- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 28, No. 4, 2024. pp. 391-419.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2024.28.4.440

Number of citation : 0Diplomatic Engagement and Economic Influence: The Interplay of Chinese OFDI and High-Level Visits

|

Kyung Hee University |

|

|

Kwangwoon University |

Abstract

This study investigates the interdependence between Chinese outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) and high-level visits. Using a simultaneous equation model (SEM) and Three-Stage Least Squares (3SLS), we analyze a panel dataset comprising 146 host countries over the period 2003 to 2021, covering the tenures of Presidents Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. We further explore how the relationship between OFDI and diplomatic visits differs across developing and developed countries, as well as how shifts in political leadership influence these dynamics. Our empirical findings reveal a robust interdependence between China’s economic actions and diplomatic engagements. Specifically, there is a strong mutual influence between OFDI and visits to developing countries. In contrast, while visits positively impact OFDI in developed countries, there is no reciprocal influence. Moreover, the interdependence between OFDI and visits was particularly evident during President Xi’s tenure, whereas no such relationship was established during President Hu’s tenure. Our findings emphasize the importance of high-level visits in driving OFDI and highlight the critical role of economic engagement in achieving diplomatic goals. Furthermore, by examining this relationship across two presidential tenures, we offer a nuanced perspective on how host country characteristics and leadership transitions shape the dynamics between OFDI and diplomatic visits.

JEL Classification: F21, F23, F59

Keywords

Outward Foreign Direct Investment, Economic Diplomacy, High-Level Visits, Foreign Policy, Simultaneous Equation Model

I. Introduction

China has emerged as the world’s second-largest economy, and its economy and diplomacy have become increasingly intertwined. China officially mentioned economic diplomacy (in Chinese, “JingJi WaiJiao/经济外交”) for the first time during President Hu Jintao’s (hereafter “President Hu”) tenure (Medeiros, 2009). Chinese economic diplomacy aims to achieve its economic goals through diplomatic activities and, conversely, achieve its diplomatic goals through economic activities (Heath, 2016). This strategy includes expanding trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) via international collaborations and diplomatic efforts, as well as expanding its influence in international matters through economic and technological support (“经济外交.” Baidu Baike. Accessed February 24, 2024).

Existing literature on economic diplomacy has explored various dimensions of how diplomacy impacts international business and relations. These studies have mainly focused on understanding the significant role of diplomatic factors in commercial activities, such as trade and FDI. This includes studies on how state and official visits (hereafter “visits”) affect trade (Beaulieu et al., 2020; Nitsch, 2007), the role of foreign services (embassies and consulates) in promoting trade (Rose, 2007; Yakop and van Bergeijk, 2011), the impact of visits on FDI (Adam and Tsarsitalidou, 2023; Kodila-Tedika and Khalifa, 2023; Zhang and Daly, 2011), and the influence of promotion agencies on FDI attraction (Cass, 2007; Harding and Javorcik, 2012; Morisset, 2003). However, research has also analyzed the economic drivers of high-level visits (Fuchs, 2018; Lebovic and Saunders, 2016; Wang and Stone, 2023). Thus, the current body of research focuses on the unidirectional relationship between economics and diplomacy.

However, much of this research has treated the relationship between economics and diplomacy as unidirectional, examining how diplomatic activities influence economic outcomes while largely overlooking how economic actions, such as outward foreign direct investment (OFDI), may reciprocally influence diplomatic behaviors. Moons and van Bergeijk (2017) indicated that there may be a simultaneous and endogenous relationship between visits and commercial activities, suggesting that the interactions between these two variables may be more complex and interdependent than previously thought. This raises the question of whether an interdependent relationship exists between Chinese high-level visits and OFDI.

This study aims to address this gap by investigating the interdependence between Chinese OFDI and high-level visits. Using a simultaneous equation model (SEM) and Three-Stage Least Squares (3SLS) to address endogeneity concerns, we analyze a panel dataset comprising 146 host countries over the period 2003 to 2021, spanning the tenures of Presidents Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping (hereafter “President Xi”). We further explore how the relationship between OFDI and diplomatic visits differs across developing and developed countries, as well as how shifts in political leadership influence these dynamics.

Our empirical findings reveal a robust interdependence between China’s economic actions and diplomatic engagements. Specifically, there is a strong mutual influence between OFDI and visits to developing countries. In contrast, while visits positively impact OFDI in developed countries, there is no reciprocal influence. Moreover, the interdependence between OFDI and visits was particularly evident during President Xi’s tenure, whereas no such relationship was established during President Hu’s tenure. This suggests that China’s economic diplomacy is not only reflects its foreign policy but is also closely tied to its leadership’s strategic vision.

This study contributes to the literature on international business and relations by providing empirical evidence of the reciprocal relationship between Chinese OFDI and high-level visits. Our findings emphasize the importance of high-level visits in driving OFDI and highlight the critical role of economic engagement in achieving diplomatic goals. Furthermore, by examining this relationship across two presidential tenures, we offer a nuanced perspective on how host country characteristics and leadership transitions shape the dynamics between OFDI and high-level visits.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and outlines our hypotheses. Section 3 presents the econometric model and data. Section 4 discusses the empirical findings, and Section 5 concludes the study.

II. Literature Review

Since the early 2000s, China’s “Go Global” strategy and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched in the mid-2010s, have significantly boosted its OFDI, making it the world’s second-largest global investor. International business scholars have extensively explored the determinants of Chinese OFDI. Drawing on Dunning’s (2000) eclectic theory of FDI, these studies typically consider the unique aspects of China’s capital markets, including the pursuit of new markets, natural resources, strategic assets, and efficiency improvements. Significant motivators for Chinese OFDI include market size, access to energy, and acquisition of strategic assets such as technology and brands (Chang, 2014; Deng, 2004; Zhang and Daly, 2011). Additional influences include cultural proximity, labor costs, and business environment (Buckley et al., 2007; Chen and Lin, 2018). Political and institutional factors are also crucial, particularly in countries with less governance or political instability, as they affect the direction of OFDI (Buckley et al., 2007; Kolstad and Wiig, 2012; Ramasamy et al., 2012). The role of state support for state-owned enterprises in directing OFDI is well-recognized (Deng, 2004; Stone et al., 2022).

Recent research has begun to emphasize the complexity of international relations, suggesting that the traditional determinants of FDI may not fully capture the dynamics that influence investment decisions. The impact of visits on economic activities has been extensively studied, indicating that such engagements can lead to significant policy effects and economic agreements (Moons and van Bergeijk, 2017; Nitsch, 2007; Rose, 2007). Lin et al. (2017) demonstrated that state visits have had a positive effect on trade between China and Africa. Beaulieu et al. (2020) found that state visits were a form of presidential marketing that promoted trade. The importance of these visits to promote trade, official aid, and FDI underscores the role of diplomacy in economic strategies.

Additionally, the role of visits has been increasingly recognized as pivotal in shaping FDI destinations (Adam and Tsarsitalidou, 2023; Kodila-Tedika and Khalifa, 2023; Zhang et al., 2014). Sun and Liu (2019) described a higher diplomatic partnership with China as a benefit of OFDI. Desbordes (2010) indicated that better diplomatic relations with other countries translated into higher FDI, whereas the opposite was true if the host country experienced an intra-border conflict. Zhang et al. (2014) found that Chinese diplomatic activities promoted OFDI. These studies suggest that diplomatic engagement is critical for foreign investors.

Another stream of literature investigates the determinants of diplomatic visits, focusing on military (such as arms exports and military spending), economic (including Gross Domestic Product [GDP], population, trade, and energy openness), institutional and political (e.g., United Nations General Assembly [UNGA] voting behavior, levels of democracy, United Nations [UN] sanctions, and Permanent Membership in the UN Security Council) drivers (Fuchs, 2018; Lebovic and Saunders, 2016). Particularly noteworthy is the relationship between economic factors and diplomacy, which is central to this study. Economic ties have been shown to significantly increase the likelihood of diplomatic visits by high-ranking officials, such as Presidents or Cabinet members (Lebovic and Saunders, 2016). Positive economic exchanges with China have similarly been linked to an increase in visits by Chinese leaders (Fuchs, 2018). This body of the literature suggests that substantial FDI flows are more likely to precipitate high-level visits.

