- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 26, No. 1, 2022. pp. 27-48.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2022.26.1.404

Number of citation : 3Rise of Geopolitics and Changing Korea and Japan Trade Politics

|

Ewha Womans University |

|

|

Ewha Womans University |

Abstract

In the past decade, Korea and Japan have increasingly exhibited different strategic priorities in trade in face of China’s rising global economic prowess and worsening US-China trade conflict. Japan’s trade policy decisions have worked to reinforce its economic and security ties with the US as a means to counter China. Japan has used both bilateral and multilateral means to secure its ties with the US against China. In contrast, Korea’s trade policy positions have been one of ‘strategic ambiguity’. Korea has been more conciliatory towards China, reluctant to take actions that would counter China’s interest. Korea has mainly resorted to bilateral channels to maintain favorable relations with both China and the US. Korea’s reluctance to clearly ally with the US against China has been observed across different administrations with opposing political orientations. This paper examines Korea and Japan’s diverging strategic priorities in trade through the 2017 World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference; the 2017 US imposition of Section 232 on steel; the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Korea-US FTA renegotiation and the Korea-China FTA Phase Two Negotiation; and the 2019 Japan-US Trade Agreement.

JEL Classification: F50, F51, F53

Keywords

Korea, Japan, geopolitics, trade, trade conflict

I. Introduction

Since the late 1990s, Korea and Japan have managed to sign high-level free trade agreements (FTAs) that have significantly expanded the scope and deepened the depth of trade liberalization. By the end of 2021, Korea signed 18 FTAs with trade partners that account for 77 percent of Korea’s total trade in 2021 (Korea International Trade Association, 2021). Similarly, Japan signed 21 FTAs with trade partners that account for 86 percent of Japan’s total trade in 2021 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2022).1 FTA expansion came at different times for the two countries. Korea’s major spurt of FTA expansion came during the late 1990s to the end of 2012, when the Korean government ambitiously signed high-level FTAs with major trade partners such as the United States (US) and the European Union. Japan’s FTA expansion started more than a decade later in 2013, when the Japanese government joined the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiation (TPP).2 In these high-level FTAs, Korea and Japan agreed to significant tariff concessions on historically protected sectors such as agriculture (Choi and Oh, 2021: 2-3). In the past two decades, both countries have used FTAs to deepen trade relations with major trade partners, albeit in different time periods.

The abundance of FTAs signed by Korea and Japan hide growing differences underlying the two countries’ strategic priorities in trade. In the past decade, Korea and Japan have increasingly exhibited different strategic priorities in trade in face of China’s rising global economic prowess and worsening US-China trade conflict. Japan’s trade policy decisions have worked to reinforce its economic and security ties with the US as a means to counter China. Japan has used both bilateral and multilateral means to secure its ties with the US against China. In contrast, Korea’s trade policy positions have been one of ‘strategic ambiguity’. Korea has been more conciliatory towards China, reluctant to take actions that would counter China’s interest. Korea has mainly resorted to bilateral channels to maintain favorable relations with both China and the US. Korea’s reluctance to clearly ally with the US against China has been observed across different administrations with opposing political orientations. In other words, the political orientations of the government has not had a huge impact in shaping Korea’s strategic priorities in trade.

This paper examines Korea and Japan’s diverging strategic priorities in trade through major instances of trade agreements, disputes and forums. Specifically, the paper examines the following five cases: the 2017 World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conference; the 2017 US imposition of Section 232 on steel imports; the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); the Korea-US FTA (KORUS FTA) renegotiation and the Korea-China FTA Phase Two Negotiation; and the 2019 Japan-US Trade Agreement. These five cases demonstrate that changing geopolitical conditions have altered the strategic priorities of Korea and Japan on trade, setting them on diverging paths as early as 2013. The findings have broader geopolitical significance. Korea and Japan have been traditional economic and security allies of the US in East Asia, taking part in upholding the liberal hegemony of the US in the East Asian region. Korea’s shifting strategic priorities in favor of China reflects potential changes to Korea’s trade relations with the US and to its East Asian neighbors such as Japan. More broadly, Korea’s reluctance to side with the US against China signals a potential unraveling of traditional economic and security ties that have governed East Asia for much of the post-World War II period.

The paper is organized as follows. Section II overviews the literature on the nexus between geopolitics and trade politics. Section III provides a background on the rise of China’s economy and the US-China trade conflict. Section IV analyzes the diverging foreign economic priorities of Korea and Japan through five short cases. Section V concludes with a perspective on the future course of Korea and Japan’s trade politics.

1)Calculated by the author.

2)See chapter 2 of

II. Understanding East Asian FTA Politics within a Geopolitical Context

Geopolitical conditions have not factored largely in studies of East Asian FTAs. The largest reason being that geopolitical conditions shaping the East Asian regional order has been largely stable for over half a century in the post-World War II period. As Ikenberry (2004: 353) notes, “the most basic reality of postwar East Asian order has stayed remarkably fixed and enduring—namely, the American-led system of bilateral security ties with Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and countries to the South.” At the same time, Ikenberry (2004: 354) recognized that East Asian states “increasingly expect their future economic relations to be tied to China.” When East Asian states first embarked on FTAs in the late 1990s, the US still had a dominant presence in the region and also in the global trade order, albeit a weakening influence. China had not yet joined the WTO, but was clearly on its path to become a major trade partner of the East Asian states. There were signs, however, of grave challenges to the existing liberal global economic order such as the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 and the stalling of the WTO’s Doha Round negotiations. The absence of multilateral trade liberalization efforts propelled the East Asian states such as Korea and Japan to turn to FTAs as a means to further promote trade (Choi, 2018b: 83-115).

