their analysis finds that China’s ODA to Africa is not related with resource extraction but is rather driven primarily by foreign policy. Instead, China’s less concessional forms of official financing are more related with its economic interests in Africa. It can therefore be concluded that China’s strategic cooperation with Africa has mixed objectives. While China’s ODA to Africa is not systematically related with resource richness and resource seeking, a critical examination of trade and investment relations show that China’s eminent trading partners are resource rich countries. In 2019 for instance, oil, metal and mineral producers from sub-Saharan Africa comprised China’s top-5 trading partners. This trend is similar to Korea and US’ top-5 trading partners from Africa (see Table 3). Fossil fuels, metals and minerals comprise the top-2 import items from sub-Saharan Africa to China, Korea and the US. Other main import items from Africa to China, Korea and US are agricultural products, forestry products, pearls and gemstones (see Table 4). This statics implies that China’s top import items from Africa are not different from that of Africa’s other trading partners. This research further argues that African economies are agrarian and resource-based. Therefore, it is reasonable that these are inevitably Africa’s top export items to their trading partners.

It is undeniable that Africa is experiencing rapidly evolving consumption patterns driven by changing demographic trends. Thus, China’s trade and investment relations with Africa is partly motivated by the continent’s growing demand arising from the expanding middle class. Africa’s middle class is 350 million people (Lufumpa et al., 2014) compared to China’s 400 million people. This growing middle class is creating demand for sophisticated industrial goods. African countries are also experiencing a rapid urbanization that is spurring demand for infrastructure development. To meet this demand, African countries collectively need $130-170 billion per year, but has a financing gap of $52–$92 billion (Kouadjo, 2019). Savvy Chinese firms are bridging the gap by investing these areas.

A survey of three African countries in 2019 shows that all the countries’ favorable attitude towards China surpasses their unfavorable opinions: Nigeria 70% favorable, 17% unfavorable; Kenya 58% favorable, 25% unfavorable; South Africa 46% favorable, 35% unfavorable (Silver et al., 2019). Another survey found that US still has more influence than China among leaders in sub-Saharan Africa (Custer, 2018). Nevertheless, US is lagging behind in North Africa and the Middle East. The US has more influence in many policy areas, including governance and social and environmental policies. China on the other hand is quite influential among African leaders involved in economic policy and particularly, it eclipsed the US infrastructure influence in 2017 (Custer, 2018). This implies China’s infrastructure diplomacy is helping it to gain greater leverage in Africa. This is not surprising because many African countries align themselves with China’s economic development model. China’s infrastructure development in Africa is particularly salient in opening up the continent for trade. African economies have stagnated due to barriers to trade and flow of businesses. With the launch of Africa Continent Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), investment in infrastructure is critical to promoting intra-continental trade and spurring Africa’s economic growth. Additionally, China is most influential among leaders from countries that are heavily dependent on Chinese grants and loans (Custer, 2018). China provides an alternative source of financing for African countries with less conditions compared to US and Western countries. This competition between China and traditional donors could help to break the barriers to accessing finance for projects in Africa. From the perspective of developmental impact, China’s investment in the social sectors were found to be more responsive to the needs of Africa (Guillon and Mathonnat, 2020). China’s commercial engagement in Africa has also had positive direct and indirect impact on resource-rich countries in Africa (Drummond and Liu, 2013). According to IMF, Africa’s growth in the past twenty years was mostly due to increase in commodity demand from China (Chen and Nord, 2017). By diversifying its trading partners, Africa reduced volatility of its exports and sustained growth even when advanced countries were in deep economic recession. Doku et al. (2017) finds that China’s FDI have a positive impact on Africa’s economic growth. But other studies found the impact of China’s trade and FDI on Africa is conditional on quality of institutions in Africa (Renard, 2011; Miao et al., 2021).

