- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | Can agricultural export trade openness improve residents' health in China / 2024 / Economic Analysis and Policy / vol.84, pp.1608 / |

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 24, No. 3, 2020. pp. 207-235.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2020.24.3.377

Number of citation : 1An Adverse Social Welfare Effect of Quadruply Gainful Trade

|

University of Bonn, Germany; University of Warsaw, Poland |

|

|

Cracow University of Economics, Poland |

Abstract

Acknowledging that individuals dislike having low relative income renders trade less attractive when seen as a technology that integrates two economies by merging separate social spheres into one. We define a “trembling trade” as a situation in which gains from trade are less than losses in relative income, with the result that global social welfare is reduced. We show that a “trembling trade” can arise even when trade is more gainful in four ways: through trade the absolute income of everyone increases, the income gap in both economies is reduced, as is the income gap between the trading economies. However, trade brings populations, economies, or markets that were not previously connected closer together in social space. As a consequence, separate social spheres merge, and people’s social space and their comparators are altered. Assuming that people like high (absolute) income and dislike low relative income, the aggregate increase in unhappiness caused by the trade-induced escalation in relative deprivation can result in a negative overall impact of trade on (utilitarian-measured) social welfare, if the

JEL Classification: D31, D63, F10, F15, R12

Keywords

Gains from trade, Increase of incomes, Decrease of income gaps, Integration, Change of social space, Low relative income, Quadruply gainful trade, “Trembling trade, ” Social welfare

1. INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION

At least since Stolper and Samuelson demonstrated in 1941 in a formal general equilibrium model that when an economy leaves a state of autarky to engage in trade with other economies, not everyone’s real income rises, a view has been held that if as a result of trade everyone’s income is made to rise (redistributive policies can see to that), one of two potential unwarranted consequences of free trade (that the incomes of some people fall) need not be worrisome. A second concern regarding the repercussions of free trade has been a possible rise in the income gap between the trading economies: even when trade between, say, a relatively rich economy P2 and a relatively poor economy P1 confers gains so that everyone’s income increases, trade can be viewed with some trepidation if the income gap between P2 and P1 widens. However, when everyone’s income increases

A theoretical foundation of the gains from trade can be traced back to Ricardo’s (1817) law of comparative advantage. Rising productivity and increasing national income brought about by international trade, as predicted by Ricardo, are repercussions that were confirmed empirically, for example by MacDougall (1951, 1952), Golub and Hsieh (2000), Melitz (2003), Bernhofen and Brown (2005), Irwin (2005), Amiti and Konings (2007), Goldberg et al. (2010), and Etkes and Zimring (2015). However, since Ricardo’s “Principles,” economists have also been aware that the distributional consequences of trade are distinct from the rising incomes consequences of trade. Anything that exacerbates inequality has for long been considered problematic, trade included. A concern has been expressed that even when the incomes of all involved increase and the income gap between P2 and P1 narrows, trade can still fail to increase global social welfare when, as a result of engagement in trade, the following happens: the income distribution within P2 or the income distribution within P1 or the income distributions within both widen (the incomes of the richer members of P2 increase by more than the incomes of the poorer members of P2 and / or the incomes of the richer members of P1 increase by more than the incomes of the poorer members of P1). This concern is usually based on the trade models of Ohlin (1933) and Stolper and Samuelson (1941). For example, Berman et al. (1998) view trade as a cause of a simultaneous rise in wage inequality in developed and developing economies. Barro (2000) finds that trade openness increased inequality in developing countries. Lundberg and Squire (2003) identify a positive correlation between trade liberalization and higher within-country income inequality. Goldberg and Pavcnik (2007) observe that across a number of developing countries, significant increases in inequality were a typical consequence of trade liberalization after the 1970s. Feenstra and Hanson (1997), Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg (2008), Burstein and Vogel (2011), and Sampson (2014) list a variety of reasons why greater economic integration between countries may cause wage inequality to rise within countries. Antràs et al. (2017), who measure the gains from trade by adding to the classical real income gain a term that measures the inequality cost, conclude that trade-induced increases in inequality “eat up” about 20% of the US gain from trade. Studying European Union integration, Beckfield (2009) observes both a decrease in inequality between countries, and an increase in inequality within countries. On the other hand, Calderón and Chong (2001) find that, at least in developed countries, an increase in the volume of trade is positively correlated with a long-run decline in the in-country income inequality. What the current paper seeks to establish is that even when on all four counts trade is beneficial (namely when it increases the income of every individual in P1 and in P2, narrows the income gap between P2 and P1, narrows the income gap within P1, and narrows the income gap within P2), trade can still fail to raise global social welfare.