In the relatively more stable geopolitical conditions of the late 1990s and 2000s, some viewed FTAs as a stepping stone to achieve broader trade liberalization, deeper economic integration at the global level, and strengthened competitiveness of domestic industries (Ravenhill, 2017: 165). In this light, East Asian FTAs contributed to positively linking East Asian economies to the liberal global economy (Choi, 2018b: 113-115). In fact, high-level FTAs such as the Korea-US FTA (KORUS FTA), the Korea-EU FTA, and the CPTPP have opened up highly protected sectors such as agriculture.

FTAs can also be viewed as contributing to regional security and peace in East Asia. Growing economic interdependence among East Asian states and with major trade partners in the west could serve to contain political tension from escalating. East Asian states would be reluctant to take political actions that could disrupt trade if they were deeply linked to the global trade system. For example, in the early 2000s when Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi worsened political relations with China by visiting the controversial Yasukuni Shrine every year, economic ties between Japan and China did not weaken. In fact, Davis and Meunier (2011: 640) observe that “the economic relationship between Japan and China became increasingly interdependent over the same period that political relations worsened. Japanese trade with China has grown steadily.” Sohn (2019: 1020) aptly depicts the economic and security relationship in East Asia for much of the postwar period as a “positive nexus”, in which there were “virtuous spillover effects between security and economic relations.” Overtime, the positive nexus “created a positive feedback loop feeding stable and prosperous interstate relations across the region” (Sohn, 2019: 1020).

In the past decade, however, geopolitical conditions have changed dramatically. Foremost, China has assumed the position of a global economic power and wields economic influence across the East Asian region. China has surpassed the US as the largest trade partner of Korea and Japan.3 The US and China have also been deeply embroiled in trade conflicts since 2016, with no signs of imminent resolution. Scholars have begun to ask whether the rise of China will fundamentally alter the liberal hegemony of the US and ultimately trade politics in East Asia. Ikenberry (2016: 10) describes the current geopolitical condition as a “dual hierarchy” where the US dominates the security hierarchy and China dominates the economic hierarchy. He predicts that middle states such as Korea and Japan will have a strong interest in maintaining the dual hierarchy and use a mixture of engagement and hedging strategies to maintain ties with both the US and China without escalating conflicts (Ikenberry, 2016: 34-40). Sohn (2019: 1021) observes that Japan and China have already entered a “negative nexus” in their economic and security relations when worsening bilateral political relations due to the Senkaku island disputes that led to a halt in Chinese exports to Japan of rare earth minerals. Sohn (2019: 1021) further observes that Korea is placed in a predicament: it has to “accommodate [China] while at the same time courting US engagement in resolving the North Korean nuclear problems.”

The newly emerging and ongoing studies on geopolitics and East Asian trade politics echo the view that the rise of China and the escalating US-China trade conflict pose a dilemma for the East Asian states. Will they maintain their security ties with the US while deepening economic dependence on China? This paper hopes to further build on the literature by arguing that while Japan has already taken a clear stance on the US-China rivalry through their trade positions, Korea has adopted a position of strategic ambiguity. As early as 2013, Japan clearly signaled its willingness to reinforce its economic and security ties with the US to counter China when it joined the TPP negotiations. During his speech to the US Congress in 2015, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan proclaimed:

“Involving countries in Asia-Pacific whose backgrounds vary, the U.S. and Japan must take the lead. We must take the lead to build a market that is fair, dynamic, sustainable, and is also free from the arbitrary intentions of any nation…we can spread our shared values around the world and have them take root: the rule of law, democracy, and freedom. That is exactly what the TPP is all about. Furthermore, the TPP goes far beyond just economic benefits. It is also about our security.”4

In the mindset of the Japanese power elites, the TPP was, in essence, the US-Japan economic and security alliance (Choi, 2018b: 126). Korea signaled its reluctance to counter China when it hesitated to join the TPP negotiations. Although Korea was in a relatively favorable position compared to Japan in terms of FTAs—for example Korea already had FTAs with major trade partners such as the US and the EU—Korea’s consideration of China was the main reason for staying out of the TPP negotiations. This issue is discussed more carefully in section IV. Since then, Korea and Japan have demonstrated their diverging strategic priorities concerning China and the US in various trade issues as examined in section IV.

3)World Integrated Trade Solution,

4)

III. Rise of China and Changing US Trade Position on China

1. China’s Economic Rise and Changing Trade Relations in East Asia

China has enjoyed phenomenal economic growth in the past two decades. China’s GDP has grown at an average annual rate of over 10 percent in the first decade of the 2000s and an average annual rate of 7.7 percent from 2010 to 2019 (The World Bank, 2022). China’s GDP per capita (current price US$) increased from US$959.4 in 2000 to US$10,143.8 in 2019. The total value of trade (current price US$) also grew exponentially during this time period. Total exports in goods and services (current price US$) rose form US$253.1 billion in 2000 to US$ 2.63 trillion in 2019. Similarly, total imports in goods and services (current price US$) rose from US$ 224.3 billion to US$2.5 trillion in the same time period. In 2019, China had the second largest GDP (current price US$) in the world after the US at US$14.3 trillion (The World Bank, 2022).5