V. Expanding Korea’s Diplomatic Space in Africa

In the ASEAN, Korea has avoided direct competition with China. Similarly, while implementing its middle power strategies in Africa, Korea does not have the financial resources to compete with China. Therefore, cooperation in areas of mutual interest is the most reasonable way for Korea to achieve its ambitions in Africa alongside the growing Chinese influence. This might well prove a difficult balancing act in which Korea does not want to antagonize the US. Indeed Korean and China’s strategies in Africa are complementary rather than competitive. Cooperation between China and Korea is tenable because China has already signaled willingness to partner with Korea. For instance, China invited Korea to participate in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), one of China’s key diplomacy strategies in Asia. China has also been open to cooperating with other powers on BRI, but they are yet to sign onto the initiative (Chaudhury, 2019). As China’s economic growth is gradually slowing down, it will likely need cooperative partners to implement BRI projects in Africa. Korea has been cooperating with Japan- a country it does not enjoy cordial relations with, to implement development projects in Africa. This is another indication that cooperation with China is a possibility. There are several areas of mutual interest where China and Korea can collaborate in pursuit of their interests in Africa. China emphasizes ‘peaceful rise’ - promoting a peaceful international environment, and Korea is equally pursuing a policy of promoting peace and security in Africa. Engaged in a continent that is torn by conflicts and war, China and Korea can combine their resources to promote peace initiatives in Africa. Political stability of Africa will guarantee its economic growth as well as provide a conducive environment for investment partners like China and Korea. Infrastructure is another potential area of cooperation because both Korea and China achieved rapid economic growth by means of prodigious investment in infrastructure. While China has been willing to cooperate with other powers on BRI projects, they are yet to sign onto the initiative. One reason for this reluctance is that China’s intention is unclear, and BRI is sometimes interpreted as part of its strategy to change the global status quo. Nevertheless, investment in infrastructure in developing regions should be seen as provision of global public goods that promotes common development. Another strategy for Korea is to establish a cooperation mechanism with other middle powers in Africa such as India. The advantage of participating in joint projects with India is that it cannot overshadow Korea’s identity. Moreover, India has had a long history of engagement in Africa that would be vital in promoting their middle power ambitions and interests in Africa.