In a recent paper, Stark et al. (2018) present a constructive example why trade that increases the absolute income of every member of the trading economies and narrows the income gap between the economies can at the same time lower global social welfare. The core idea of the paper by Stark et al. is that trade affects social relations which, in turn, are likely to bring about changes in social welfare. Trade may modify social relations in a variety of ways, which include revising social ties, broadening social horizons, and forging new social interactions: trade does not occur only in geographical space; it leaves footprints in the social sphere. The participation of economies in trade can enlarge the social space of the members of the economies. This expansion impacts on how these members value and assess the benefits that trade confers. Stark et al. build on the notion that individuals’ preferences are social in nature. This perspective incorporates the concepts of social space, relative income, and relative income deprivation (defined in Section 2 below). Stark et al. use the term “trembling trade” to describe a situation in which the negative effect on the welfare of the trading economies that arises from the trade-induced shake-up of their social spheres is greater than the gains brought about by trade in the form of income increases and reduced income gap between the trading economies.

In this paper we present a general theory of a “trembling trade” - a situation in which gains from trade are less than losses in relative income - and we use the theory to show that even a quadruply gainful trade, meaning trade that increases the absolute income of everyone, reduces the income gap in both of the two trading economies, and narrows the income gap between the trading economies, can lower global social welfare.

Although it is not typical for trade to be quadruply gainful, our strategy is to show that

We view trade as a process which, as a result of market transactions involving an exchange of goods or services, brings populations, economies, or markets that previously were not connected closer together in social space. As a consequence of this integration, separate social spheres merge, and people’s social space and their comparators are altered. Then, the perceived relative incomes of some individuals, calculated in the context of the broader social space, may decrease even if through trade the absolute income of everyone increases, the income gap within each economy is reduced, as is the income gap between the trading economies. Consequently, in and by itself, the integration of social spaces may exacerbate the discontent that some individuals experience from having low relative income. We represent people’s concern about low relative income by means of a measure of relative income deprivation: we say that an individual experiences relative deprivation when his income falls behind the incomes of other individuals who constitute his comparison group. Assuming that people like high (absolute) income and dislike low relative income, we show that the aggregate increase in dismay caused by the trade-induced escalation in relative deprivation can result in a negative overall impact of trade on (utilitarian-measured) social welfare, if the

The trade-generated expansion of a social space can arise via several channels. First, purchased goods convey information about trading partners, in particular about the productivity of labor and about incomes in the partner economy. This channel operates even in the sterile world of perfect Walrasian markets. A second channel results from the interactions of people in non-Walrasian environments where trade requires social interactions aimed at matching trading partners and at mediation which, to different extents, removes the information gap between the trading economies. Third, in order to facilitate and intensify trade, trading partners introduce mechanisms and procedures that also reduce the social divide between them. In the context of international trade, monetary unification (an event that has occurred in Europe seven times since 1999) is one such example.1 Fourth, trade invites, and is often based on, exchanges of traders, trade representatives, trade delegations, and experts of various types. Presence and exposure foster comparisons. Fifth, trade is built on a study of the needs, preferences, consumption habits, and demands of the partners in trade; the expansion of commercial space brings in its wake an expansion of social space. Sixth, trade is often the precursor of migration, and migrants facilitate and intensify cross-cultural awareness and inter-economy social ties.

The remainder of this paper is divided into three main sections. In Section 2 we present an example. In Section 3 we develop a general framework that in subsequent Section 4 enables us to state and prove our main proposition and corollaries, the essence of which are conditions under which, in spite of being quadruply gainful, trade can lower global social welfare. A brief Section 5 concludes.