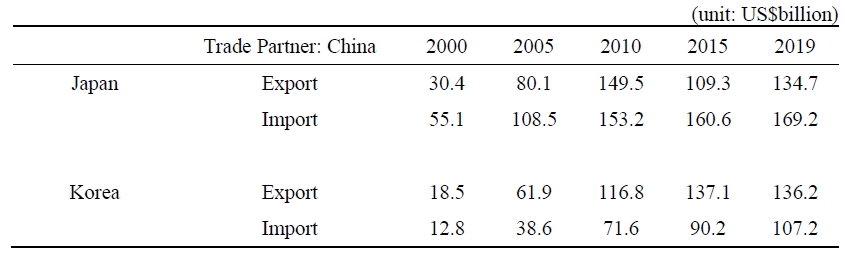

China’s economic rise has significantly altered trade patterns in East Asia. In both Korea and Japan, China has surpassed the US as the largest trade partner. In Korea, total exports to China (excluding Hong Kong) has increased from US$18.5 billion in 2000 to US$136.2 billion in 2019 (Table 1). During this time, total imports from China (excluding Hong Kong) into Korea rose from US$12.8 billion to US$107.2 billion. In 2019, China accounted for 25.1 percent of Korea’s total exports and 21.3 percent of total imports. The US lagged far behind, accounting for 13.6 percent of Korea’s total exports and 12.34 percent of Korea’s total imports.6

Likewise, Japan’s total exports to China rose from US$30.4 billion in 2000 to US$134.7 billion in 2019 (Table 1). Total imports from China rose from US$55.1 billion to US$169.2 billion in the same time period. China was Japan’s largest export and import partner in 2018. In 2019, Japan’s exports to China declined slightly, making the US Japan’s largest export partner by a small margin. Both China and the US each respectively accounted for about 19.1 and 19.9 percent of Japan’s exports. China, however, continued to be Japan’s largest import partner, accounting for 23.5 percent of Japan’s total imports in 2019. The US followed in far second, accounting for 11.3 percent of Japan’s imports in 2019.7

In the past two decades, China, Korea and Japan have strengthened their economic interdependence in terms of trade. From China’s viewpoint, Japan and Korea are its top trade partners. In 2019, Japan and Korea were respectively China’s third and fourth largest export partners. Korea and Japan were also respectively the first and third largest import partners of China.8 Given their strong economic ties with China, Korea and Japan faced similar predicament when their traditional security ally, the US, engaged in a full front trade confrontation with China in 2017.

2. Donald Trump Administration and the US-China Trade Conflict

In 2017, US trade relations with China sharply deteriorated under the newly inaugurated President Donald Trump’s administration. Previous US administrations had held a relatively positive view of China’s rapid economic growth and accession to the WTO. China’s blooming economy, market opening, and growing trade were seen as critical factors linking China to the liberal global economy. The expectation was that China would have a greater stake in maintaining international stability and order since it was deeply integrated in the global trade order (Pempel, 2019: 998). In stark contrast, President Trump held a mercantilist view towards China’s economic rise. President Trump criticized the trade imbalance between the US and China, pointing to the growing US trade deficit with China. In 2010, US trade deficits with China was about US$273 billion (nominal). This figure grew to about US$347 billion in 2016 when President Trump was campaigning for his presidential election and reached a peak at US$418 billion in 2018 (US Census Bureau, 2022). President Trump politicized the issue of growing US-China trade deficit during his election campaign, promoting his vision of ‘America First’. In particular, President Trump blamed China’s unfair trade practices for the growing trade imbalance between the US and China. Specifically, the US blamed China for implementing market-distorting industrial policies that gave its state-owned enterprises a competitive edge in the global market. China was also accused of engaging in protectionist practices against foreign products, including US products (Kwan, 2019: 3-4).

Once he came into office, President Trump immediately took actions against China. Kwan notes that President Trump’s administration:

“shifted its China policy form engagement to decoupling…decoupling aims to prevent China from threatening US leadership in the world by constraining China’s behavior and economic growth through such measures as raising import tariffs on Chinese products, restricting exports of high tech-products to China and strengthening the restrictions on direct investments in the USA by Chinese companies.”9

In 2017, the US Department of Commerce initiated Section 232 investigation on steel and aluminum imports, setting high tariffs on Chinese aluminum and steel products. In 2018, President Trump’s administration administered about “$60 billion worth of tariffs on targeted Chinese imports” and “some additional $200 billion in additional tariffs on Chinese goods” in 2019 (Pempel, 2019: 1002). These hostile actions were of course retaliated in kind by the Chinese government, which imposed tariffs on US goods such as automobiles and farm goods. Within a short period of time, a ‘tit-for-tat’ escalation of tariff hike between the US and China exploded into a trade war between the two largest economies in the world.

Worsening US-China trade conflict inevitably has posed a challenge for Korea and Japan. For both countries, the US is a traditional security ally and China is their most important trade partner. Interestingly, Korea and Japan have exhibited diverging strategic priorities; Japan has reinforced its ties with the US to counter China, whereas Korea has avoided taking actions that could antagonize China. Such diverging priorities are observable in Korea and Japan’s positions on major trade issues that have involved the US and/or China. The following section examines the diverging strategic priorities of Korea and Japan through five trade cases.

5)All data in the section use 2019 as the end year to avoid including data during the Covid-19 period.

6)World Integrated Trade Solution,

7)Ibid.

8)Ibid.

9)

IV. Diverging Strategic Priorities of Korea and Japan on Trade

1. 2017 11th WTO Ministerial Conference

The 2017 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires served to be the first major instance of Korea and Japan signaling their diverging strategic trade priorities in a multilateral trade forum. From the onset, the US was highly critical of China and other emerging economies such as India. In his opening plenary statement, the US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer warned that, “We cannot sustain a situation in which new rules can only apply to the few, and that others will be given a pass in the name of self-proclaimed development status” (Office of the US Trade Representative [USTR], 2017b). There was no doubt that China was included in the “others” that “proclaimed development status”.

During this conference, Japan formally joined a trilateral agreement with the US and the EU to denounce unfair trade practices and commit to a “global level playing field” (USTR, 2017a). The US, EU and Japan issued a joint statement denouncing “government-financed and supported capacity expansion, unfair competitive conditions caused by large market-distorting subsidies and state-owned enterprises, forced technology transfer, and local content requirements and preferences” (USTR, 2017a).