Furthermore, many studies suggest simultaneity and endogeneity between economic activities and visits (Beaulieu et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2017; Moons and van Bergeijk, 2017). Several studies have empirically tested the causal relationship between FDI and political conflicts. For instance, Desbordes and Vicard (2005) found that political interactions and armed conflict could affect the location choices of multinational companies. Polachek et al. (2007) discovered that FDI and international conflicts were interactive. Although studies have made significant strides in examining the impact of diplomatic factors on economics and the determinants of diplomatic activities, evidence regarding the interdependence between high-level visits and FDI is lacking. In this regard, this study develops the following hypotheses to address the research issues raised earlier.

Economic diplomacy, a strategic tool employed by governments and non-state actors, plays a pivotal role in influencing decisions regarding cross-border economic activities (Bayne and Woolcock, 2003; Okano-Heijmans, 2011). For example, in the United States, a country leader’s visit can increase FDI by up to one percentage point per year (Adam and Tsarsitalidou, 2023). Moons and van Bergeijk (2017) argued that economic diplomacy fosters mutual trust and lowers transaction costs by providing information that is often inaccessible to private parties because of information asymmetry or the nature of public goods. Its widespread use by governments to impact FDI is a testament to its effectiveness in enhancing a country’s brand and image (Rana, 2007).

Similar to leaders everywhere, those in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) considered economics when practicing diplomacy. Many scholars acknowledge that, for example, the desire to gain access to Soviet technologies and trade expansion informed Chinese diplomacy in the 1950s and the 1960s (Heath, 2016). Gueldry and Liang (2016) mentioned that there were several presidential visits to Africa before Chinese FDI rapidly increased. President Hu signed numerous bilateral agreements while visiting various countries in Africa and Latin America. They also pointed out that, during his tenure, the strategic use of “energy diplomacy” ensured a steady energy supply and sustained economic growth. These visits were often accompanied by business delegations from Chinese companies interested in business opportunities in the host country (Fuchs, 2018). High-level visits offer a critical platform for direct negotiations with senior government officials on investment protection and other regulations, potentially resulting in favorable investor conditions. Potential investors can also directly raise concerns or difficulties related to domestic investment and request senior government officials to resolve them. Successfully addressing investment hurdles can increase domestic FDI growth.

Meanwhile, as Park and Jung (2020) argued, high levels of investment could increase economic stakes in the host country, prompting more frequent and strategically important diplomatic visits to ensure the stability and profitability of these investments. This dynamic is exemplified by President Xi’s promotion of the BRI initiative, particularly through multiple visits to Kazakhstan. For example, during his first visit in September 2013, President Xi launched the BRI. Subsequently, in May 2015, he revisited President Nursultan Nazarbayev for discussions, emphasizing major ongoing projects in infrastructure, energy, finance, and security cooperation. These meetings spurred significant early success in developing the Silk Road Economic Belt, a venture greatly valued by China. President Xi’s subsequent visits in 2017 and 2022 further solidified cooperation and led to additional agreements under the BRI (MoFA and PRC). This cooperation was followed by investment in infrastructure construction. Thus, the significant inflow of FDI into a host country may require multiple diplomatic visits to protect and enhance existing economic relationships. Thus, we hypothesize that high-level visits and investments from China can simultaneously attract each other. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

III. Empirical Model and Data

1. Model Specification

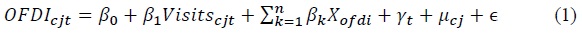

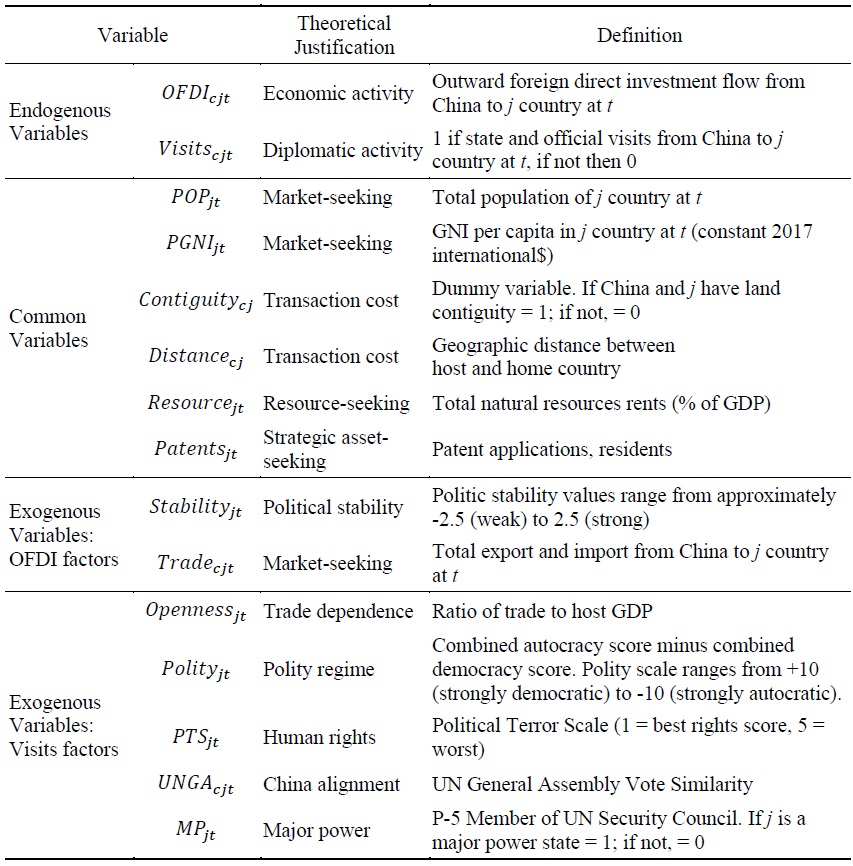

This study hypothesizes that Chinese high-level visits promote OFDI, and OFDI attracts high-level visits. We capture these two effects in the following SEMs for OFDI and visits.

where

The determinants of Chinese OFDI in Equation (1) are based on the theoretical framework of Dunning (2000) and the empirical literature of Zhang et al. (2014). These sources identified the motivations behind Chinese OFDI as including market-seeking, resource-seeking, strategic asset-seeking, efficiency-seeking, as well as political (Park and Jung, 2020) and diplomatic objectives. It has been established that market size, physical proximity, and product diversion to export markets significantly influence foreign investors’ investment decisions (Chang, 2014). Therefore, our analysis considers population (POP), per capita gross national income (PGNI), trade volume (Trade), geographical distance (Distance), and border adjacency (Contiguity). Factors such as energy acquisition, knowledge, and political factors also affect investment decisions (Deng, 2007; Zhang and Daly, 2011). Consequently, we include the host country’s natural resources (Resources), patent registrations (Patents), and political stability (Stability) as variables in our empirical analysis. Additionally, fostering strong diplomatic relationships is recognized as a catalyst for investment. Hence, we include variables representing high-level visits to China (Visits). The visits include the Chinese President’s State Visits as well as both the premier’s official and working visits. We did not include multilateral meetings and summits such as President Xi’s visit to Brazil for the 11th BRICS Summit 2019 (MoFA, PRC).

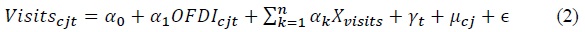

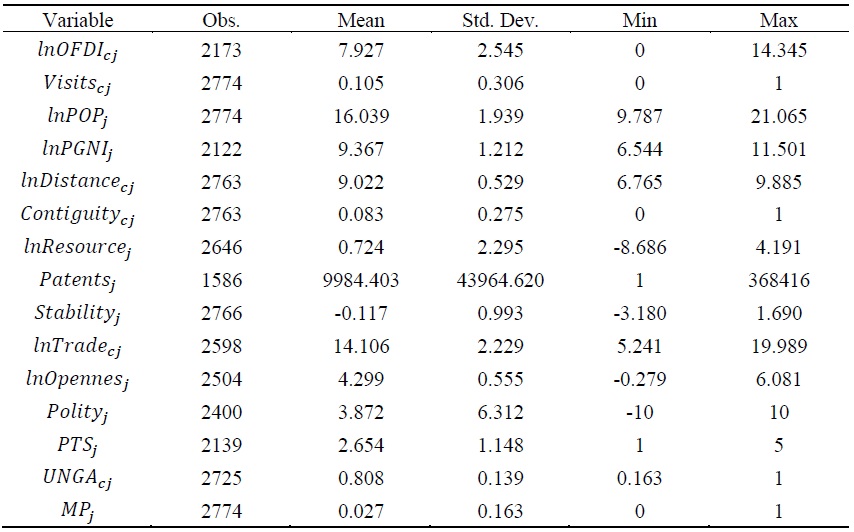

For the Visits equation (2), we follow Fuchs (2018). The equation considers several geo-economics factors, including POP, PGNI, Distance, Contiguity, Resource, and Patents variables. These factors are also common variables that determine Equation (1). We further control for bilateral trade intensity (Openness), as it encourages officials to take action to facilitate trade efforts. The institutional variables include the level of democracy (Polity) in the country. This is captured by the Polity5 indicator variable of the combined autocracy score minus the combined democracy score. We also incorporate variables associated with worldwide concerns such as human rights (PTS). We measure the political importance of both the UNGA’s (UNGA) voting alignment with China and the binary variables that take the value of one if a country is a major power (MP) under Permanent Membership in the UN Security Council. Table 1 provides a detailed explanation of each variable’s theoretical justification and definition.

