- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 19, No. 1, 2015. pp. 99-114.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.JEAI.2015.19.1.292

Number of citation : 0China’s Debt Woes: Not Yet a “Lehman Moment”

|

Shalendra D. Sharma |

University of San Francisco |

|---|

Abstract

What explains the sharp increase in the Chinese economy’s indebtedness, in particular the China’s onshore corporate debt? Has the overall debt burden reached a threshold where it poses a systemic risk, thereby making the economy vulnerable to a “Lehman Moment” - with disorderly unwinding of the private sector and sovereign debt? What are the short and longer term implications of China’s growing debt problems on domestic economic growth and the broader global political economy? What has Beijing done to ameliorate the problem, how effective were its efforts, and what must it do to deal with this problem?

JEL Classification: E5, F6, R5

Keywords

Sovereign Debt, China’s Corporate Debt, Shadow Banking, Subnational Government, Chinese Economy

I. INTRODUCTION

According to a 15 June 2014 report by the rating agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P), China has reached an ominous milestone.1 The country’s $14.2 trillion corporate sector debt (or debt owed by non-financial companies) is the highest in the world, exceeding even the world’s biggest debtor, the United States which has an estimated $13.1 trillion in corporate obligations.2 S&P estimates that if the current pattern holds, China’s debt and refinancing needs will reach $20.4 trillion in 2018 - or one-third of the total worldwide corporate borrowing (Table 1). More troubling, S&P estimates that anywhere between one-quarter to one-third of China’s corporate debt comes from the country’s “shadow banking sector” - a complex and sprawling network of nonbank lenders that serves borrowers who otherwise would have difficulty accessing credit.3 According to S&P estimates, the debt of China’s shadow banking sector is between $4 trillion to $5 trillion. This suggests that roughly 10 percent of global corporate debt is exposed to the risk of a contraction.

However, corporate debt makes up just one component of China’s debt - albeit, it is the largest component. A sovereign’s “total debt” includes government debt, the debt of its financial institutions, non-financial businesses and households. According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), China’s total debt stood at RMB 111.6 trillion (about $18.5 trillion) at the end of 2012 - or 215.7 percent of that year’s GDP. Of this amount, corporate debt totaled 58.76 trillion yuan which equaled 113 percent of the country’s GDP in 2012, government (including local government4) debt totaled 27.7 trillion yuan or 53 percent of GDP, the household sector debt totaled 16.1 trillion yuan and bonds issued by the financial sector totaled 9.13 trillion yuan.5

Yet, these figures are probably on the conservative side because calculations of debt ratios can vary widely depending on types of credit included. And in the case of China, “government debt” does not always include the debt owed by the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the state-owned banks, and the various special purpose asset-management companies, including the “local government financing vehicles” or LGFVs (which are commercial “window” companies set up by local governments to access credit) which hold large volumes of nonperforming loans. Not surprisingly, Standard Chartered estimates that as of March 2014, China’s total debt stood around 142 trillion yuan ($22.7 trillion), or 245 percent of GDP - a sharp increase from about 150 percent in 2008.6 However, according to Standard Chartered, by June 2014, China’s total debt-to-gross domestic product ratio had reached 251 - a sharp increase from 147 percent at the end of 2008.7

1)

2)China’s corporate sector is large and complex and includes the state-owned banks and state-owned enterprises involved in key industries such as oil and gas, coal, steel, construction, machinery and infrastructure.

3)The

4)In China, “local governments” cover a broad range of entities, including the provincial, prefectural, city, county, townships and the village level.

5)“China’s Total Debt at 215 Percent of GDP in 2012: CASS,” December 23, 2013. Caijing <

6)Yangpeng, Z. 2014. “Standard Chartered: Nation’s total debt surges to $22.7 trillion,” China Daily, June 19. <

7)Anderlini, J. 2014. “China debt tops 250% of national income,” Financial Times, July 21. <