Interestingly, Korea was not part of the trilateral agreement although it had reasons to be critical of China. The 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference came at a time when China was imposing trade retaliations on Korea in response to the 2016 Korean government’s decision to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD, anti-North Korean missile defense system) system. China’s trade retaliations had immediate detrimental effects on selective retail companies (in particular Lotte Group) and on tourist and entertainment industries. For example, Lotte Mart in China faced regulatory interventions that made store operation difficult, eventually resulting in the full withdrawal of Lotte Mart from China in 2018. Chinese tourists-who accounted for 47 percent of all tourists arrivals in Korea in 2016—dropped drastically. Some estimate about $15.6 billion in lost revenue in the tourism industry and related industries in retail and hospitality due to the reduction in Chinese tourists (Lim et al., 2020: 928). The Korean government, however, was reluctant to take actions that would aggravate China at a time when China was imposing trade retaliations. The absence of Korea in the trilateral agreement is significant because it marked Korea’s strategic priorities towards the US and China in subsequent trade issues. Korea would not take trade actions that would be deemed as hostile towards China. Instead, Korea would try to resort to bilateral channels to maintain friendly ties with both trade partners.

2. Section 232 on Steel

In March 2018, President Trump’s administration imposed a 25 percent tariff on select steel products in response to the US Department of Commerce’s Section 232 investigation on steel imports.10 These tariffs targeted not only China, but other major steel exporters to the US such as the EU, Korea and Japan. In 2016 and 2017, Korea and Japan were among the top ten exporters of steel to the U.S. and keenly felt the adverse impacts of the tariffs (Choi and Oh, 2021: 107).

Korea and Japan took diverging approaches to the steel tariffs. Korea resorted to a bilateral dialogue with the US, whereas Japan sought to cooperatively work with other major trade partners to engage in a multilateral response to the US. Korea agreed to a voluntary export restraint on steel with the US. Under the arrangement, the US would waive the 25 percent tariff on Korean steel imports and Korea would export up to the agreed import quota of 2.63 million ton for a year, which accounts for 70 percent of Korea’s average export volume over the past three years. Korea was the third-largest exporter of steel to the US along with Canada (16.1 percent) and Brazil (13 percent), accounting for 10.2 percent of total steel imports of the US in 2017 (Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency [KOTRA], 2017).

Korea and Japan’s diverging responses to the US imposition of Section 232 on steel reflect Korea's increasing tendency to opt for a bilateral route in resolving trade issues as opposed to Japan's preference to opt for the multilateral route. Other major steel exporting countries to the US viewed the US’s unilateral imposition of steel tariffs under the Section 232 as undermining and violating the multilateral trading rule. Accordingly, Canada, Mexico, and the EU brought their complaints to the WTO dispute settlement (KOTRA, 2017). Korea could have aligned with the EU, Canada, Japan and other economies to protest the unreasonable and unilateral aspect of Section 232. Yet Korea chose not to do so. This decision is not insignificant since it foreshadowed Korea’s increasing unwillingness to cooperate with major trade partners such as Japan and the EU in the multilateral arena on major trade issues. While the strategy worked in the short run for Korea, in the long run, the implication is that Korea is increasingly more isolated. Korea did not cooperate with Japan and the EU during the 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference, and once again with Section 232 on steel, Korea did not cooperate with either of them.

3. CPTPP

The diverging strategic priorities of Korea and Japan are most apparent in their approach to the TPP/CPTPP. The TPP was the US government’s trade initiative to newly write the trade rules for the 21st century as a counter to China’s growing economic dominance. The TPP would be an economic alliance among twelve likeminded countries11 that would further cooperate in the Asia-Pacific region to promote the liberal global trade order (The White House-President Barack Obama, n.d.). As such, the TPP served US economic and geopolitical goals. However, in a drastic turn around, President Trump withdrew US from the TPP immediately after coming into office. Despite the withdrawal of the US, the remaining 11 negotiating countries of the TPP agreed to salvage the agreement and signed the CPTPP. Throughout the entire process leading up to the CPTPP, Korea was hesitant to join, whereas Japan joined the TPP negotiations and even played the leadership role after the US withdrawal (Terada, 2019).

In the early years of the TPP negotiations, Korea did not join the TPP, whereas Japan joined the negotiations in 2013. Korea did not see strong gains from the TPP since it already had an FTA with the US and with other major trade partners such as the EU. The Korean government also faced strong opposition to the TPP from the automobile sector, which feared competition from Japanese automobile companies in the domestic market (Choi and Oh, 2021: 48). In addition to these more economic considerations, China’s antagonistic stance towards the TPP played an equal if not greater role in the Korean government’s decision to stay out of the TPP. China accused the TPP as a conspiracy to block China’s rise. The accusation was not farfetched. In fact, President Barack Obama stated that the “TPP allows America ? and not countries like China ? to write the rules of the road in the 21st century, which is especially important in a region as dynamic as the Asia-Pacific.”12 In the mindset of the Korean policy makers, China was a critical link in resolving the security dilemma caused by the nucleararmed North Korea. By not joining the TPP, Seoul wanted to send a signal to Beijing that Korea wanted to have favorable relations with China (Choi and Oh, 2021: 65). Korea was also in the middle of negotiating an FTA with China, which created further incentives not to take actions that would antagonize China. In sum, Korea’s reluctance to antagonize China was an important reason behind its decision not to join the TPP negotiations. As is demonstrated in the next case examination on the Korea-China FTA, however, Korea’s conciliatory approach to China ultimately did not serve Korea’s interest.