SEMs are estimated using either Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) or the more efficient three-stage estimation methods. In this study, we use the latter method because it allows for correlations between unobserved errors in different equations and also enables an analysis of the interdependence among endogenous variables related to common exogenous variables. The 3SLS method provides unbiased and consistent estimators of the coefficient parameters of exogenous variables by exploiting the information held by the variance-covariance matrix of the residual terms (Wooldridge, 2010). According to Cornwell et al. (1992), the SEM estimate can solve simultaneity and endogeneity biases, making the 3SLS estimation the most appropriate approach for our econometric methods.

Therefore, we employ a simultaneous equation model (SEM) and Three-Stage Least Squares (3SLS) to address potential simultaneity and endogeneity between Chinese OFDI and high-level diplomatic visits. SEM allows us to capture the interdependent relationship between these two variables, while 3SLS provides efficient estimates by accounting for correlations between unobserved errors across equations. This approach ensures that our results reflect the underlying causal dynamics more accurately, mitigating biases that could arise from simultaneity. The SEMs estimations are performed using the statistical software package STATA/17.

2. Data Source and Statistics

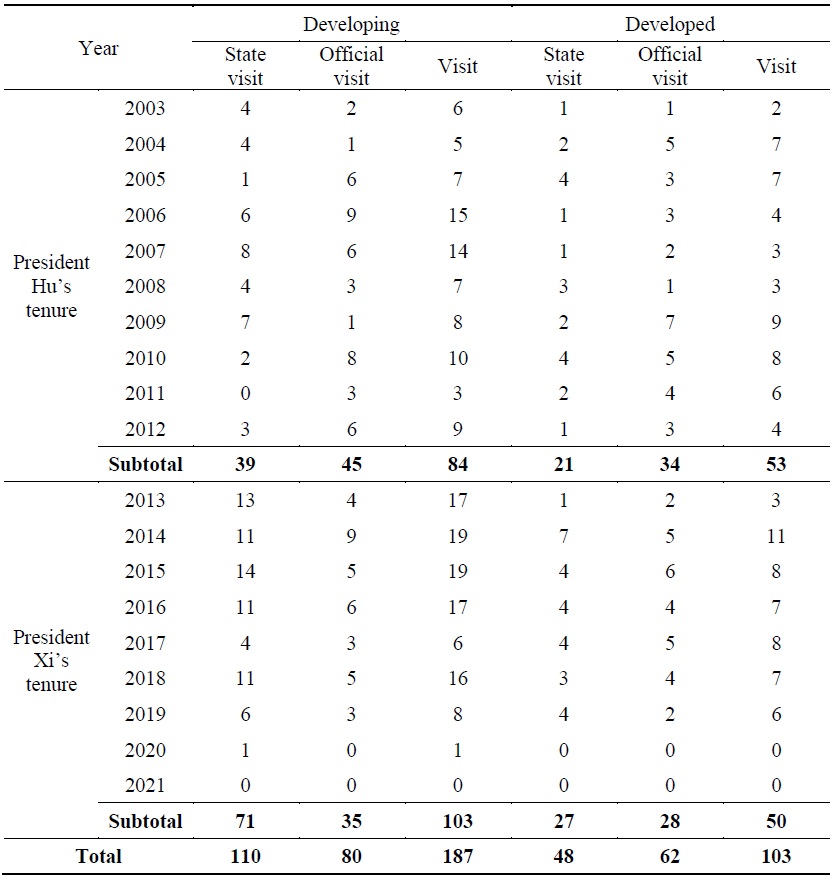

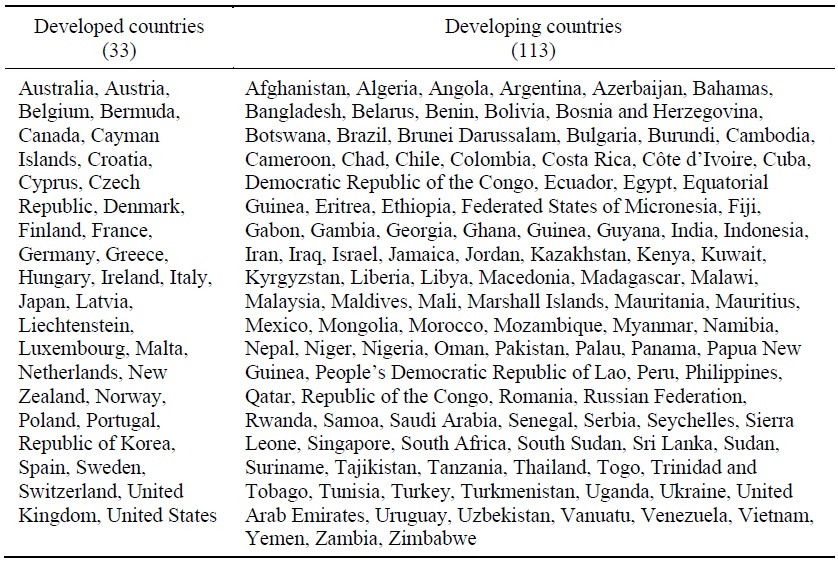

The dataset consists of 2,744 observations, over the period 2003–2021. We analyze a sample of 146 host countries, comprising 33 developed and 113 developing countries (see Appendix B2). Table 2 provides the summary statistics of the key variables. When analyzing data, variables with large gaps in their minimum and maximum values can negatively affect normality if they are excessively skewed or contain outliers. These variables are converted into natural logarithm (

The

Data for

IV. Empirical Results

1. Baseline Results

We conduct a regression analysis of each equation using the panel datasets. It is important to consider the characteristics of different data types to derive optimal results through a panel data analysis. As an example, should we use a fixed or random effects model because the dependent variable in Equation (1) is continuous? The Hausman test (not shown) strongly suggests using random effects rather than fixed effects for the data. Moreover, Wooldridge’s autocorrelation and log-likelihood tests indicate that our model has heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. Therefore, we employ a generalized least-squares estimator to address these concerns. As the dependent variable is binary, we use a panel logit model for Equation (2). We also include a year dummy variable to control for the time effect.

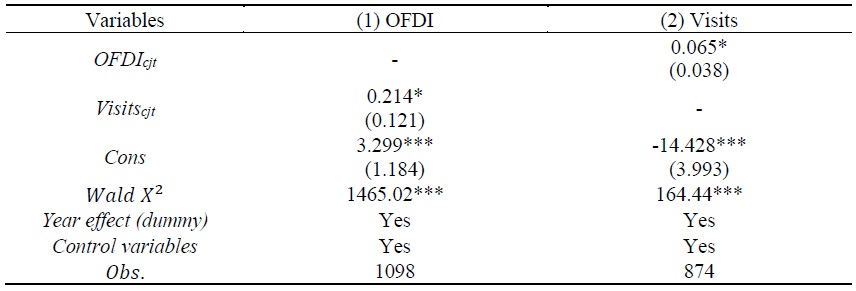

Table 3 presents the regression results for each equation. The impact of visits on OFDI is positive and significant at the 10% level. Similarly, the influence of OFDI on visits is positive and significant at the 10% level. These findings suggest a potential interdependent relationship between Chinese OFDI and number of visits. The following section presents the results of analyzing this relationship using the 3SLS estimator.