II. CHINA’S GROWING DEBT WOES

In order to blunt the adverse impact of the external shock triggered by the global financial crisis of 2008, in particular, the sharp fall in export demand from the advanced economies, Beijing implemented a massive stimulus program ostensibly designed to structurally shift or “rebalance” the Chinese economy from its export-driven growth path to one led by investment spending. Specifically, in early 2008, Beijing put in place a massive RMB 4 trillion (about US$600 billion) stimulus package to boost the nation’s economy. The central government’s total funding was around RMB 1.18 trillion with the rest funded by the local governments via the LGFVs. Monetary policy also played a key role in supporting the stimulus program. To this effect, the country central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut the policy rate four times from 7.5 percent in August 2008 to 5.3 percent in December 2008, and maintained the rate through September 2010. Moreover, the PBoC lowered the required reserve ratio on RMB deposits from 17.5 percent in August 2008 to 13.5 percent in December 2008, including relaxing bank loan quotas and lifting broad money (M2) growth targets till end-2010. Yao notes that broad money (M2) “ballooned to 110.7 trillion yuan (HK$140 trillion) - almost twice the country’s gross domestic product” by end-2013.8

Because the stimulus was mainly a credit (rather than a fiscal) based and financed mainly through new bank lending, stimulus spending drastically increased bank lending - with traditional banks issuing new financial products in order to capitalize on the credit bonanza. Predictably, this only added to the money supply. According to Minxin Pei, between 2009 and June-2012, “Chinese banks have issued roughly 35 trillion yuan ($5.4 trillion) in new loans, equal to 73 percent of China’s GDP in 2011. About two-thirds of these loans were made in 2009 and 2010, as part of Beijing’s stimulus package. Unlike deficit-financed stimulus packages in the West, China’s colossal stimulus package of 2009 was funded mainly by bank credit (at least 60 percent, to be exact), not government borrowing.”9

Although, this large-scale injection of liquidity helped the Chinese economy better withstand the adverse contagion effects stemming from the global financial crisis, such an excessive volume of loose money triggered a veritable spending spree -- fueling a credit and real estate bubble. Much of this problem can be attributed to the peculiarities of China’s central-local relationships - which besides unleashing interjurisdictional competition, also generates perverse incentives (Chen, 2008; Liu et al., 2012). Specifically, despite the fact that local governments are expected to deliver the bulk of the social services, they have limited revenue source as the central government collects (and discretionally distributes) tax revenues.10 In fact, since the introduction of the 1994 Budget Law, “the central government has effectively centralized the most lucrative sources of revenue, including value-added tax (VAT), resource tax, and personal and enterprise income tax. In 2002, the central government further ordered local governments to channel 50 percent of personal and enterprise income tax to the central government” (Lu and Sun, 2013). On the other hand, despite the fact that the local governments spending burdens have increased, they (local governments) are statutorily prohibited from borrowing from the formal banking system, and till recently, not even allowed to issue municipal bonds.11

To subnational and local governments suffering from serious fiscal imbalances, squaring the mismatch between their revenues and expenditures has meant getting around prohibitions on borrowing (Zhan, 2013). Indeed, with Beijing’s tacit support, local governments ordered the state-dominated banks to increase lending to projects and businesses that could quickly generate employment. More often than not, this meant more investments in large scale (and costly) infrastructure and construction projects, including the “pet projects” of influential and vested political and economic interests. Because local governments are responsible for implementing the infrastructure investments funded with the stimulus they literally enjoyed a free rein when it came to borrowing - and they borrowed freely and often. Furthermore, since local governments have limited sources from which to generate revenue, they creatively used their off-balance sheet financing such as the LGFVs to borrow generously to finance their capital expenditures.12 Again with the tacit approval of central authorities, local governments used a plethora of LGFVs (as well as UDICs or “urban development and investment companies”) to serve as their principal financing agents to facilitate borrowing as well as tap the stimulus largesse by issuing bonds.13 By end-2010, over 6,500 LGFV’s had been set up (IMF, 2013).

This uncontrolled borrowing binge - often as large as the outsized ambitions of local authorities - soon outstripped the revenues of local governments, and in the process, further multiplying the accumulated debt. At the heart of the problem is that even as the LGFVs rapidly build-up huge mismatches between their short-term borrowing and the long-term investments they have (and are) financing, the local governments lack the sufficient cash flow to service their debt and related obligations. This is not only because investments in infrastructure and real-estate are notorious for not generating sufficient cash flow to service debts, the majority of the LGFVs are depended on land sales and high property prices to meet their obligations.