In contrast, Japan envisioned the TPP as a critical strategy to reinforce its ties with the US and counter the rise of China. Joining the TPP was a top priority of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe when he formed his government in 2013. Prime Minister Abe (2015) threw his political capital in negotiating the TPP as strategic tool to strengthen US-Japan economic and security alliance to contain the rise of assertive China. Japan’s decision to negotiate the TPP was also a game-changer in the FTA race between Korea and Japan. When Korea was pursuing high-level FTA with the US and the EU from the late 1990s to 2012, Japan failed to conclude high-level FTAs. Japanese companies were at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their Korean counterparts in the US and EU markets due to trade diversion. Japan’s joining the TPP would help mitigate such trade diversion.

Once the TPP deal was concluded in 2015, the Korean government was under acute criticism. The Korean business sector and the public accused the government of being a mere spectator to the largest trade agreement. During her visit to the US in October 2015, President Park Geun-hye indicated that Korea was a “natural partner” in TPP, considering that Korea had FTAs with all but two of the TPP members (Lee, 2015). She never delivered on this statement as she was impeached in 2017. Under the subsequent President Moon Jae-in’s administration, the government had ample opportunity to join the CPTPP. However, the Korean government was divided between the pro-CPTPP and anti-CPTPP group. Economically, the CPTPP posed a threat to Korea’s agricultural sector. The CPTPP entails high levels of market openness to agricultural powerhouses such as Chile, Canada, Vietnam, and Australia. The economic cost, however, was not the main reason behind Korea not joining the CPTPP. The Korean government’s hesitation to join the CPTPP has been more political in nature. Joining the CPTPP could raise political tensions with China. And the Korean government has consistently adopted a position of strategic ambiguity between the US and China.

In an interesting turn of event, China applied to seek membership in the CPTPP on September 2021 (Baschuk and Lee, 2021). The move is rather surprising, since the CPTPP is not designed for China’s state-led economic system. Without a drastic overhaul of its economic system, in particular, in its relationship between the state and the business sector, China’s accession will not be possible. Considering China’s everheightening control of the private sector, expecting such reforms would be naive and unrealistic (Shelton, 2021). Interestingly, a few weeks after Beijing’s bid to join the CPTPP, the Korean government signaled its interest to also join the CPTPP. The Korean Trade Minister Yeo Han-koo stated, “I think Korea is more than ready and prepared to enter into CPTPP than any other country now” (Baschuk and Lee, 2021). On February 2022, the Korean government stated that it would submit an official application to join CPTPP in April (Koo, 2021).

What can one infer from these sequences of the events? First, the Korean government’s public intention to consider joining the CPTPP very quickly followed China’s bid to join the CPTPP. Although one could argue that the Korean government was concerned about being left out of a trade pact that involved its major trade partners and East Asian neighbors, Korea’s economic incentives should not have changed much. As discussed earlier, China faces enormous hurdles in getting accepted to the CPTPP. What has changed, however, is China’s position on the CPTPP. Moreover, Korea-Japan relation has worsened in recent years compared to the early years of original TPP negotiations. Since 2018, the two countries have seen disputes over the Korean Supreme Court’s rulings on victims of forced labors in Japanese companies during the Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) spill over to trade disputes.13 Clearly, desire to improve relations with Japan was not a huge factor driving Korea’s decision to express willingness to join a trade pact that has been led by Japan. Overall, there are good reasons to believe that China’s shift in stance towards the CPTPP has been an important factor shaping the Korean government’s trade positions on the CPTPP.

4. KORUS FTA Renegotiation and the Korea-China FTA Phase Two Negotiations

Since 2017, Korea had to renegotiate its FTA with the US and also start its phase two FTA negotiations with China on service and investment sectors. In both negotiations, the outcomes were not favorable for Korea. One major reason behind these unfavorable results is that Korea has lost significant clout to influence its trade partners since Korea failed to develop a more comprehensive trade strategy in the midst of intensifying geopolitical rivalry.

The fate of the KORUS FTA, which had been effective since 2012, was suddenly the subject of heated controversy between Washington and Seoul when Donald Trump became the President of the US. During his campaign for the White House, President Trump assailed major US FTAs, mainly the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), KORUS and TPP. President Trump threatened to terminate KORUS if trade imbalance, in particular in the auto sector, was not corrected (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, 2018). The assertive and provocative stance of President Trump did not duly reflect the prevailing consensus among experts and the business sector that the KORUS was mutually beneficial to both countries: Korea enjoyed enhanced market access in manufacturing while the US enjoyed an increase in its export in the service sector (KOTRA, 2017).

While Korea was reluctant to renegotiate the KORUS, the actual negotiation process was rather swift and briefer than expected. An agreement was reached on the amendment and modification of the KORUS FTA in March 2018. The most significant outcome was in the auto sector. The 25 percent tariffs on Korean pick-up trucks, which was scheduled to be terminated in 2021, was delayed to be terminated in 2041. Korea also agreed to exempt vehicle safety standards and relax greenhouse gas regulations for US automakers. The 20 year delay in pick-up truck tariff elimination was detrimental to the Korean auto sector. Pick-up trucks are the most lucrative part of the US auto market, where the US auto makers enjoy virtual dominance under punitively high tariff walls. Under the original KORUS, the Korean auto companies could have exported pick-up trucks to the US without any tariffs from 2021. No other automobile exporting countries to the US have been able to achieve similar outcomes. In TPP, the best Japan could negotiate was 30 years delay for the same tariff elimination. Under the amended KORUS, Korean automobile companies have lost the possibility of entering the US pick-up truck market substantially earlier than their competitors in Japan and EU. The only commercially viable option for Korean automobile companies is to produce pick-up trucks in the US. That would mean a high-paying job creation opportunity in Korea is transferred to the US (Choi, 2018a).