1)

II. AN EXAMPLE

A numerical illustration helps to demonstrate that a “trembling trade” can arise even when trade between two populations, P1 and P2, is quadruply gainful in the sense that:

1. it increases the income of

2. it narrows the income gap

3. it narrows the income gap

4. it narrows the income gap

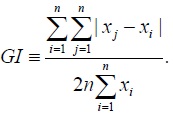

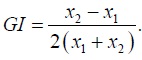

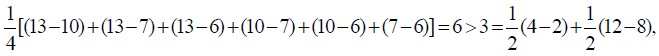

Let populations P1 and P2 consist, each, of two individuals. We let the initial incomes of the individuals in population P1 be 2 and 4, so the average initial income in P1 is 3. When trade occurs between P1 and P2, incomes 2 and 4 rise to 6 and 7 respectively. Consequently, the average post-trade income in P1 is 6.5, and 6.5 > 3. When trade occurs, the income gap within P1, when measured as the difference between the incomes of the individuals in P1, narrows from 2 to 1. The decreased inequality within population P1 is also indicated by a lower Gini index, GI. For a population of

For

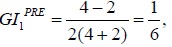

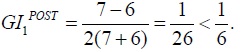

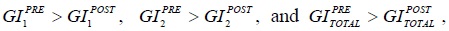

Thus, the pre-trade GI of population P1 is  and the post-trade GI of population P1 is

and the post-trade GI of population P1 is

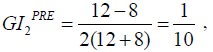

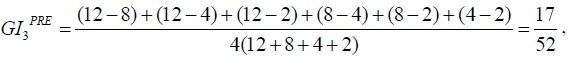

We let the initial incomes of the individuals in population P2 be 8 and 12, so the average initial income in P2 is 10. When trade occurs with P1, incomes 8 and 12 rise to 10 and 13 respectively. The average post-trade income in P2 is, then, 11.5, and 11.5 > 10. When trade occurs, the income gap within P2 narrows from 4 to 3. The GI of population P2 is lowered: the pre-trade GI of population P2 is  and the post-trade GI of population P2 is

and the post-trade GI of population P2 is

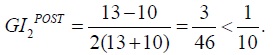

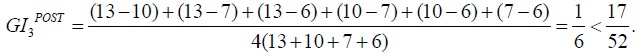

The initial gap between the average incomes of P2 and P1 is 10 - 3 = 7. The post-trade gap between the two populations, when measured as the difference between the average incomes of P2 and P1, is 11.5 - 6.5 = 5, and 5 < 7. The corresponding GI shrinks: the  whereas the

whereas the

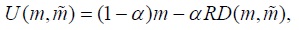

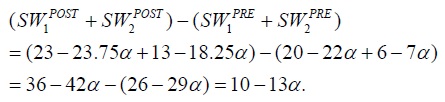

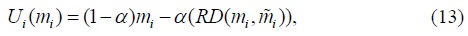

We assume that the individuals derive utility from (absolute) income, and disutility from low relative income, and that they assign the weight

where  is the income vector of the individual’s comparison group including the individual (prior to trade, this group is population P1 or population P2, whereas post trade this group is population

is the income vector of the individual’s comparison group including the individual (prior to trade, this group is population P1 or population P2, whereas post trade this group is population

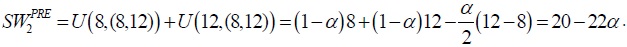

where  denotes the size of the vector

denotes the size of the vector

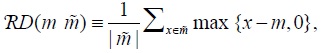

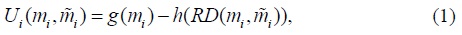

Given this utility characterization, we obtain the following results regarding the changes in a utilitarian measure of social welfare brought about when trade occurs between the two populations. When, for example, we write next  The level of social welfare of the pre-trade, autarkic P1 is

The level of social welfare of the pre-trade, autarkic P1 is

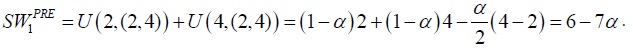

The level of social welfare of the pre-trade, autarkic P2 is

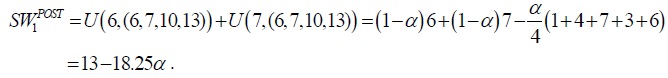

The level of social welfare of post-trade P1 when the P1 individuals are in the comparison group with income vector (6,7,10,13), namely of P1 as part of an integrated

The level of social welfare of post-trade P2 when the P2 individuals are in the comparison group with income vector (6,7,10,13), namely of P2 as part of an integrated

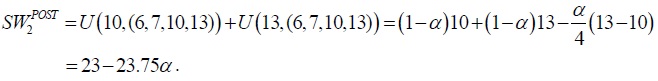

The change of global social welfare brought about by trade is

It follows, then, that global social welfare declines if 10 - 13

The preceding calculations illustrate a possible occurrence of a “trembling trade” even if trade is quadruply gainful. The example in this section rests on several simplifying assumptions, especially the strong assumption of linearity of the individuals’ utility functions. In the next two sections we present a general modeling framework, and we specify conditions under which a “trembling trade” can occur.