2. Main Results

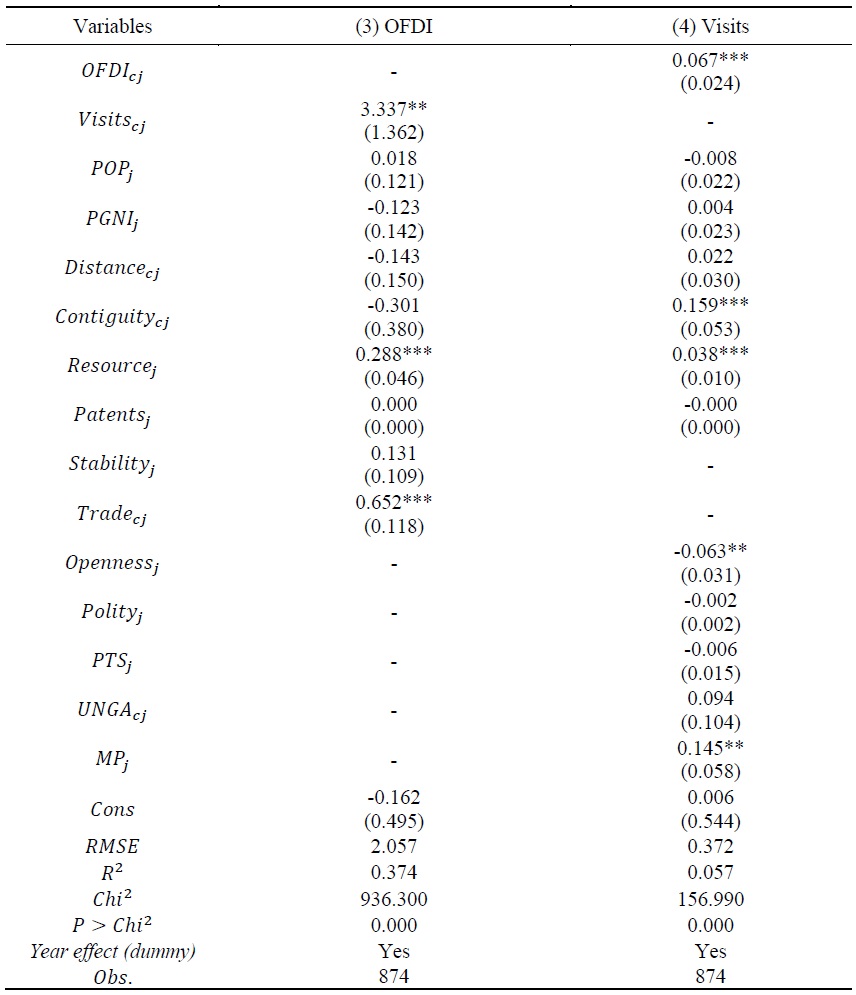

This section presents several findings from simultaneous equation estimates. Columns (3) and (4) in Table 4 illustrate the results of Equations (1) and (2), respectively. When the analysis includes the entire sample, the results reveal that OFDI, and high-level visits mutually impact each other. This demonstrates that high-level visits effectively strengthen economic ties and promote OFDI, whereas OFDI encourages diplomatic engagement. This provides strong evidence supporting our

The estimation results for the OFDI equation in Column (3) are as expected. The results for abundant resources, GNI, and population are consistent with those of Chang (2014) and Kolstad and Wiig (2012). The presence of abundant resources in a host country significantly affects OFDI, highlighting China’s strategic interest in securing important raw materials and energy resources. Moreover, trade positively impacts OFDI at the 1% significance level. However, geographical distance, contiguity, and patent registration are not statistically significant, which is consistent with the results of Buckley et al. (2007).

The coefficients of contiguity and resources in the visit equation are positive at the 1% significance level. Major power positively impacts visits, whereas openness has a negative effect at the 5% significance level. In other words, countries with more open economies face fewer trade barriers and receive fewer visits to China. Interestingly, this result contradicts the findings of Fuchs (2018). This suggests that China targets diplomatic visits at countries where negotiations and agreements can more significantly impact market access and trade conditions.

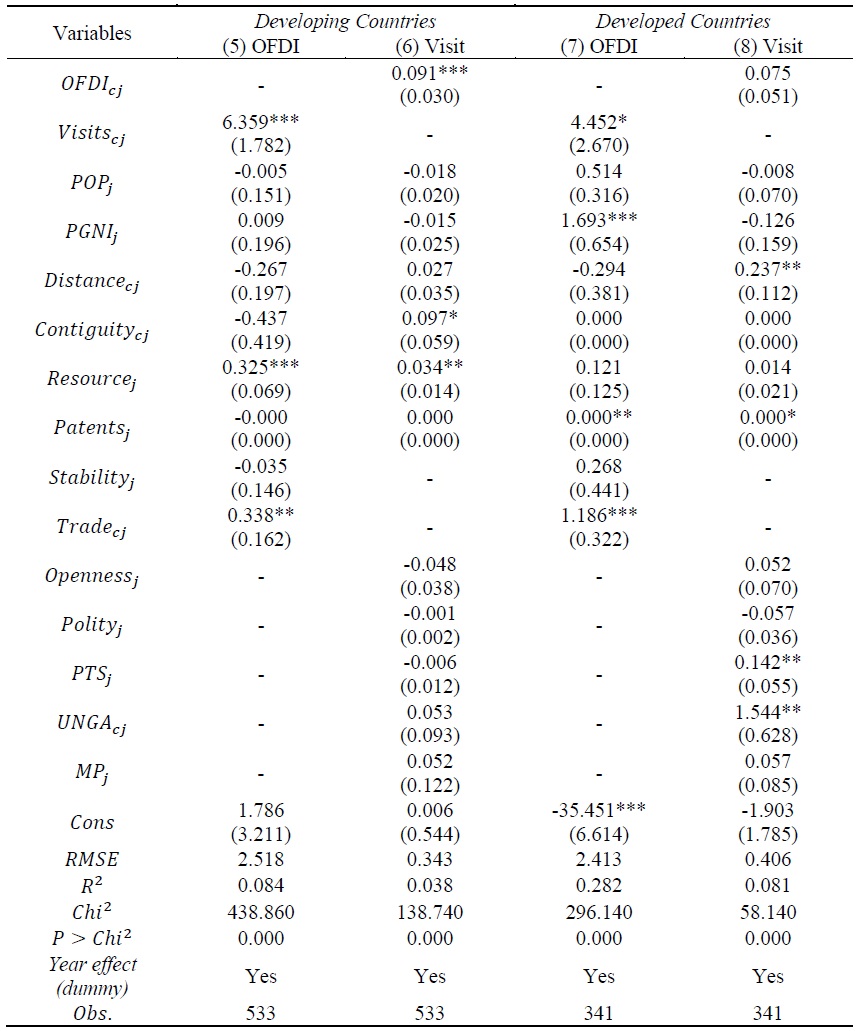

We further analyze the impact across different country classifications to understand how visits and OFDI interact in diverse economic contexts. The classification of countries follows the International Monetary Fund (see Table B2). In Table 5, Columns (5) and (6) report the results for developing countries, and Columns (7) and (8) indicate the results for developed countries. In developing countries, there is a robust mutual influence between visits and OFDI, with both positively impacting each other at the 1% significance level. This suggests a strong reciprocal relationship wherein diplomatic engagements facilitate investments, and vice versa. This could be owing to several factors including the pursuit of natural resources, new markets, or strategic geopolitical positioning. Specifically, the presence of natural resources seems to be a significant attractor of both investments and visits, indicating that China’s engagement in these regions may be heavily driven by resource acquisition needs.

In developed countries, visits positively affect OFDI at the 10% significance level, indicating that diplomatic efforts are important for fostering economic ties. However, OFDI has no reciprocal influence on visits. This suggests that China’s diplomatic missions in these countries are perhaps more about strengthening existing economic ties and less about soliciting new investments. This conclusion is supported by studies indicating that China’s OFDI in developed countries often focuses on specific types of investments, such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A), which do not rely heavily on diplomatic visits but rather on strategic goals such as acquiring advanced technology, brands, and resources (Chen et al., 2022; Deng, 2004). The significant positive effects of the PGNI and patents on investment highlight that economic strength and intellectual property capabilities in developed countries are key attractors of Chinese investment.

For developed countries, the positive impacts of patents, human rights issues, and UN voting alignment with China suggests that diplomatic engagements are influenced not only by economic but also by political and legal environments. This result aligns with the findings of Li and Choi (2022). These factors can represent an alignment in international policies, respect for intellectual property, broader political stability, and human rights conditions, which are all critical for long-term economic partnerships.