Korea did not fare better in its second phase FTA negotiation with China. When the Korea-China FTA went into effect in December 2015, it was far from complete. The Korea-China FTA was mainly on goods and did not include agreements on service and investment. Nonetheless, the Korean government under President Park Geun-hye hurried to conclude the negotiations. The Korea-China FTA was declared in 2014 at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation’s Economic Leaders Summit that was hosted by President Xi Jinping of China. By all accounts, the abrupt conclusion of the Korea-China FTA was politically driven. Expecting the negative repercussion, negotiators worked on a clause for the second phase negotiation on service and investment.

Considering the rise in Korean investment in China in the context of China’s increasingly protectionist policies (e.g., mandatory technology transfer and discriminatory regulations), the second phase of negotiation on service and investment was imperative for Korea. The second phase negotiation was agreed to resume in two years after the first phase of agreement went into effect. In 2017, however, China was not ready to take a seat at the negotiation table. Korea's decision to deploy the US THADD system in 2016 brought severe political conflict between Seoul and Beijing (Diaz and Zhang, 2017). Korean culture, tourism, and firms in China became the target of Chinese retaliation. In March 2018, Korea and China had the first round of the second phase negotiation of the FTA on the service and investment sectors. From 2018 to 2020, the two countries had nine official rounds of the second phase negotiations.

The talks have not been moving forward. There is a little prospect for an imminent agreement. The fact that Korea and China had an FTA did not prevent China from imposing a unilateral trade retaliation on Korea due to THAAD. For this reason, the strategic benefit of pursuing the second phase of FTA with China has become dubious for Korea. Furthermore, the intensifying power competition between the US and China is driving Korea into an uncharted territory. During the era of China’s ‘peaceful rise’ that did not challenge the US-led international order, Korea enjoyed its security protection under the US, while enhancing and deepening economic ties with China. In this new geopolitical landscape, it is unlikely that China would accord special favor to Korea in the second phase negotiations. The so-called strategic ambiguity of Korea under President Moon Jae-in’s administration—which basically meant that Korea would not take firm stance in choosing a side between the US and China and the government would leave trade issues to the private sector—has failed to secure a deal from China so far. The negotiating goal of Korea is to reduce non-tariff barriers and protect Korean business and assets in China. Korea expects China to lift THAAD retaliations on Korean culture and firms in China. Yet, the likelihood of Korea achieving its goals seems low as Korea has very little leverage over China.

5. 2019 Japan-US Trade Agreement

During President Trump’ administration, Japan also came under tremendous pressure to redress its trade deficit with the US. Japan’s share of the US trade deficit was about seven to 10 percent since the late 2000s (Urata, 2020: 3). As discussed earlier, Japan faced tariffs on its steel due to US imposition of Section 232 on steel imports. Under such circumstances, President Trump’s administration forced Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to start bilateral trade negotiations in the fall of 2018. The Japan-US Trade Agreement resulted in modest levels of trade liberalization, with both parties achieving at least one key agenda.

For the US, obtaining greater access to the agriculture and automobile markets in Japan were key agendas. On Japan’s part, a key agenda was to remove the threat of tariffs on automobile from the US. After six months of negotiations, the Japan-US Trade Agreement concluded, resulting in modest trade liberalization. The commitments covered 5 percent of bilateral trade—specifically “$7.2 billion each of US imports and exports” (Williams et al., 2019). The US reduced or eliminated tariffs on mostly industrial goods while Japan agreed to “reduce or eliminate tariffs on roughly 600 agricultural tariff lines and expand preferential tariff-rate quotas for a limited number of U.S. products” (Williams et al., 2019). The agreement, however, did not include commitments on automobiles, which was a controversial trade issue between the two countries. Overall, each country was able to conclude the negotiation by achieving at least one goal: the US gained greater access to the Japanese agricultural market and Japan stalled threats on its automobile exports. While it is too early to conclude that the relatively benign outcome of the Japan-US Trade Agreement was due to Japan’s strategic alliance with the US, such alliance is likely to play a greater role in shaping the trade positions of the two countries.

10)“Section 232 allows the President to impose import restrictions based on an investigation and affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce that certain imports threaten to impair the national security” (Feber, 2021).

11)The original TPP member states were Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States.

12)

13)For details, see

V. Conclusion

The first two decades of the 21st century have witnessed the intensifying effort of creating trade advantages through bilateral and plurilateral FTAs. As leading manufacturing economies, Korea and Japan have developed FTA strategies to enhance market access to foreign economies and strengthen global value chain for their companies and consumers. After two decades, Korea and Japan find a significant part of their economic activities governed through a network of FTAs. It is striking to note that there is no FTA between Korea and Japan. It is not that Korea and Japan have not imagined the possibility of an FTA between them, but that the Korea-Japan FTA negotiations came to halt after some rounds of talks in 2003. Since then, there were few futile attempts to revive the negotiation. The return of geopolitics in East Asia and concurrent intensifying power competition between the US and China have pushed the trade politics of Korea and Japan further apart. Japan has consistently aligned its stance to the US, while Korea has shown strategic ambiguity.