Indeed, local government borrowings have been increasingly speculative as many have pledged “anticipated” revenue from future land development and real estate sales as collateral. Compounding this, the widespread misallocation of resources at the local level due to politically-motivated lending in wasteful “white-elephant” ventures, including “missing” funds” through outright theft and pervasive corruption, further exacerbated the debt problem. As Lu and Sun (2013) presciently note: “since the receipts from the sale of land lease rights are the main sources for debt repayment, a correction in real estate prices could hurt the debt servicing ability of local governments and LGFPs, and impair banks’ asset quality. In the worst case scenario, it may trigger contagion between the financial sector and the sovereign.” With the demand for credit soon outstripping supply, and the numerous “vanity” projects, including the quick get-rich schemes that had propped-up had difficulty securing formal bank loans, local governments, including private borrowers turned to the shadow banks for credit. For their part, the shadow banks obliged not only because they were able to circumvent government loan quotas, but also because of their close links with the formal banking system and powerful vested interests made such transactions both easy and lucrative. In short order, the uncontrolled credit binge, compounded by declining corporate profitability (despite the high levels of investment), and growing overcapacity exacerbated the corporates and local governments debt problems leaving many highly leveraged and with a debt hangover. The corporate sector’s was particularly hard hit (compared to government and household debt), because declining profitability and overcapacity even reduced viable companies’ capacity to service their loans and interest payments.

8)Yang, Y. 2014. “Shadow banking the biggest threat to China’s economy,” South China Morning Post, March 10. <

9)

10)According to

11)However, a pilot project in 2011 approved by Beijing now allows Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangdong and Zhejiang to issue bonds.

12)Indeed,

13)According to a recent report, “Regional governments set up more than 10,000 local financing units to fund construction projects after they were barred from directly issuing bonds under a 1994 budget law. Local-government debt swelled to 17.9 trillion yuan ($2.96 trillion) as of June, compared with 10.7 trillion yuan at the end of 2010, according to data compiled by the National Audit Office.” “China LGFV Sells First Dollar Bond as Yuan Borrowing Costs Rise,” 2014,

III. BEIJING’S BELATED RESPONSE

Seemingly alarmed by the rapid and uncontrolled growth of credit and worsening credit quality, the PBoC along with China’s key regulatory agency, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC), beginning in August 2010, jumped into action by putting in place a series of measures (indeed sanctions), to both rein-in and restrict credit growth.14 Most notably, the PBoC raised the bank reserve requirement ratios to an unprecedented 21.5 percent for large institutions in June 2011; imposed deposit reserve requirements to collateral deposits; made it mandatory for banks to bring their high-risk off-balance-sheet activities back onto their books; and put in place new capital requirements on trust companies. Yet, these measures proved too little and too late because Beijing did not want to tighten too much because of concerns about triggering a “hard landing,” and concerns that the large debt build-up and the overall poor credit quality of much of the new loans already posed a huge problem. As a result, the half-hearted attempts to cool the economy by limiting the money supply and tightening the regulation and supervision of commercial and shadow banks backfired. Instead of having the effect policy-makers desired, monetary policy tightening had a perverse effect in creating a huge demand for credit outside the formal banking system. As credit dried up, individual investors, real-estate developers, private and state-owned enterprises, and local governments need for financing grew even more desperate. In their search for badly-needed cash infusions they turned to the shadow banks. Again, the shadow banks were only too happy to oblige, raising cash by floating all manner of products - with the “wealth management products” (WMPs) being the most ubiquitous. Not surprisingly, the 2013 nation-wide audit conducted by the Xi Jinping administration confirmed that the level of central and local government debt had expanded as a percentage of GDP.

Evidently, in a short period of time shadow banks fueled an alarming build-up in the debt owed by private businesses, property developers, state-owned and private enterprises and local governments, while at the same time carrying liabilities they cannot possibly honor. For example, local governments have invested massively in infrastructural projects, and in collusion with property developers, in real estate projects. Yet, there are already growing numbers of “ghost cities” or blocks of empty units which serve as a costly testament of excessive construction - albeit, there is an undersupply of affordable housing in China.15 Similarly, the investments in infrastructure have not been commensurate with either need or budgetary wherewithal. Arguably, as China’s growth slows down, the returns will decline even further, but debt burdens will continue to grow with potentially serious ramifications on the already weak local government fiscal base. As Rabinovitch notes, “in all, there are about $660 billion of trust products up for repayment or refinancing this year. Chinese shadow banks, by definition, have been focused on customers - miners, property developers and local governments - that regulators have deemed too risky for banks, so more problem loans are a certainty.”16 In fact, if China’s real-estate bubble bursts and the local governments begin defaulting on their debts, the balance sheets of Chinese banks will rapidly deteriorate with the non-performing loans exploding to unimaginable levels. Suffice it to note that if such a scenario were come to pass Beijing and the global economy could potentially have an unprecedented crisis on their hands.