The variance observed between developing and developed countries underscores China’s strategic flexibility on the international stage. In developing countries, the focus on resources ensures that it secures the essential raw materials necessary for domestic growth. In contrast, in developed countries, China appears to leverage high-level visits to bolster technological collaborations and strengthen economic alliances, reflecting a nuanced approach based on the host country’s economic landscape and institutional maturity.

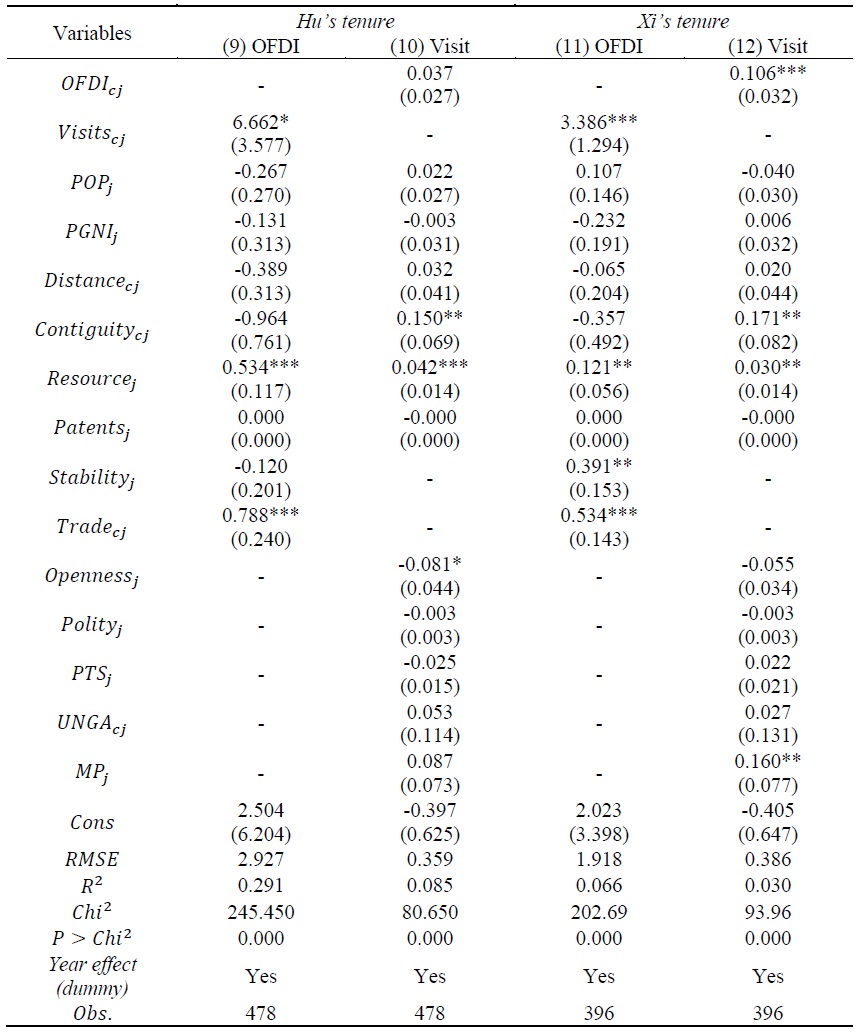

We also examine how leadership changes affect economic diplomacy. This is done by comparing the interrelationship between high-level visits and OFDI under the administrations of Presidents Hu and Xi. In Table 6, Columns (9) and (10) present the results of President Hu’s tenure, while Columns (11) and (12) report the results of President Xi’s tenure. During President Xi’s tenure, there is a strong, statistically significant mutual dependence between high-level visits and OFDI at the 1% level. This indicates a robust synergy in which diplomatic efforts and investments reinforce each other. This suggests a more aggressive or perhaps more coordinated approach to leverage high-level visits to bolster economic ties, and vice versa. This can reflect China’s aggressive foreign policy strategies, such as the BRI, in which visits are used to secure and enhance investment opportunities.

In contrast, during President Hu’s tenure, high-level visits positively impact OFDI, but only at the 10% significance level. Furthermore, the influence does not reciprocate from OFDI back to high-level visits. This suggests that, while high-level visits still enhance investment opportunities under Hu, the investments themselves do not necessarily lead to increased visits.

Natural resources and trade have consistently and positively influenced OFDI across both leadership tenure. This highlights China’s continued focus on securing resource supplies and enhancing trade relations through diplomatic channels. The presence of political stability becomes a significant factor only during Xi’s tenure. This may indicate a heightened focus on ensuring stable investment climates as part of a broader strategy for securing and deepening economic engagement.

In the visiting equation, natural resources and contiguity positively influence high-level visits in both administrations. This highlights the strategic importance of geographical and resource-based considerations in China’s diplomatic engagements. Trade openness negatively affects diplomatic visits during Hu’s tenure, suggesting that more open trade relations may have reduced the need for diplomatic intervention to secure economic agreements. This result contrasts with the findings of Fuchs (2018), suggesting a strategic shift wherein visits decline as trade barriers are reduced and economic relationships are already well established. Moreover, during President Xi’s tenure, being a major power positively affects the frequency of visits. This suggests a strategic emphasis on engaging with other major global players to reinforce China’s status and influence on the international stage. This result is consistent with the whole-sample model.

3. Robustness Check

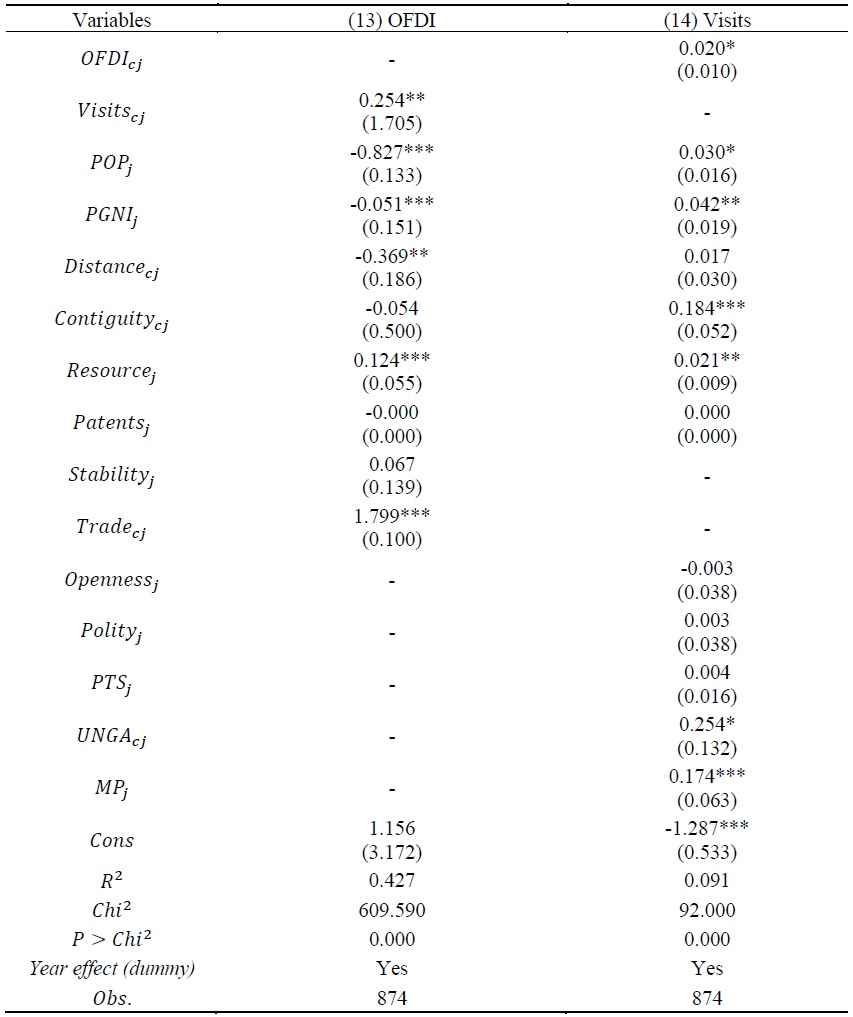

We use 2SLS as an alternative estimation method to assess the robustness of our model. Although simpler, comparing the results from 3SLS with those from 2SLS helps verify the consistency of our estimates. This method has been employed to estimate SEMs, such as in the work of Alesina and Perotti (1996). Columns (13) and (14) in Table 7 show the results for Equations (1) and (2), respectively. The results demonstrate that the relationship between OFDI and visits is positive, interdependent, and statistically significant. These findings support our empirical results.