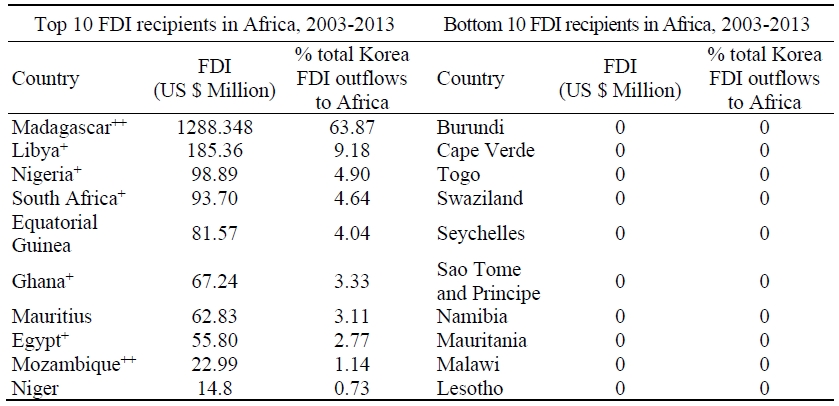

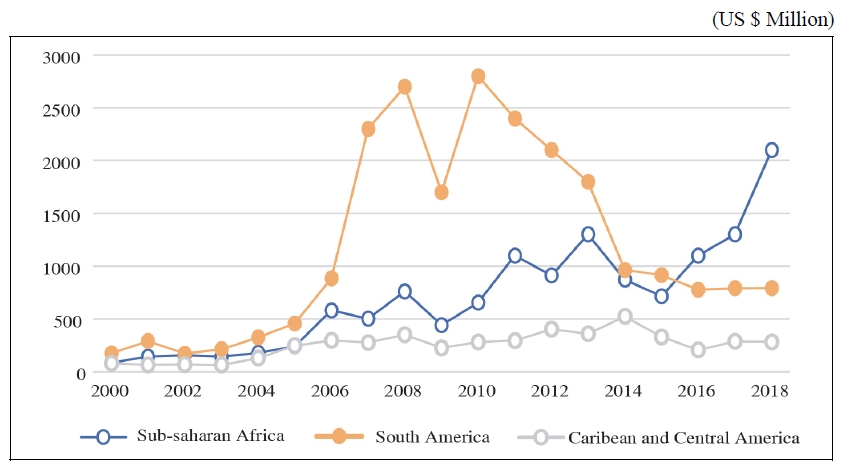

As Korea cooperates with other powers in Africa, it must also pursue independent diplomatic space that will guarantee it visibility, unique identity and recognition. This would require Korea to enlarge its diplomatic space in Africa in niche functional areas and implement them with energy. Development cooperation is one of Korea’s niche functional areas (Botto, 2021). Korea’s development cooperation initiatives have been more vigorously deployed in Asia, even though recently it has increased ODA to Africa, implying it is cognizant of Africa as a key partner. ODA in particular is an important tool because Korea’s ODA projects involves diffusion of its development model. Nonetheless, unlike China that uses two-track diplomacy combining both bilateral and multilateral platforms that have increased China’s influence (China Power Team, 2021), Korea’s diplomacy to Africa has been limited to bilateral platforms. Thus in order to increase its influence in Africa, Korea needs to augment its public diplomacy tools with formal diplomatic exchanges. This includes the establishment of diplomatic missions in more African countries (Monareng, 2016). Evidence demonstrates that investment relations between Korea and Africa are stronger in countries that have either established their diplomatic missions in Korea, or those in which Korea has its diplomatic missions (see Table 5). Among the top-10 recipients of Korea’s FDI, eight are countries that have established their diplomatic missions in Korea or have Korea’s diplomatic missions, except Niger and Mauritius. None of the bottom-10 recipients of Korea’s FDI have their missions in Korea neither do they have Korean missions. This shows that Korea has been successful in establishing stronger economic ties with Africa through official diplomatic channels. Moreover, trade between Korea and Africa surpassed its trade with South America, which was previously Korea’s biggest market in developing regions outside Asia (see Figure A1).

Additionally, Korea is stronger in environmental policy compared to China. In fact, Chinese companies have been accused of neglecting environmental impact in their projects in Africa, sometimes causing serious environmental damage (Mambondiyani, 2019). Climate change agenda has gained traction in Africa as policy makers recognize that it impacts developing economies that rely on rain fed agriculture the most. Yet they have limited capacity to prevent or respond to climate change disasters. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2030, climate change will lead to 250,000 additional deaths from malaria, malnutrition and diarrhea (WHO, 2021). Korea can intensify environmental diplomacy in Africa, and provide technical assistance in environmental policy, invest in climate action and collaborate with Africa to finance clean technology and renewable energy.

Beyond money, other soft power diplomacy instruments can complement development assistance to amplify influence in Africa. Custer (2018) found that China has more influence in countries whose leaders have had greater interaction with Communist Party of China. However, China has less influence in countries that have more leaders who were educated in US and have a higher number of Fulbright scholars. In this context, Korea can intensify soft power diplomacy in core competency areas. For example, both China and Korea have deployed cultural diplomacy towards Africa. However, China’s history of ideological campaigns in the period of Cultural Revolution has created suspicion regarding its intention in spreading its culture. This is reinforced by China’s overbearing state-centric approach to diplomacy. In some countries in Europe and US, CIs have been rejected on grounds that it is China’s tool for propaganda and ideological campaign (Huang, 2020). Korea has no history of attempting cultural or civilizational hegemony, which makes its cultural exchanges more persuasive to cooperative partners. In addition, Korea’s culture contains shareable values and intersecting interest with Africa. African countries view Korea as a case of socio-cultural and socio-economic success to mimic and often compare its socio-cultural and socioeconomic conditions with their own. Its cultural values such as hard work and endurance, resulting in upward mobility are transnational (Singhal and Udornpim, 1997). As such, Korea needs to escalate cultural diplomacy in Africa by increasing investment in cultural programs. Unfortunately, Korea is yet to fully leverage its education exchanges with Africa. This author conducted a pilot interview with students from East and West Africa who studied in Korea to know their views about Korea. Those interviewed had been in Korea for at least 12 months and were randomly sampled based on convenience sampling. All the respondents were graduate school students with 30.8% being female and 69.2% male. 23% were from Kenya, while Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda and Tanzania each had 15.4% of the respondents. The interview revealed that 53.8% have some negative opinions about Korea. When they were asked their perception of China, 61.5% expressed positive opinions. However, they are more confident about Korea’s quality of education 76.9% compared to China 38.5%. The negativity could be due to cultural distance between Korea and Africa. This means there is need for more effort to integrate the students in Korea during their educational sojourn to lower cultural barriers.