Will such divergent path of Korea and Japan continue in the future? Unlike President Trump’s administration that resorted to unilateral mercantile policies to counter China, the current President Joe Biden’s administration has indicated that the US will contain China through alliance with like-minded countries that share democratic values (USTR, 2021). President Biden’s administration, however, has not strayed far from its predecessor in terms of its trade policies towards China. President Biden’s administration has maintained tariffs on about $350 billion of Chinese goods (Lobosco, 2022). Furthermore, President Biden now faces the challenge of addressing China’s failure to deliver on its commitments from the U.S.-China Phase One trade agreement (Leonard, 2022). To the US policy makers, Phase One agreement was just a half-way house, since the essence of the Chinese non-market system of uneven level-playing field caused by hefty subsidies and discriminatory measures against foreigners remained intact. The US is also keenly aware of the rapid advance of China in some key digital technology with dual use in business and security such as 5G, AI (Artificial Intelligence), and Quantum Computing (Choi, 2020). The Biden administration is putting efforts to reconfigure and rebuild the global supply chain in key strategic sectors, including semiconductor, battery, pharmaceutical product and rare earth elements. Heavy dependence on China in these key sectors would make the US vulnerable in the economic and security dimensions. In the newly constructed supply chain, the US aims to build a Trans-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific alliance. Under this new strategic blue print, the existing global supply chain that had evolved during the era of China’s peaceful rise would not be sustainable. The question then is whether the trajectory of Korea’s trade positions would converge to that of Japan in the emerging democracy-technology alliance against China led by the US.

Japan has continued its pro-US stance under President Biden’s administration. In their joint leader’s statement in spring of 2021, Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide and President Joe Biden affirmed their commitment to strengthening bilateral trade relations and more broadly US-Japan alliance. They also voiced their concerns over “Chinese activities that are inconsistent with the international rules-based order, including the use of economic and other forms of coercion” (The White House, 2021). Early this year, Japan reached an agreement with the US to scale back tariffs on Japanese steel that had been put in place due to the US imposition of Section 232 on steel. The 25 percent tariffs on steel will be transformed into a “so-called tariffrate quota, an arrangement in which higher levels of imports are met with higher duties” (Swanson, 2022). Under this arrangement, Japan will be able to export 1.25 million metric tons of steel for duty free each year, while any excess amount will be subject to the 25 percent tariff (Swanson, 2022). These are favorable signs for US-Japan trade relation, which is expected to remain strong during the Biden administration.

In Korea, the election of a new president in March 2022 heralds a potential shift in Korean trade politics. During his election campaign, the incoming President Yoon Suk-yeol has clearly indicated his intentions to strengthen Korea-US relations. He proclaimed that “Seoul should seek a comprehensive strategic alliance with Washington”, indicating the need to strengthen Korea-US cooperation on semiconductor, battery, cyber-tool, space, nuclear energy, pharmaceuticals and green technologies (Yoon, 2022). Under the new political leadership, Korea’s trade position of strategic ambiguity is likely to change. Noting that “Korea has succumbed to Chinese economic retaliation at the expense of its own security interests” in the case of THAAD deployment, incoming President Yoon stated “a new era of Seoul-Beijing cooperation should be based on the principle that differences (between the two) should not get in the way of economic issues.” (Yoon, 2022). While it is too early to make conclusive remarks on the trajectory of Korea’s trade positions, the trade priorities of the newly elected Korean president signal that Korea and Japan are more likely to find their paths crossing in the coming years.

Tables & Figures

Table 1.

Japan and Korea’s Export and Import with China, 2000-2019

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution.

References

-

Abe, S. 2015. “Toward an Alliance of Hope - Address to a Joint Meeting of the U.S. Congress by Prime Minster Shinzo Abe. Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. April 29.

https://japan.kantei.go.jp/97_abe/statement/201504/uscongress.html (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Baschuk, B. and J. Lee. 2021. “South Korea ‘Seriously’ Looking to Join CPTPP Following China Bid.” The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/10/08/asiapacific/politics-diplomacy-asia-pacific/south-korea-join-cptpp-china-bid/ (accessed March 22, 2022). -

Choi, B.-I. 2018a. “Saving KORUS from Trump.”

Global Asia , vol. 13, no. 2. -

Choi, B.-I. 2018b.

Northeast Asia in 2030: Forging Ahead or Drifting Away . Seoul: Asiatic Research Institute. -

Choi, B.-I. 2020. “Global Value Chain in East Asia Under “New Normal”: Ideology-Technology-Institution Nexus.”

East Asian Economic Review , vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 3-30.

-

Choi, B.-I. and J. S. Oh. 2021.

Politics of East Asian Free Trade Agreements: Unveiling the Asymmetry between Korea and Japan . Oxford and New York: Routledge. -

Davis, C. L. and S. Meunier. 2011. “Business as Usual? Economic Responses to Political Tensions.”

American Journal of Political Science , vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 628-646.

-

Deacon, C. 2021. “(Re)producing the ‘History Problem’: Memory, Identity and the Japan-South Korea Trade Dispute.”

The Pacific Review .https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2021.1897652 (accessed March 17, 2022) -

Diaz, A. and S. Zhang. 2017. “Angered by U.S. Anti-missile system, China Takes Economic Revenge.” CBS News, April 7, 2017.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/china-retaliatessouth-korea-us-thaad-missile-defense-lotte-and-k-pop/ (accessed February 21, 2022) -

Fefer, R. F. 2021. “Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act 1962.” CRS in Focus, November 4. Congressional Research Service.

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10667.pdf (accessed February 27, 2022) -

Ikenberry, G. J. 2004. “American Hegemony and East Asian Order.”

Australian Journal of International Affairs , vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 353-367.

-

Ikenberry, G. J. 2016. “Between the Eagle and the Dragon: America, China, and Middle State Strategies in East Asia.”

Political Science Quarterly , vol. 131, no. 1, pp. 9-43.