2)This measure of relative deprivation is equivalent to a measure of relative deprivation of individual

III. A THEORY OF A “TREMBLING TRADE”

The setting that we consider is the following. We let P1 and P2 be two populations of size

where the functions  is the vector of the incomes of all the individuals in individual

is the vector of the incomes of all the individuals in individual

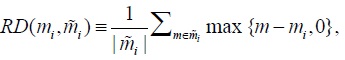

where  denotes the cardinality of the set

denotes the cardinality of the set

We let the individuals in population P1 have pre-trade incomes denoted by

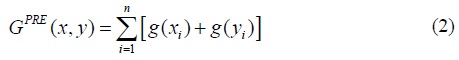

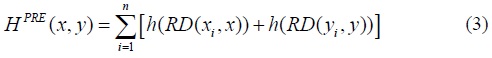

be the sum of the pre-trade levels of utility from income of all the individuals in the two populations, and we let

be the sum of the pre-trade levels of disutility from relative income deprivation of all the individuals in the two populations.

We assume that when trade occurs between populations P1 and P2, the incomes of the members of population P1 represented by the vector

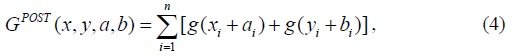

and we let

be, respectively, the sum of the post-trade levels of utility from income and the sum of the post-trade levels of disutility from relative deprivation. From the continuity of the functions

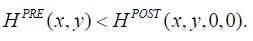

We let  be the pre-trade levels of social welfare of populations P1 and P2, respectively, and we let

be the pre-trade levels of social welfare of populations P1 and P2, respectively, and we let  be the corresponding levels of social welfare of the two populations when trade occurs. Prior to trade, members of each population compare themselves only with members of their own population; the population that they belong to constitutes their exclusive comparison group. When trade occurs, however, members of each population compare themselves also with members of the other population, so that the members of both populations constitute the comparison group of each individual. This revision of the comparison groups arises from the merging of social spheres brought about by trade, as explained in Section 1.

be the corresponding levels of social welfare of the two populations when trade occurs. Prior to trade, members of each population compare themselves only with members of their own population; the population that they belong to constitutes their exclusive comparison group. When trade occurs, however, members of each population compare themselves also with members of the other population, so that the members of both populations constitute the comparison group of each individual. This revision of the comparison groups arises from the merging of social spheres brought about by trade, as explained in Section 1.

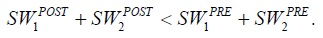

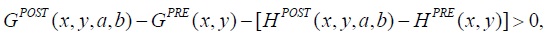

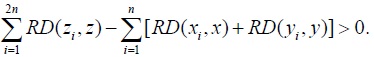

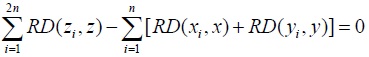

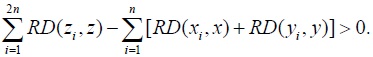

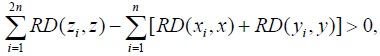

We measure the social welfare of a population in a utilitarian manner, namely as the sum of the utility levels of the members of the population. We study the possible prevalence of a “trembling trade” defined, as already mentioned, as a situation in which the gains from trade are overtaken by the losses in terms of relative deprivation, with the result that global social welfare is reduced. That is, a “trembling trade” arises when