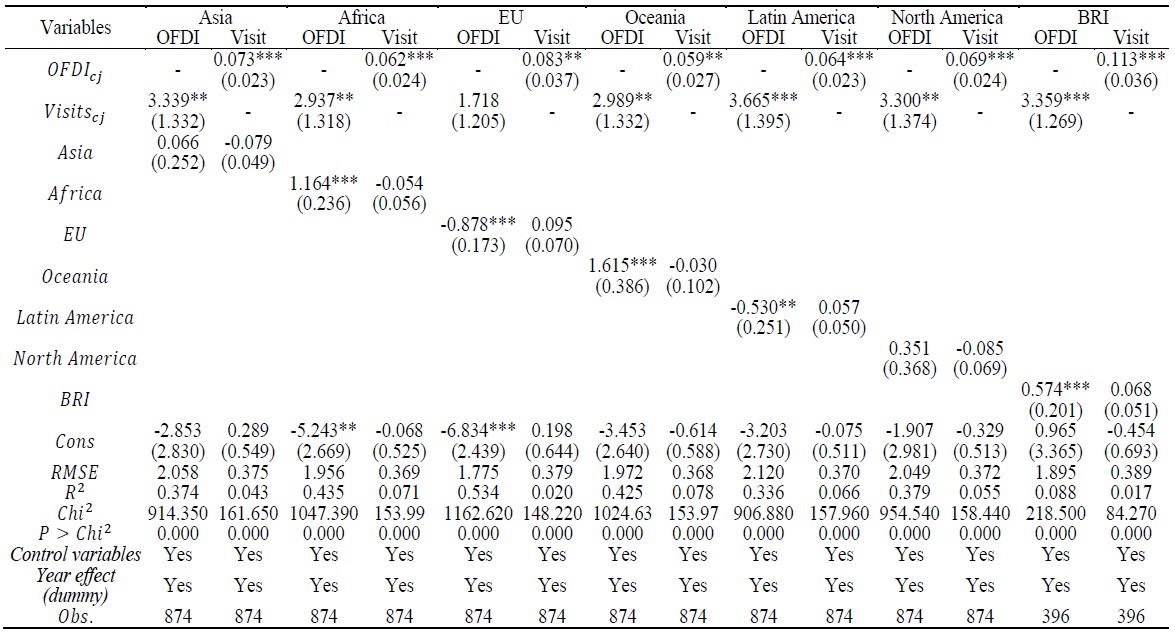

We add regional dummy variables to check the sensitivity of our results to different model specifications. Similar approaches have been employed in studies to assess model robustness and identify potential omitted variable biases, as Bleaney and Nishiyama (2002) note. The results of adding dummies for Asia, Africa, the European Union (EU), Oceania, Latin America, North America, and BRI countries are shown in Table 8. The BRI dummy spans from 2013 to 2021, whereas the dummies for the other regions cover 2003 to 2021. Our results consistently indicate a robust interdependent relationship between OFDI and visits across all analyses except for those that add the EU dummy.

In the OFDI equation, dummies for the African, Oceania, and BRI regions positively impact Chinese OFDI. This is because these are regions where Chinese investments are driven by strategic needs such as resources, infrastructure development, and enhancing connectivity under the BRI framework. Conversely, the dummies for the EU and Latin America negatively influence Chinese OFDI. This can be because of challenging regulatory environments, competitive markets, or political climates that are less conducive to Chinese investments. Although the effects in Asia and North America are positive, they are not statistically significant. This suggests that factors beyond regional characteristics play crucial roles in influencing OFDI in these areas. Additionally, the insignificance of the region dummies in the visit equation suggests that regional factors do not independently predict the likelihood of high-level visits, which are likely influenced by broader national strategies or other overarching considerations. Factors such as natural resources, contiguity, and major power status positively impact visits across all regions. This highlights China’s focus on resource-rich neighbors and globally influential countries. This, in turn, aligns with the strategic geopolitical and economic interests.

V. Conclusion

This study analyzes the interdependent relationship between Chinese OFDI and high-level visits by employing SEMs and a 3SLS estimation. Our investigation spans the period 2003 to 2021, covering the administrations of Presidents Hu and Xi, and analyzing data from 146 host countries. We further explore how OFDI and high-level visits may influence each other based on the country classifications and evolving leadership context.

The empirical results confirm the interdependence between Chinese economic relationships and diplomatic engagements. Specifically, high-level visits significantly promote OFDI, underscoring the importance of these diplomatic interactions in expanding China’s economic influence. Conversely, increased OFDI encourages further high-level visits, suggesting that economic investment serves as a precursor to more frequent diplomatic engagements. This reciprocal relationship highlights the strategic use of economic diplomacy by China to expand its economic interests as well as stabilize and strengthen its diplomatic ties with the host country. This aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. (2014) and Fuchs (2018).

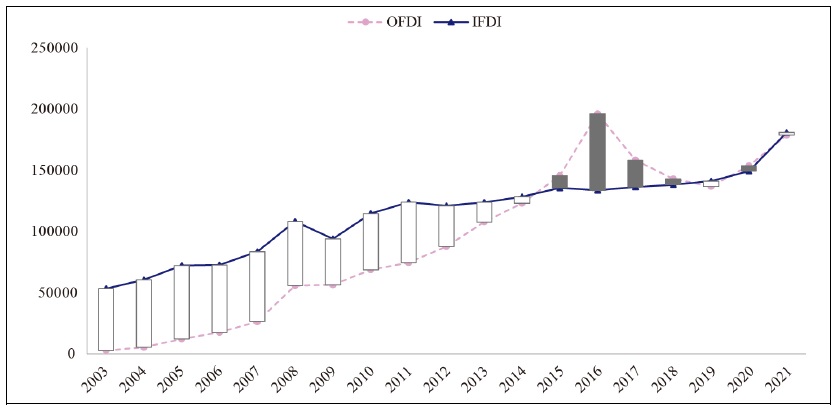

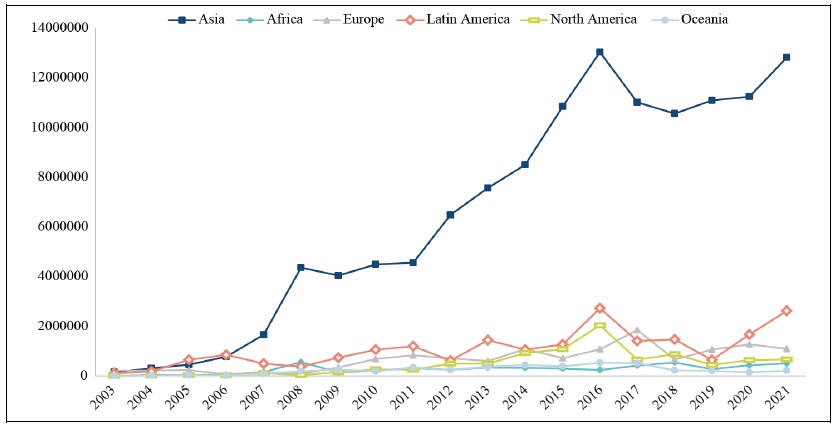

Interestingly, a strong mutual influence between OFDI and visits to developing countries, likely driven by China’s pursuit of natural resources and new markets. In contrast, while visits positively impact OFDI in developed countries, there is no reciprocal influence, indicating that diplomatic efforts may focus more on strengthening existing ties rather than expanding new economic engagements. Our study also finds that under President Xi’s leadership, the mutual dependency between OFDI and high-level visits was significantly stronger than that during President Hu’s tenure. This temporal variation reflects China’s increased emphasis on OFDI and high-level visits to developing countries during Xi’s presidency, particularly in Asia and Latin America (see Appendix A2). These areas experienced a notable rise in high-level visits and outbound investments, aligning closely with the BRI, which prioritizes infrastructure and resource-related projects. Meanwhile, visits to developed countries remained relatively stable, and the decline in OFDI to regions such as the US can be attributed to geopolitical tensions and stricter foreign investment, which posed challenges for Chinese corporations.