VI. Conclusion

China and Africa have had a long history of engagement. This history is characterized by political as well as economic exchanges and China attaches great significance to the accumulation of emotional resources in their relations. This draws from the history solidarity with each other in the face of domestic and global challenges. While China’s diplomacy towards Africa had phases of decline and reengineering, one constant is that it has been continuous and consistent irrespective of the domestic or international environment facing China or Africa. China has invested significant amount of resources in innovating and institutionalizing its diplomacy approach towards Africa. Its diplomacy strategy permeates almost every economic and social stratification in Africa. The cooperation model incorporates diverse actors and runs across various aspects of the governance institutions. With the innovations, China’s has embraced new instruments such as technology, the news media, culture and social economy. Its prioritization of Africa’s industrialization as the basis of cooperation also resonates with African leaders. China’s Investments in social infrastructure are equally increasing in areas such as medical facilities, schools, stadia, modern conference facilities and affordable housing. For instance, China has partnered with Kenya government to build affordable housing units, one of the flagship projects aimed at tackling housing shortage and cost constraints to home ownership in the country. While there is no denying that China’s infrastructure investment in Africa is playing a crucial role in expanding intra-continental trade in the region, African countries are currently heavily indebted to China. This is because its economic assistance involves less concessional terms thus more expensive than Africa’s traditional partners. To reverse this trend, China should increase the proportion of concessional loans to Africa. It should also adopt a blended financing model, combining Chinese financing with Western resources to finance infrastructure projects in Africa. Most of the Chinese ODA comes with a tied element, which requires some of the materials to be imported from China or the implementation of the projects to be carried out by Chinese companies. This increases the cost of the projects due to lack of competitive bidding. Opening the projects to international competitive bidding would therefore bring greater benefits to Africa.

China’s energetic insertion in Africa through its diplomacy activities has profound implications for the continent’s traditional partners as well as countries with middle power ambitions in Africa. For the traditional partners, China’s cooperation with Africa is a challenge to adopt a pragmatic approach towards Africa and shift towards what is perceived as mutual respect and win-win economic partnership. This is because with the increasing competition from China and middle powers like Korea, Africa is no longer at the mercy of its Western allies. Despite China’s growing influence in Africa, Korea can achieve its interest in the region if it focuses its diplomacy resources in areas of its core competencies, such as culture, education and vocational training, environment and development cooperation. Both Korea and China are viewed favorably by African countries as peers and a model due to their miraculous economic transformation. Since they are late developers, their development models provide a suitable template to Africa. Korea’s ambitions are not a serious threat to China’s interests in Africa. Moreover, Korea and China’s approach to Africa are complimentary rather than competitive. This means they could collaborate in implementing projects of mutual interest. As they do so, however, Korea must continue to invest in activities that maintain its unique identity. African countries are adopting the ‘Look East’ policy, which means relations with China and Korea is likely to grow. This will create opportunities to those who understand their culture and business models. This paper therefore argues that China-Africa cooperation will in the long-term benefit both China and Africa. While China mainly imports natural resources from Africa, it is incumbent upon African countries to diversify their product portfolio to benefit from their trade relations. Furthermore, this research has shown that the composition of trade between China and Africa is not varied from Korea and the US.

Tables & Figures

Table 1.

Summary of Evolution of Chinese Public Diplomacy towards Africa

Source: Author based on literature.

Figure 1.

Trends in Chinse Official Development Assistance to Africa

Source: AidData.

Figure 2.

Percent of Chinese Official Development Assistance by Region (2000-2014)

Source: AidData.

Figure 3.

Percent of Chinese Number of Projects by Region (2000-2014)

Source: AidData.

Table 2.

Number and Percent of International Students Studying in China by Continent

Source:

Figure 4.

China Africa Trade

Source: UN Comtrade.

Figure 5.

China’s FDI Flows to Africa

Source: Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward FDI.

Figure 6.

China’s FDI Stock in Africa

Source: Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward FDI.

Table 3.

Top-5 African Exporters to China, Korea and US (2019)

Notes: Oil producers -Angola, Gabon, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire; Metal and mineral producers-South Africa, Congo Republic, Congo DR, Ghana, Mozambique.

Source: Compiled by author from Resource Trade Earth.

Table 4.

Top Import Items for China, Korea and US from Africa (2019)

Source: Compiled by author from Resource Trade Earth

Table 5.

Korea’s Top-10 and Bottom-10 FDI Recipients in Africa

Notes: (+) Countries with established diplomatic mission in Korea; (++) Countries with Korean diplomatic mission.

Source: Compiled by author from OECD statistics.

APPENDIX A.

Appendix Tables & Figures

Figure A1.

Korea’s Exports to sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America

Source: Compiled by author from Resource Trade Earth.

References