-

Korea International Trade Association. 2021. “Korea’s FTA Expects to Cover 77 Percent of Its Total Trade.” January 5.

https://www.kita.net/cmmrcInfo/cmmrcNews/cmercNews/cmercNewsDetail.do?searchReqType=detail&nIndex=1805782&no=8750&classification=130001 (accessed March 22, 2022) (in Korean) -

Koo, T.-G. 2021. “South Korea Applies to Join CPTPP after China’s Bid.” The Dong-A Ilbo, December 14.

https://www.donga.com/en/article/all/20211214/3082039/1 (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency. 2017. “US Perspective: The Past Five Years of KORUS FTA.” Global Market Report, no. 17-011.

https://dream.kotra.or.kr/kotranews/cms/indReport/actionIndReportDetail.do?SITE_NO=3&MENU_ID=280&CONTENTS_NO=1&pHotClipTyName=DEEP&pRptNo=7334 (accessed March 22, 2022) (in Korean) -

Kwan, C. H. 2019. “The China-US Trade War: Deep-Rooted Causes, Shifting Focus and Uncertain Prospects.”

Asian Economic Policy Review , vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-18. -

Lee, J. J. 2015. “The Truth about South Korea’s TPP Shift: A Look at the Reasons Behind Seoul’s Recent Rethinking.” The Diplomat, October 23.

https://thediplomat.com/2015/10/the-truth-about-south-koreas-tpp-shift/ (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Leonard, J. 2022. “One Year into His Term, Biden Finds Himself Boxed in on China.” Bloomberg Businessweek, January 19.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-19/china-fell-short-on-trade-deal-what-that-means-for-biden-dems-in-midterms (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Lim, D. J., Ferguson, V. A. and R. Bishop. 2020. “Chinese Outbound Tourism as an Instrument of Economic Statecraft.”

Journal of Contemporary China , vol. 29, pp. 916-933.

-

Lobosco, K. 2022. “Why Biden is Keeping Trump’s China Tariffs in Place.” CNN Politics, January 26.

https://edition.cnn.com/2022/01/26/politics/china-tariffs-biden-policy/index.html (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2022. Free Trade Agreement (FTA)/ Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) and Related Initiatives.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/fta/index.html (accessed February 21, 2022) -

Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. 2018. “KORUS FTA Outcomes and Explanations [Files].”

http://www.motie.go.kr/motie/ne/presse/press2/bbs/bbsView.do?bbs_cd_n=81&bbs_seq_n=160802 (accessed March 22, 2022) (in Korean) -

Obama, B. 2016. “Statement by the President on the Signing of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” The White House-President Barack Obama, February 3.

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/03/statementpresident-signing-trans-pacific-partnership (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Office of the US Trade Representative. 2017a. “Joint Statement by the United States, European Union and Japan at MC11.” December 12.

https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/pressoffice/press-releases/2017/december/joint-statement-united-states (accessed February 27, 2022) -

Office of the US Trade Representative. 2017b. “Opening Plenary Statement of USTR Robert Lighthizer at the WTO Ministerial Conference.” December 11.

https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/pressoffice/press-releases/2017/december/opening-plenary-statement-ustr (accessed February 27, 2022) -

Office of the US Trade Representative. 2021. “Fact Sheet: The Biden-Harris Administration’s New Approach to the U.S.-China Trade Relationship.” October 4.

https://ustr.gov/index.php/about-us/policyoffices/press-office/press-releases/2021/october/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administrationsnew-approach-us-china-trade-relationship (accessed March 18, 2021) -

Pempel, T. J. 2019. “Right Target; Wrong Tactics: the Trump Administration Upends East Asian Order.”

The Pacific Review , vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 996-1018.

-

Ravenhill, J. 2017. “Regional Trade Agreements.” In Ravenhill, J. (ed.)

Global Political Economy . Oxford: Oxford University Press. -

Shelton, J. 2021. “Look Skeptically at China’s CPTPP Application.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. November 18.

https://www.csis.org/analysis/look-skepticallychinas-cptpp-application (accessed March 22, 2022) -

Sohn, Y. 2019. “South Korea under the United States–China Rivalry: Dynamics of the Economic-Security Nexus in Trade Policymaking.”

The Pacific Review , vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1019-1040.

-

Swanson, A. 2022. “The U.S. and Japan Strike a Deal to Roll Back Trump-Era Steel Tariffs.” The New York Times, February 7.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/07/business/economy/us-japan-steel-tariffs.html (accessed March 18, 2022) -

Terada, T. 2019. “Japan and TPP/TPP-11: Opening Black Box of Domestic Political Alignment for Proactive Economic Diplomacy in Face of Trump Shock.”

The Pacific Review , vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1041-1069.

-

The White House. 2021. “U.S.-Japan Joint Leaders’ Statement: U.S.-Japan Global Partnership for a New Era.” April 16.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statementsreleases/2021/04/16/u-s-japan-joint-leaders-statement-u-s-japan-global-partnership-for-anew-era/ (accessed March 18, 2022) -

The White House-President Barack Obama. n.d. “The Trans-Pacific Partnership: What’s at Stake.”

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/economy/trade (accessed February 22, 2022) -

The World Bank. 2022. World Development Indicators [Data set].

https://databank.world bank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed February 24, 2022) -

Urata, S. 2020. “US–Japan Trade Frictions: The Past, the Present, and Implications for The US–China Trade War.”

Asian Economic Policy Review , vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 141-159.

-

U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. Trade in Goods with China [Data set].

https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html (accessed February 24, 2022) -

Williams, B. R., Cimino-Isaacs, C. D. and A. Regmi. 2019. “Stage One U.S.-Japan Trade Agreements.” CRS Report, no. R46140. Congressional Research Service.

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46140.pdf (accessed March 17, 2022) -

World Integrated Trade Solution. [Data set].

https://wits.worldbank.org/Default.aspx? lang=en (accessed February 24, 2022) -

Yoon, S.-Y. 2022. “South Korea Needs to Step Up.” Foreign Affairs, February 8.

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/south-korea/2022-02-08/south-korea-needs-step (accessed March 22, 2022)