14)The CBRC was established in 2003 and is responsible for regulation and supervision of the banking sector. Its functions are separate from the PBoC which is responsible for monetary policy and financial system stability. To its credit, the CBRC has helped to strengthen prudential standards and overall improvements in bank governance. The five large state-controlled banks include the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC); China Construction Bank (CCB); Bank of China (BOC); Agricultural Bank of China (ABC or AgBank); and the Bank of Communications (BoCom). China also has three state-controlled “Policy Banks”: the Agricultural Development Bank of China (ADBC); China Development Bank (CDB); and the Export-Import Bank of China. Altogether, the five state-controlled banks account for about 50 percent of Chinese banking assets and deposits and are majority-owned by the Chinese state - albeit, they do have private shareholders.

15)According to a recent IMF study, “The real estate market… together with construction… directly accounted for 15 percent of 2012 GDP, a quarter of fixed-asset investment, 14 percent of total urban employment, and round 20 percent of bank loans….Recent data suggest that several regions are in oversupply. Residential real estate inventories have increased sharply in Tier III and IV cities, as well as in the industrial Northeast (including Shenyang and Changchun) and parts of the Coast (including Hangzhou, Dalian, Fuzhou and Wenzhou). Commercial real estate, meanwhile, appears to be in oversupply across most regions.” International Monetary Fund, 2014. “People’s Republic of China: 2014 Article IV Consultation,” IMF Country Report No. 14/235. <

16)Rabinovitch, S. 2014. “Economic danger lurks in Chinas shadow banks,”

IV. THE WARNING AND BEIJING’S STRENGTHS

To the markets, the sharp increase in credit expansion in China, in particular, the unprecedented increase in the levels of private domestic credit coupled with the banking sector’s high exposure to struggling businesses heightens the risk of a potentially destructive banking crisis. Similarly, the corporate debt situation is deemed to get even worse - at least in the near term - as economic growth slows down, corporate profits decline (in some cases sharply), and corporate defaults become more common. Not surprisingly, the onshore corporate default by a Chinese company (Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy Science & Technology Company), in early March 2014 when it failed to make a 90 million yuan ($14.46 million) interest payment made news as it was the first default of a domestic corporate bond since China established a bond market in 1992. This default was soon followed with more bad news with the Shanxi Haixin Iron and the Steel Group Company Limited defaulting on their bank loans. The defaults vividly highlighted the risks associated with high leverage and debt. Yet, the defaults were unprecedented not because companies with very modest debts were allowed to fail, but more importantly, because Beijing allowed them to fail. Not only, the underwriter of Chaori’s bond is China Securities (which is fully owned by the central government), Premier Li Keqiang candidly noted that any future defaults on bonds and other financial products may be “unavoidable” because the government is determined to allow market forces to play a greater role in the economy. To the markets, such blunt remark and action underscore that Beijing may no longer “implicitly guarantee” loans raised fears about the overall credit quality of Chinese corporates and whether the economy was on the brink of a systemic crisis. Indeed, to some, the defaults signaled the start of the unraveling of China’s financial system under the weight of its own version of a “Lehman Moment” - with a disorderly unwinding of private sector and local government debt.17