The shift in focus between these two leadership periods illustrates the strategic flexibility of China’s global economic diplomacy. Under President Hu, diplomatic efforts concentrated on securing energy resources, particularly in African and Latin American regions. In contrast, President Xi’s tenure adopted a broader approach, utilizing economic and diplomatic initiatives to advance China’s long-term objectives, including the “Great Rejuvenation.” These findings support the notion that Chinese economic diplomacy seeks to secure the resources, markets, capital, technologies, and skilled labor necessary for sustaining national development (Zhen, 2010). This suggests that China’s economic diplomacy is not merely a reflection of its foreign policy but also closely tied to its leadership’s strategic vision.

Understanding the interconnection between economic and diplomatic strategies has significant implications. For Chinese policymakers, these findings suggest that diplomatic strategies must be finely tuned to regional and economic contexts to effectively support the China’s global economic agenda. For international business leaders and investors, the results indicate that Chinese OFDI is likely to follow strategic diplomatic engagements, providing a predictive tool for assessing potential economic opportunities based on Chinese diplomatic activities. For developing countries, the interaction between China’s OFDI and high-level visits offers a valuable opportunity to align policies with China’s economic priorities to attract investments. Understanding China’s focus on resource-seeking and market expansion can help these countries formulate strategies to position themselves more favorably for Chinese investment. Academically, this study contributes to the broader discourse on economic diplomacy by providing empirical evidence on the interdependence between OFDI and high-level visits. It enhances our understanding of the strategic dimensions of Chinese international relations and business and offers a framework for other nations to analyze the potential impacts of their own economic diplomacy strategies.

However, this study has some limitations. The data used in this study are specific to China; therefore, the generalization of these results should be approached with caution. Specifically, it would not be reasonable to generalize our findings to other countries, as China’s economic system is uniquely characterized by a socialist market economy. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to research on economic diplomacy and suggests the need for further exploration of different dyads in future studies.

Tables & Figures

Table 1.

Variables’ Theoretical Justification and Definitions

Table 2.

Summary Statistics

Table 3.

Empirical Result of Equations (1) and (2)

Notes: 1) The regressions utilize the GLS estimator for Equation (1) and the Panel Logit estimator for Equation (2). 2) Standard errors are in parentheses. 3) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 4) “−” indicates excluded variables. 5) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 6) The analysis covers the full study period from 2003 to 2021.

Table 4.

OFDI and Visits Equations, Whole Sample

Notes: 1) Standard errors are in parentheses. 2) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 3) “−” indicates variables that are excluded. 4) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 5) The analysis covers the full study period from 2003 to 2021.

Table 5.

OFDI and Visits Equations, Country Classification

Notes: 1) Standard errors are in parentheses. 2) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 3) “−” indicates variables that are excluded. 4) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 5) The analysis is divided into 33 developing and 113 developed countries.

Table 6.

OFDI and Visits Equations, Changing in Nation’s Leadership

Notes: 1) Standard errors are in parentheses. 2) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 3) “−” indicates variables that are excluded. 4) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 5) The analysis spans the 2003-2012 presidency of Hu and the 2013-2021 presidency of Xi.

Table 7.

OFDI and Visits Equations, Robust Estimation

Notes: 1) Standard errors are in parentheses. 2) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 3) “−” indicates variables that are excluded. 4) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 5) The analysis covers the full study period from 2003 to 2021.

Table 8.

OFDI and Visits Equations, Adding Regional Dummy

Notes: 1) Standard errors are in parentheses. 2) * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. 3) “−” indicates variables that are excluded. 4) Year dummy variables are included but not reported in the table. 5) The analysis covers the full study period from 2003 to 2021.

Figure A1.

Chinese OFDI and IFDI (2003-2021)

Note: 1) 2003-2012: Presidency of Hu Jintao, 2013-2021: Presidency of Xi Jinping; 2) The white bars represent years when IFDI exceeded OFDI, while the black bars represent years when OFDI was greater than IFDI.

Source: Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

Figure A2.

Chinese OFDI by Region (2003-2021)

Source: Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

Table B1.

High-Level Diplomatic Visits

Note: 2003-2012: Presidency of Hu Jintao, 2013-2021: Presidency of Xi Jinping

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

Table B2.

Country Coverage

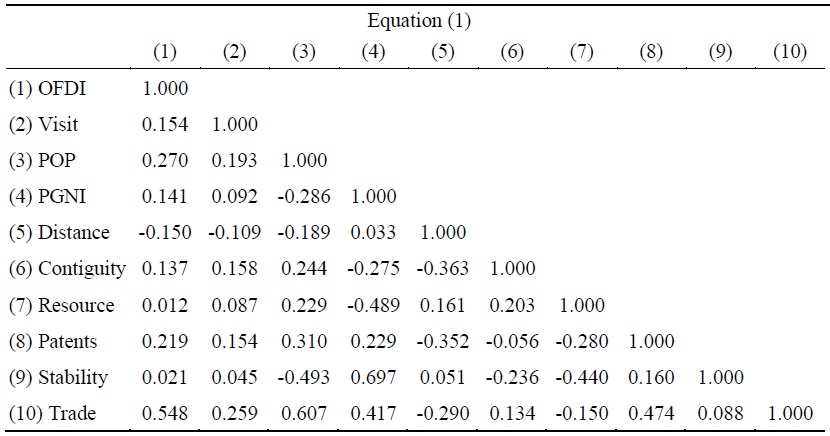

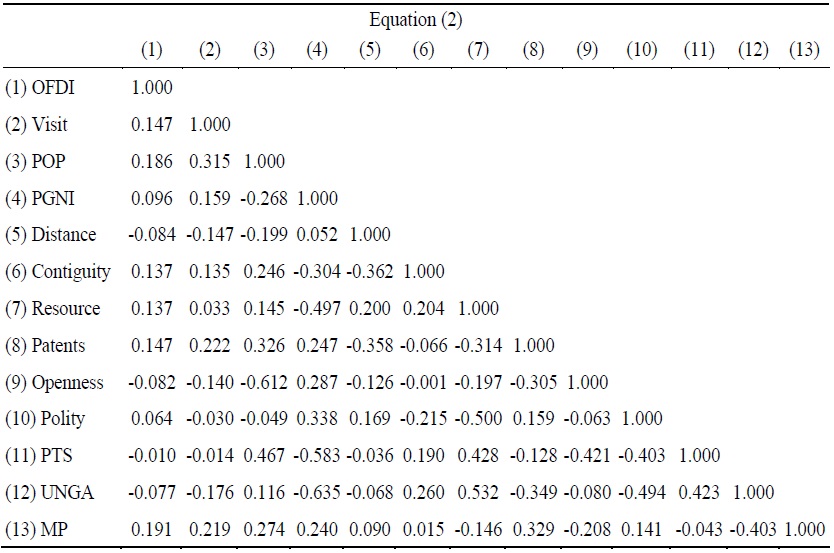

Table B3.

Correlation Matrix

Note: Equation (1) represents the FDI equation, and equation (2) indicates the Visits equation.

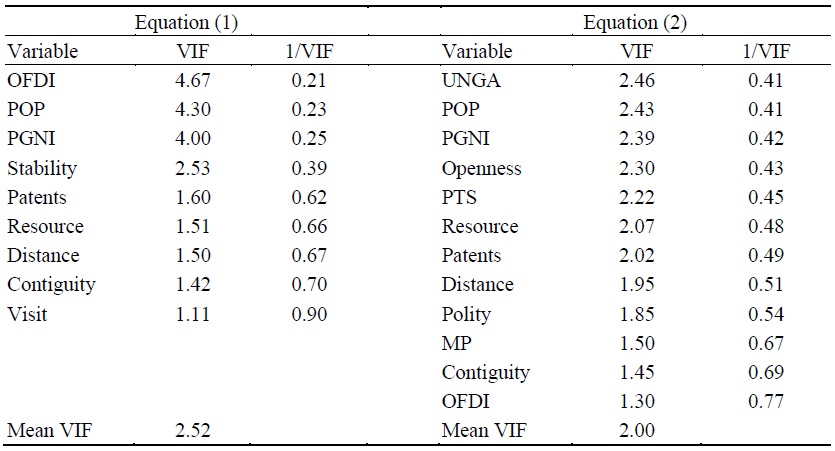

Table B4.

Variance Inflation Factor Test

Notes: 1) VIF = variance inflation factor. The VIF represents the extent to which the variance is inflated. In general, VIFs greater than 10 indicates significant multicollinearity. 2) Equation (1) represents the FDI equation, and equation (2) indicates the Visits equation.