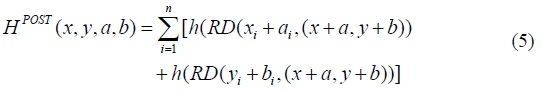

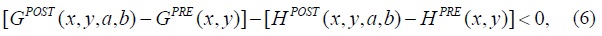

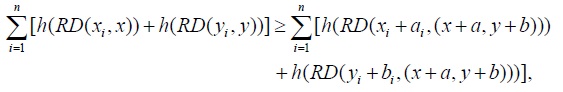

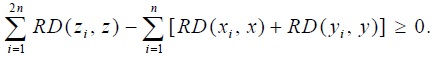

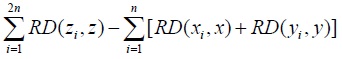

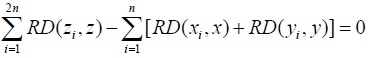

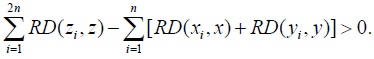

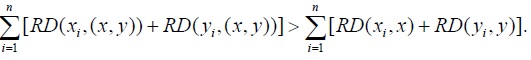

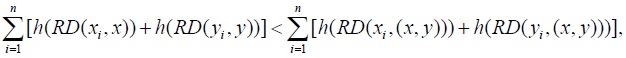

Based on the definitions provided in (2) through (5), we can rewrite this inequality as

which constitutes the necessary and sufficient condition for trade to be trembling. The first bracketed term in (6) represents the aggregate gain from trade that arises from increases in incomes, and the second bracketed term in (6) represents the aggregate loss from trade that arises from the increase in the levels of relative deprivation. The difference between the two bracketed terms is the change in global social welfare.

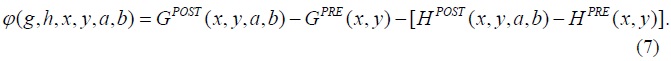

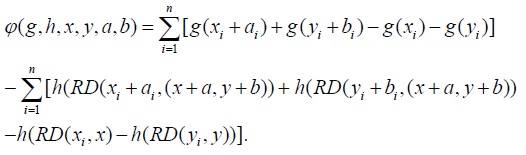

We next define an auxiliary function

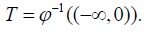

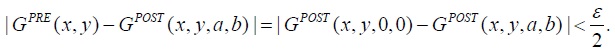

Because a fixed 6-tuple (

We now state and prove four lemmas that in combination provide a basis for subsequently stating and proving our main proposition and corollaries.

The meaning of Lemma 3 is that if only

We now have in place the infrastructure required to present the main result of this section: the occurrence of a “trembling trade” is not singular in the space of the parameters of the model (namely the admissible initial incomes, the gains from trade, and the utility functions of the individuals): a “trembling trade” occurs for an open set in this space. In particular, trade is trembling if the initial income vectors of populations P1 and P2 are not identical, the function

3)The findings reported in this section and in Section 4 do not depend on the assumption that populations P1 and P2 are of equal size. Making this assumption simplifies the notation, eases the proofs, and allows us to focus on the qualitative aspects of our model.

4)Most of the results that follow can be generalized to the case of perfectly heterogeneous populations: the assumption that the functions

5)The vectors

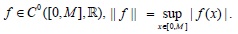

6)Although this assumption is made purely for technical reasons (so that the supremum norm on the space

7)This is the topology given by the supremum norm: for

IV. THE CASE OF QUADRUPLY GAINFUL TRADE

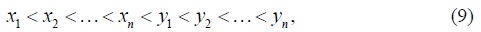

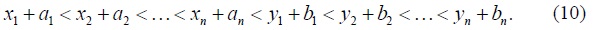

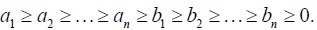

To the “trade” model of the preceding section we now add two assumptions: the individuals in population P1 are poorer than the individuals in population P2, and trade does not affect the ordering of the incomes in the merged population. While the first assumption is innocuous, making the second assumption requires commentary. Having the ordering reserved guarantees that population P1 stays poorer than population P2 also when trade occurs. In addition, the changes in relative deprivation (as defined in Section 2) are then smooth, which simplifies the notation without loss of generality. In addition, making the second assumption is appropriate when considering a short period of time after introducing trade, so that incomes did not change rapidly enough to interfere with the ordering of incomes. And finally, both assumptions are in line with the motivating example of Section 2. Formally, we present these two assumptions, respectively, by

and

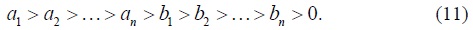

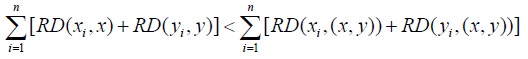

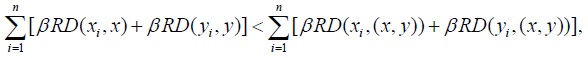

We say that trade between population P1 and population P2 is quadruply gainful if the following conditions hold:

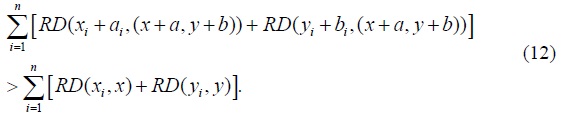

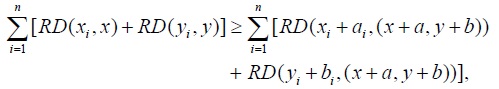

A trade of the type described by (11) raises the incomes of all the individuals in the two populations, narrows the income gaps between the individuals in population P1, narrows the income gaps between the individuals in population P2, and narrows the income gap between population P2 and population P1. Thus, when trade occurs that satisfies (11), the income inequalities in populations

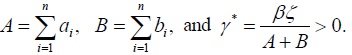

where

where

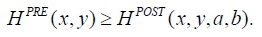

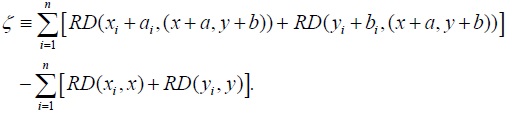

Under which conditions is a quadruply gainful trade trembling? We let

From Proposition 1, it follows that the following holds true.

Thus, (

Drawing on Proposition 1 and Corollary 1, it can be shown that for any set of utility functions of type (1), where (

Let (

We formalize this statement in the next corollary.

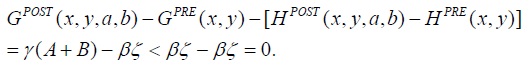

and by the linearity of

which is equivalent to saying that

However,

which contradicts (6). Therefore, such a trade is not trembling, and (

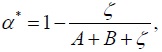

Second, we assume that condition (12) is satisfied. We then define

From the definition of  We now choose

We now choose

for

Thus, (6) is satisfied, and trade is trembling for the parameters (

In the simple case in which

for some

If (12) is satisfied, then we only need to replicate the second part of the proof of Corollary 3 for  and if

and if

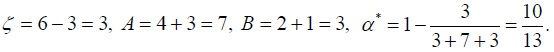

In the example presented in Section 2, namely for initial incomes  and applying the notation from the proofs of Corollaries 3 and 4, we get that

and applying the notation from the proofs of Corollaries 3 and 4, we get that  By Corollary 4, for

By Corollary 4, for  trade is trembling.

trade is trembling.

Having said that, it is helpful to refer again to the example presented in Section 2 in order to somewhat dispel the doubts. Trade in that example is quadruply gainful and is trembling, and the gains from trade are far from tiny: the income of every individual increases by at least 8.3% (in the case of the richest individual), the income of the poorest individual increases by 200%. At the same time, according to our calculations, more than 20% of the space of utility functions satisfying (13) (measured by the parameter

8) also holds true for each

also holds true for each  that belongs to a sufficiently close neighborhood of (

that belongs to a sufficiently close neighborhood of (

V. CONCLUSION

Trade that increases the incomes of the members of the trading populations and reduces the income gaps between and within populations can intuitively be considered to be gainful. However, we showed that even under very favorable assumptions as given by a quadruply gainful trade, it is possible that when trade occurs global social welfare may not improve. Acknowledging that individuals take into consideration not only the comfort of absolute income but also the discomfort of low relative income, we noted that the dismay brought about from expansion of the social space of the members of the trading populations can override the gains from trade. This finding could help explain anti-trade sentiments among populations that engage in a seemingly advantageous trade. For example, Nguyen (2015) argues that concern for inequality is an important factor of the decreasing support for liberal trade policies in the American public, and that, in general, individuals who are more concerned about income inequality are more likely to support protectionist measures. Burgoon (2013) finds that income inequalities encourage support for political parties with protectionist and antiglobalist agendas in OECD countries. Consequently, as Marktanner and Sayour (2009) show, countries characterized by higher levels of income inequality are less likely to liberalize trade as they perceive trade to exacerbate inequality. Distaste for low relative income may also be a reason why Scheve and Slaughter (2006) find that anti-trade sentiments are stronger in countries with higher unemployment rates. On the other hand, in developing countries (for example, in the Philippines, as pointed out by Pasadilla and Liao, 2005), even the wealthiest may be concerned about income comparisons with potential trade partners abroad and, therefore, they oppose unrestricted trade.