Nevertheless, despite China’s worsening debt problems, such conclusions are unduly pessimistic. There are several reasons for reaching such a conclusion. First, when compared with many advanced and emerging market economies, China’s total debt to GDP is relatively modest, and the bulk of government debt is denominated in RMB and held domestically. Second, despite the large size of corporate debt, the primary issuers of corporate debt are domestic as foreign investors are limited to “Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors.” In other words, the bulk of China’s debt is not only held domestically, China’s corporate sector debt is concentrated in a handful of sectors, namely mining, coal, steel and transportation. In fact, Huang notes that China “doesn’t fit the stereotype of a nation which is set to undergo a debt crisis. China actually faces a problem in the area of corporate debt, which as a share of the nation’s GDP is one of the highest in the world. But it doesn’t have any problems in terms of government or household debt. Even in the corporate sector, most firms in China don’t have any issues. The vulnerabilities lie mainly within a small group of large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) which has over-extended and accumulated large debts. However, these debt problems aren’t the same as in the West as these companies are all not only owned, but also backed by either local governments or the national government, meaning that the state is ultimately responsible for the debt. This is why it is unlikely for these SOE’s to trigger a cascading debt problem similar to that in Western economies where private companies have a debt servicing problem.”18

Third, China’s very high national savings rate (totaling about half of GDP) more or less guarantees that the banking sector’s deposit base will remain healthy, besides allowing the authorities to service the debts without much difficulty. Fourth, China’s $3.8 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves and the banking sector whose overall health remains robust (the average capital adequacy ratio for China’s 17 major banks is around 13 percent), the Chinese economy can certainly absorb a significant volume of bad debt without serious repercussion.19 That is, at worst, defaults will only erode the quality of the official banking sector’s loan portfolios.20 Fifth, China does not suffer from the vulnerabilities that have been responsible for triggering financial crises: a sudden large-scale outflow of foreign capital and exit from the local currency by local depositors and domestic and external investors. Rather, Beijing by keeping the capital account largely closed not only keeps domestic savings at home, it also limits capital outflows. Moreover, because Chinese banks including the domestic equity and bond markets have limited foreign exposure, it makes the economy immune to sudden and massive foreign capital outflows. Sixth, China’s bank-dominated financial system is far more stable and less exposed to volatility typical of systems that are heavily depended on equity financing. Not surprisingly, the banking sector has continued to post income growth - albeit, the banks’ asset quality remains a problem. Seventh, the risk of contagion is small as shadow banks only offer relatively simple financial products consisting mostly of direct credit and not complex securitized products. Finally, as long as China continues to experience robust economic growth, its national debt will remain manageable. Given these, the recent defaults should not be viewed as the government’s inability to absorb fiscal losses, but as a warning to investors that they should not view Beijing as a protective “cash cow” providing explicit guarantees to their imprudent, if not, reckless, investments.

17)Cassidy, J. 2014. “Is China the Next Lehman Brothers?”

18)Cited in “China’s debt problems ‘aren’t the same as in the West,” 26 September, 2014. <

19)Boone and Johnson note that “China luckily has substantial scope for absorbing losses. For example, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, one of China’s largest banks, reported $59 billion of operating profit (before loan loss provisions) over the last 12 reporting months… It can use that profit to offset losses on its $1.5 trillion loan book (over and above the $38 billion that it has already provisioned). Even if 10 percent of loans were to eventually default, with 50 percent recovery on those loans, the losses to equity capital could be offset with just two years of profits. Share issuance (already priced into equity markets) could raise further capital if needed. This high profitability of Chinese banks makes them far more resilient than American and European banks. For example, Washington Mutual, which eventually was taken over by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, reported roughly half the profitability of the Chinese banks in the boom years before it collapsed.” Boone, P. and S. Johnson. 2014. “China’s Shadow Banking Malaise,” March 27. <

20)Yu, Y. notes that “the most immediate threat to China’s economic and financial stability is the combination of high borrowing costs, low profitability for nonfinancial corporations and very high corporate leverage ratios....There is no indication that the ratio will decline anytime soon, which is particularly worrisome, given the low profitability and high borrowing costs that China’s industrial enterprises face...With insufficient profits to use for investment, nonfinancial corporations will become increasingly dependent on external finance. As their leverage ratios increase, so will their risk premiums, causing their borrowing costs to rise and undermining their profitability further. This destructive cycle will be difficult to break….Despite these risks, it is too early to bet on a corporate debt crisis in China. For starters, no one knows at what corporate leverage ratio a crisis will be triggered. In 1996, when Japan’s public debt/GDP ratio reached 80%, many Japanese economists and officials worried about a looming crisis. Almost two decades later, the ratio has surpassed 200% - and still no crisis has erupted. Furthermore, China has not yet completed its market-orientated reforms, which could unleash major growth potential in many areas. Given the role that institutional factors play in China’s corporate-debt problem, such reforms could go a long way toward resolving it.” Yu, Y. 2014. “China has breathing space for financial reform,” August 25. <