References

-

Adam, A. and S. Tsarsitalidou. 2023. “Be My Guest: The Effect of Foreign Policy Visits to the USA on FDI.”

Review of World Economics 1-26.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00500-w -

Alesina, A. and R. Perotti. 1996. “Income Distribution, Political Instability, and Investment.”

European Economic Review , vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1203-1228.

-

Baidu. “经济外交.” Baidu Baike.

https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E7%BB%8F%E6%B5%8 E%E5%A4%96%E4%BA%A4/6928936?fr=ge_ala (accessed on February 24, 2024) -

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., and E. Voeten. 2017. “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data.”

Journal of Conflict Resolution , vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 430-456.

-

Bayne, N. and S. Woolcock. 2003.

The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiation in International Economic Relations . 2nd ed. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. -

Beaulieu, E., Lian, Z., and S. Wan. 2020. “Presidential Marketing: Trade Promotion Effects of State Visits.”

Global Economic Review , vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 309-327.https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2020.1792329

-

Bleaney, M., and A. Nishiyama. 2002. “Explaining Growth: A Contest Between Models.”

Journal of Economic Growth , vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 43-56.

-

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., and P. Zheng. 2007. “The Determinants of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment.”

Journal of International Business Studies , vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 499-518.https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400277

-

Cass, F. 2007. “Attracting FDI to Transition Countries: The Use of Incentives and Promotion Agencies.”

Transnational Corporations , vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 77-90. -

Chang, S.-C. 2014. “The Determinants and Motivations of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: A Spatial Gravity Model Approach.”

Global Economic Review , vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 244-268.https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2014.930670

-

Chen, M. X. and C. Lin. 2018. “Foreign Investment Across the Belt and Road: Patterns, Determinants, and Effects.”

World Bank Policy Research Working Paper , no. 8607.https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-8607 -

Chen, Y., Gunessee, S., and X. Hua. 2022. “Emerging Market Multinationals’ Pursuit of Strategic Assets Through Cross-Border Acquisitions.”

Research in International Business and Finance , vol. 63, no. 101792.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101792 -

Cornwell, C., Schmidt, P., and D. Wyhowski. 1992. “Simultaneous Equations and Panel Data.”

Journal of Econometrics , vol. 51. no. 1-2, pp. 151-181.

-

Deng, P. 2004. “Outward Investment by Chinese MNCs: Motivations and Implications.”

Business Horizons , vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 8-16.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-6813(04)00023-0

-

Deng, P. 2007. “Investing for Strategic Resources and Its Rationale: The Case of Outward FDI from Chinese Companies.”

Business Horizons , vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 71-81.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2006.07.001

-

Desbordes, R. 2010. “Global and Diplomatic Political Risks and Foreign Direct Investment.”

Economics and Politics , vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 92-125.

- Desbordes, R. and V. Vicard. 2005. “Being Nice Makes You Attractive: The FDI-International Political Relations Nexus.” Paper presented at the 9th Annual International Conference on Economics and Security, Bristol.

-

Dunning, J. H. 2000. “The Eclectic Paradigm as an Envelope for Economic and Business Theories of MNE Activity.”

International Business Review , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 163-190.

-

Fuchs, A. 2018. “China’s Economic Diplomacy and the Politics-Trade Nexus.” In van Bergeijk, P. A. G., and S. J. V. Moons. (eds.)

Research Handbook on Economic Diplomacy , pp. 297-314. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. -

Gueldry, M. and W. Liang. 2016. “China’s Global Energy Diplomacy: Behavior Normalization through Economic Interdependence or Resource Neo-Mercantilism and Power Politics?”

Journal of Chinese Political Science , vol. 21, pp. 217-240.

-

Harding, T. and B. S. Javorcik. 2012. “Developing Economies and International Investors: Do Investment Promotion Agencies Bring Them Together?”

World Bank Policy Research Working Paper , no. 4339.https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4339 -

Heath, T. R. 2016. “China’s Evolving Approach to Economic Diplomacy.”

Asia Policy , vol. 22, pp. 157-192.

-

Kodila-Tedika, O. and S. Khalifa. 2023. “Official Visits and Foreign Direct Investment.”

The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development , vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 1-27.https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2023.2175592 -

Kolstad, I. and A. Wiig. 2012. “What Determines Chinese Outward FDI?”

Journal of World Business , vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 26-34.

-

Lebovic, J. H. and E. N. Saunders. 2016. “The Diplomatic Core: The Determinants of High-Level US Diplomatic Visits, 1946-2010.”

International Studies Quarterly , vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 107-123.

-

Li, J. and Y. J. Choi. 2022. “Topic Analysis of Foreign Policy and Economic Cooperation: A Text Mining Approach.”

Journal of Korea Trade , vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 37-57.

-

Lin, F., W. Yan, and X. Wang. 2017. “The Impact of Africa-China’s Diplomatic Visits on Bilateral Trade.”

Scottish Journal of Political Economy , vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 310-326.

-

Marshall, M. G. and T. R. Gurr. 2020. “Polity5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018.” Center for Systemic Peace 2.

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1NHKR -

Medeiros, E. S. 2009. “The New Security Drama in East Asia: The Responses of US Allies and Security Partners to China’s Rise.”

Naval War College Review , vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 37-52. -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. “Bilateral Visits and Foreign Policy Initiatives.”

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC .https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ mfa_eng/ -

Moons, S. J. and P. A. G. van Bergeijk. 2017. “Does Economic Diplomacy Work? A Meta‐Analysis of Its Impact on Trade and Investment.”

The World Economy , vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 336-368.

-

Morisset, J. 2003. “Does a Country Need a Promotion Agency to Attract Foreign Direct Investment? A Small Analytical Model Applied to 58 Countries.”

World Bank Policy Research Working Paper , no. 3028.https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-3028 -

Nitsch, V. 2007. “State Visits and International Trade.”

The World Economy , vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1797-1816.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.01062.x

-

Okano-Heijmans, M. 2011. “Conceptualizing Economic Diplomacy: The Crossroads of International Relations, Economics, IPE, and Diplomatic Studies.”

The Hague Journal of Diplomacy , vol. 6, no. 1-2, pp. 7-36.

-

Park, G., and H. J. Jung. 2020. “South Korea’s Outward Direct Investment and Its Dyadic Determinants: Foreign Aid, Bilateral Treaty, and Economic Diplomacy.”

The World Economy , vol. 43, no. 12, pp. 3296-3313.

-

Polachek, S., Seiglie, C., and J. Xiang. 2007. “The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on International Conflict.”

Defence and Peace Economics , vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 415-429.

-

Ramasamy, B., Yeung, M., and S. Laforet. 2012. “China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Location Choice and Firm Ownership.”

Journal of World Business , vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 17-25.

-

Rana, K. S. 2007. “Economic Diplomacy: The Experience of Developing Countries.” In N. Bayne, N., and S. Woolcock. (eds.)

The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiations in International Economic Relations , pp. 277-296. Farnham: Ashgate. -

Rose, A. K. 2007. “The Foreign Service and Foreign Trade: Embassies as Export Promotion.”

The World Economy , vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 22-38.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00870.x

-

Stone, R. W., Wang, Y., and S. Yu. 2022. “Chinese Power and the State-Owned Enterprise.”

International Organization , vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 229-250.

-

Sun, C. and Y. Liu. 2019. “Can China’s Diplomatic Partnership Strategy Benefit Outward Foreign Direct Investment?”

China and World Economy , vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 108-134.https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12289

-

Wang, Y. and R. W. Stone. 2023. “China Visits: A Dataset of Chinese Leaders’ Foreign Visits.”

The Review of International Organizations , vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 201-225.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

-

Yakop, M. and P. A. G. van Bergeijk. 2011. “Economic Diplomacy, Trade, and Developing Countries.”

Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society , vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 253-267.

-

Zhang, J., Jiang, J., and C. Zhou. 2014. “Diplomacy and Investment: The Case of China.”

International Journal of Emerging Markets , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 216-235.https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-09-2012-0104

-

Zhang, X. and K. Daly. 2011. “The Determinants of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.”

Emerging Markets Review , vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 389-398.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2011.06.001

-

Zhen, B. 2010. “Protecting China’s overseas national interests in changing international circumstances: Experience of Western countries and what China should do.”

China International Studies , 21(March/April), pp. 80-97.