Our analysis bears significantly on policy design because it implies that often-prescribed policy recommendations aimed at redressing a downside of trade can well fall short. To see this vividly, we refer to a May 2018 interview of the

In closing, it is tempting to ponder what the social welfare fallout would be from a situation in which a relatively poor economy that geographically neighbors a richer economy but trade-wise is detached from the richer economy, embarks on full blown trade with the richer economy. The perspective elaborated in this paper can serve as a warning sign of a possible adverse outcome.

9)

Tables & Figures

APPENDIX: PROOFS OF LEMMAS 1-4

Proof of Lemma 1.

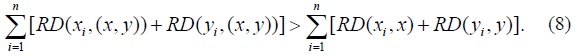

From Stark (2013, Claim 1), we know that if two populations merge while the incomes of their members remain unchanged, then the sum of the post-merger levels of relative deprivation of the individuals who belong to these populations is not lower than the sum of the pre-merger levels of relative deprivation of the same individuals. Thus, for inequality (8) to hold strictly, we only need to prove that equality does not occur if

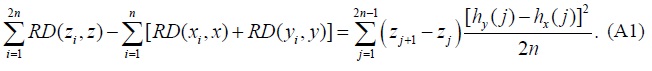

We use the following result from Stark (2013, Proof of Claim 1, p. 7) for populations P1 and P2 of equal size

Each of the summands on the right-hand side of (A1) is non-negative and, therefore,  In order for

In order for  to be equal to zero, all the summands on the right-hand side of (A1) need to be equal to zero. Hence, for each

to be equal to zero, all the summands on the right-hand side of (A1) need to be equal to zero. Hence, for each

Let us assume that  and based on our earlier assumptions, we have that

and based on our earlier assumptions, we have that

I.

Then, for

II.

Then,

III. 0 <

Then,  it is necessary that

it is necessary that

Each of the three cases I, II, and III thus leads to a contradiction. Therefore, when populations P1 and P2 are not identical with respect to their vectors of incomes then, indeed,  which is equivalent to stating that

which is equivalent to stating that  Q.E.D.

Q.E.D.

Proof of Lemma 2.

Using the definitions of

Because the functions

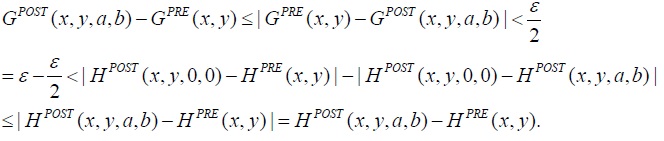

Proof of Lemma 3.

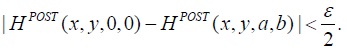

We fix

In particular,

At the same time, because of the continuity of

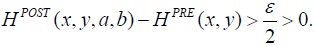

Therefore, there exists

Thus, (6) is satisfied, trade is trembling, and (

Proof of Lemma 4.

We let

and, consequently,

which is equivalent to

and, thus,

Therefore,

Appendix Tables & Figures

References

-

Amiti, M. and J. Konings. 2007. “Trade Liberalization, Intermediate Inputs, and Productivity: Evidence from Indonesia,”

American Economic Review , vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 1611-1638.

-

Antràs, P., de Gortari, A. and O. Itskhoki. 2017. “Globalization, Inequality and Welfare,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 108, pp. 387-412.

-

Barro, R. J. 2000. “Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries,”

Journal of Economic Growth , vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 5-32.

-

Beckfield, J. 2009. “Remapping Inequality in Europe: The Net Effect of Regional Integration on Total Income Inequality in the European Union,”

International Journal of Comparative Sociology , vol. 50, nos. 5-6, pp. 486-509.

-

Berman, E., Bound, J. and S. Machin. 1998. “Implications of Skill-Biased Technological Change: International Evidence,”

Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 1245-1279.

-

Bernhofen, D. and J. Brown. 2005. “An Empirical Assessment of the Comparative Advantage Gains from Trade: Evidence from Japan,”

American Economic Review , vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 208-225.