V. WHAT BEIJING MUST DO

Although, a Lehman moment is not in the cards for China (at least not currently), it does not mean that the economy can prod along or that the much needed economic and financial sector reforms can wait. To the contrary, if credit growth continues unabated and outpace economic growth, the country’s financial system will come under more intense stress. Put bluntly, investments that do not result in growth is simply not sustainable - not to mention that a large proportion of these investments (which are borrowed money), will not get repaid. Indeed, the default of Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy Science and Technology Company underscores the potential risks associated with high levels of leverage. Put more bluntly, the reality is that China already has a debt problem, and high and growing debt burdens invariably results in slower growth, if not stagnation. In fact, China’s neighbor, Japan serves as a cautionary example of a country which failed to rein-in its debt problems with adverse consequences. Although Japan with its unprecedented debt load has managed to avoid a catastrophic economic meltdown, it has not been able to escape the economic stagnation of the “lost decade,” if not “decades.” To mitigate such risks Beijing must address core problems facing the Chinese economy. Namely, in order to rein-in credit growth, Beijing must rebalance the Chinese economy away from its current investment-led growth model to one based more on domestic demand and services. Second, it must reduce the problems associated with moral hazard. Specifically, as long as individuals and businesses believe - even implicitly - that their investments are guaranteed by the government and the formal banking system, funds will continue to flow into risky sectors and products because investors will continue to snap-up products promising lucrative returns. After all, it was the perceived absence of risk (which made credit unusually cheap) that triggered the massive surge in corporate debt issuance in the first place. By sending a clear message that the government will no longer provide future bailouts for unregulated and insured investments, and investors will have to get a “haircut” for their poor and irresponsible decisions will go a long way in curbing speculative and risky activities by forcing both the official and shadow banking sectors to price risk more realistically. And third, Beijing should impose meaningful hard budget constraints on local governments to rein-in uncontrolled spending and limit the current crowding out of credit to speculative and borrowers. Put differently, meaningful crackdown on corruption coupled with the imposition of tough financial discipline on local governments is an urgent task. Finally, the irony is that China is now an outlier - an emerging market economy with very high debt ratio that is more typical of the advanced high-income countries. But, unlike the advanced economies, China has become heavily indebted before it has become rich.

VI. CONCLUSION

In early November, Standard & Poor’s released its much anticipated survey called “Credit China Spotlight” (2014). The report conducted an in-depth survey of 200 of China’s largest corporates as measured by revenue and bond issuance across 18 industries. The study found that weak revenue growth and eroding profit margins have negatively impacted (in some cases rather severely) on earnings –so much so that they have offset the lower capital expenditure. Moreover, many large Chinese corporations suffer from chronic overcapacity, low profitability and rising debt, with the “asset-heavy and capital-intensive sectors are the most vulnerable.” Arguably, the seriousness of the problem has reached the ears of the senior authorities. At the third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in November 2013, an ambitious reform agenda for the years through 2020 covering 16 areas and 60 individual items was announced. Specifically, to address the problem of rising government debt, several measures were announced. These include, (a) the central government increasing transfers to local governments that are in line with fiscal expenditure assignments, (b) local governments will be allowed to issue bonds to finance infrastructure projects, (c) reforms the tax system to simplify and broaden the tax base for local governments, and (d) opening-up the financial sector to more competition from both domestic and foreign private businesses by allowing the private sector to establish small and medium-size financial institutions. No doubt, these are important steps that need to be complemented with deeper reforms. What is certain is that without meaningful reforms, China will not be able to effectively contain debt growth. It remains to be seen if the administration of President Xi Jinping is up to effectively dealing with this critical challenge.

Tables & Figures

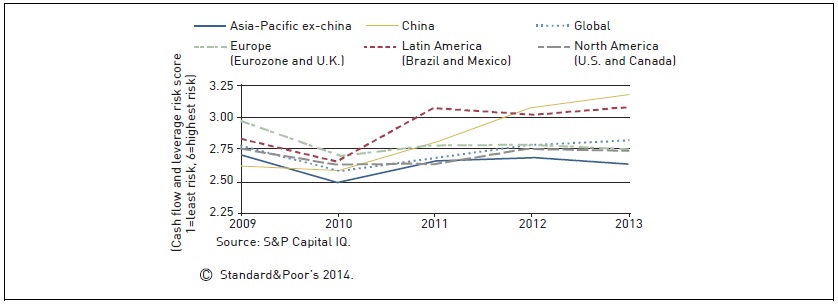

Table 1.

Corporate Financial Risk Trend By Region - 2009 to 2013

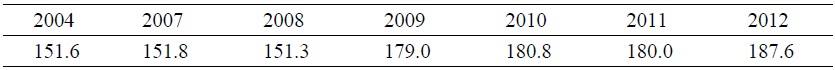

Table 2

Broad Money Growth in China (% of GDP)

Source: World Bank. 2014. World Development Indicators. <

References

-

Chen, A. 2008. “The 1994 Tax Reform and Its Impact on China’s Rural Fiscal Structure,”

Modern China , vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 303-343.

-

FSB (Financial Stability Board). 2013. “Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2013.” November 14. <

https://www.financialstabilityboard.org /publications/r_131114.pdf > (accessed January 15, 2014) -

Ghosh, S., Mazo, I. and I. Otker-Robe. 2012. “Chasing the Shadows: How Significant is Shadow Banking in Emerging Markets?,”

Economic Premise , No. 88. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. -

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2013. “People’s Republic of China: Staff Report for the 2013 Article IV Consultation,” Country Report No. 13/211. <

http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2013/pdf/pr13192an.pdf > (accessed April 10, 2014) - IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2011. People’s Republic of China: Financial System Stability Assessment, IMF Country Report. No. 11/321.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2010. People’s Republic of China: 2010 Article IV Consultation, Staff Report; Staff Statement; Public Information Notice on the Executive Board Discussion, IMF Country Report No.10/238.

-

Landry, P. 2008.

Decentralized Authoritarianism in China: The Communist Party’s Control of Local Elites in the Post-Mao Era . New York: Cambridge University Press. -

Liu, M., Xu, Z., Su, F. and R. Tao. 2012. “Rural Tax Reform and the Extractive Capacity of Local State in China,”

China Economic Review , vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 190-203.

- Lu, Y. and T. Sun. 2013. “Local Government Financing Platforms in China: A Fortune or Misfortune?” IMF Working Paper, WP/13/243.

-

National Audit Office of the People’s Republic of China. 2011. “Report on the Local Government Debt Audit Work,” No. 35. <

http://www.audit.gov.cn/n1992130/n1992150/n1992500/2752208.html > (accessed April 10, 2014) -

PBoC (People’s Bank of China). 2013. “China Financial Stability Report 2013,” Beijing. <

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/publish/english/959/2013/20130813151434349656712/20130813151434349656712_.html > (accessed April 10, 2014) -

Pei, M. 2012. “Are Chinese Banks Hiding “The Mother of All Debt Bombs”?,” The Diplomat, September 10. <

http://thediplomat.com/2012/09/are-chinese-banks-hidingthe-mother-of-all-debt-bombs/?allpages=yes > (accessed April 30, 2014) -

Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services. 2014.

Credit Shift: As Global Corporate Borrowers Seek $60 Trillion, Asia Pacific Debt Will Overtake U.S and Europe Combined. McGraw Hill Financial: Standard & Poor Ratings Services . -

Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services. 2014.

China Credit Spotlight: The Outlook For State-Owned Enterprises. December, McGraw Hill Financial: Standard & Poor Ratings Services . -

World Bank. 2014. World Development Indicators. <

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FM.LBL.BMNY.GD.ZS > (accessed April 30, 2014) -

World Bank. 2013. “China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative Society,” Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. <

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/03/17494829/china-2030-buildingmodern-harmonious-creative-society > (accessed April 29, 2014) -

Zhan, J. V. 2013. “Strategy for Fiscal Survival? Analysis of Local Extra- budgetary Finance in China,”

Journal of Contemporary China , vol. 22, no. 80, pp. 185-203.

- Zhang, Y. S. and S. Barnett. 2014. “Fiscal Vulnerabilities and Risks from Local Government Finance in China,” IMF Working paper, WP/14/4.

-

Zhou, X. 2010. “The Institutional Logic of Collusion among Local Governments in China,”

Modern China , vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 47-78.