-

Burgoon, B. 2013. “Inequality and Anti-Globalization Backlash by Political Parties,”

European Union Politics , vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 408-435.

- Burstein, A. and J. Vogel. 2011. Factor Prices and International Trade: A Unifying Perspective. NBER Working Paper, no. 16904.

-

Calderón, C. and A. Chong. 2001. “External Sector and Income Inequality in Interdependent Economies Using a Dynamic Panel Data Approach,”

Economics Letters , vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 225-231.

-

Etkes, H. and A. Zimring. 2015. “When Trade Stops: Lessons from the Gaza Blockade 2007-2010,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 16-27. -

Feenstra, R. C. and G. H. Gordon. 1997. “Foreign Direct Investment and Relative Wages: Evidence from Mexico’s Maquiladoras,”

Journal of International Economics , vol. 42, nos. 3-4, pp. 371-393.

-

Goldberg, P. K., Khandelwal, A. K., Pavcnik, N. and P. Topalova. 2010. “Imported Intermediate Inputs and Domestic Product Growth: Evidence from India,”

Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 125, no. 4, pp. 1727-1767.

-

Goldberg, P. K. and N. Pavcnik. 2007. “Distributional Effects of Globalization in Developing Countries,”

Journal of Economic Literature , vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 39-82.

-

Golub, S. S. and C.-T. Hsieh. 2000. “Classical Ricardian Theory of Comparative Advantage Revisited,”

Review of International Economics , vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 221-234. -

Grossman, G. M. and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2008. “Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring,”

American Economic Review , vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 1978-1997.

-

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., and S. R. Yeaple. 2004. “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms,”

American Economic Review , vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 300-316.

-

Irwin, D. A. 2005. “The Welfare Cost of Autarky: Evidence from the Jeffersonian Trade Embargo, 1807-09,”

Review of International Economics , vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 631-645.

-

Lundberg, M. and L. Squire. 2003. “The Simultaneous Evolution of Growth and Inequality,”

Economic Journal , vol. 113, no. 487, pp. 326-344.

-

MacDougall, G. D. A. 1951. “British and American Exports: A Study Suggested by the Theory of Comparative Costs. Part I,”

Economic Journal , vol. 61, no. 244, pp. 697-724.

-

MacDougall, G. D. A. 1952. “British and American exports: A Study Suggested by the Theory of Comparative Costs. Part II,”

Economic Journal , vol. 62, no. 247, pp. 487-521.

-

Marktanner, M. and N. Sayour. 2009. “Does Initial Inequality Prevent Trade Development? A Political-Economy Approach,”

Trade and Development Review , vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 93-105. -

Melitz, M. J. 2003. “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity,”

Econometrica , vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 1695-1725.

- Nguyen, Q. 2015. “Mind the Gap”: Inequality Aversion and Mass Support for Protectionism. NCCR Trade Regulation Working Paper, no. 2015/19.

-

Ohlin, B. 1933.

Interregional and International Trade . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. -

Pasadilla, G. M. and C. M. M. Liao. 2005. “Who Are Opposed to Free Trade in the Philippines?”

Philippine Journal of Development , vol. 32. no. 1, pp. 1-17. -

Ricardo, D. 1817.

On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation . London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street. -

Sampson, T. 2014. “Selection into Trade and Wage Inequality,”

American Economic Journal: Microeconomics , vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 157-202.

-

Scheve, K. and M. J. Matthew. 2006. “Public Opinion, International Economic Integration, and the Welfare State,” In Bardhan, P., Bowles, S. and M. Wallerstein. (eds.)

Globalization and Egalitarian Redistribution . Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 217-260. -

Stark, O. 2013. “Stressful Integration,”

European Economic Review , vol. 63, pp. 1-9.

-

Stark, O. and J. Wlodarczyk. 2015. “European Monetary Integration and Aggregate Relative Deprivation: The Dull Side of the Shiny Euro,”

Economics and Politics , vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 185-203.

-

Stark, O., Zawojska, E., Kohler, W. and K. Szczygielski. 2018. “An Adverse Social Welfare Effect of A Doubly Gainful Trade,”

Journal of Development Economics , vol. 135, pp. 77-84.

-

Stolper, W. and P. A. Samuelson. 1941. “Protection and Real Wages,”

Review of Economic Studies , vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 58-73.