- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Citation

| No | Title |

|---|

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 28, No. 4, 2024. pp. 421-457.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2024.28.4.441

Number of citation : 0Assessing Policy-related Risk and Export Dynamics: Evidence from 16 Economies

|

Central University of Finance and Economics |

Abstract

This research examines the impact of policy-related risk (geopolitical risk, economic uncertainty, and political risk) on export performance. The data we used came from 16 leading economies between 1998 and 2022. We used fixed effect, two-stage least squares (2SLS), and generalized method of moments (GMM) regression analyses to see how different types of policy-related risk affect exports. The results show that geopolitical risk and economic policy uncertainty have a negative impact on export performance, while political stability has a positive effect. We divided the countries into East and West, developing and developed countries, and the results show different efficiency but the same impact on East and West. However, the result of developed and developing countries has a variation in the effect of geopolitical risk on exports; in developed countries, the geopolitical risk has a negative insignificant effect, while in developing countries, it has a significantly negative impact. The study contributes to the literature by providing a regional perspective on the influence of policy-related risks on export performance, offering valuable insights for policymakers and firms seeking to navigate the complexities of global trade amidst uncertainty.

JEL Classification: E60, F10, F14

Keywords

Policy-related Risk, Geopolitical Risk, Economic Policy Uncertainty, Political Risk, Export Performance

I. Introduction

Policy-related risks, such as geopolitical tensions, political instability, and economic policy uncertainties, significantly shape global trade and economic dynamics. These risks can stem from various sources, including armed conflicts, political disputes, and sudden changes in government policies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2017)1 has underscored the importance of these risks, highlighting that they pose substantial threats to the global economic outlook. For instance, armed conflicts and geopolitical tensions often lead to trade disruptions and the imposition of sanctions (Glick and Taylor, 2010). Similarly, geopolitical concerns have a direct impact on trade flows, as demonstrated by both theoretical and empirical evidence presented in the literature (Glick and Taylor, 2010; IMF, 2017).

The pervasive influence of geopolitical risk on trade, investment, and overall economic stability has attracted the attention of numerous scholars. Geopolitical risks shape the decision-making processes of corporate investors, central bankers, and financial experts, and they are often a focal point in media discussions (Caldara et al., 2018). States’ strategic use of geopolitical leverage to control and compete for territory can have detrimental effects on trade and investment (Pollins, 1989; Balcilar et al., 2018). These risks can influence various economic parameters, such as currency exchange rates, government fiscal policies, and central bank monetary policies (Engel, 2014; Mueller et al., 2017). Moreover, income inequality within a nation can be affected by the interplay of these economic, financial, and political risks, as demonstrated by studies on income distribution patterns (Lee and Lee, 2018; Chiu and Lee, 2019; Lee et al., 2021).

Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) represents another critical dimension of policy-related risks. EPU occurs when there is ambiguity regarding the direction and strength of monetary policy, causing uncertainty among businesses and individuals about future economic conditions (Le and Zak, 2006; Gulen and Ion, 2016). This uncertainty can significantly impact macroeconomic factors. For example, a sudden increase in short-term EPU in China can stifle economic growth, investment, and consumption (Huang and Guo, 2015; Hu and Liu, 2021). EPU can also deter foreign capital inflows and alter capital movement patterns, particularly in emerging economies (Xiaofen et al., 2018). Furthermore, EPU has been shown to reduce employment rates, especially in firms with different ownership structures (Yang M, 2018). Trade security policy uncertainty is another aspect of EPU that can inhibit investment by increasing cash costs and reducing marginal returns (Carballo et al., 2018).

Political risks, including geopolitical and economic policy uncertainties, are crucial determinants of a nation’s financial stability. Political instability, often arising from a combination of social, political, cultural, and economic factors, can severely impede economic progress by creating uncertainty about future policy directions (Tabassam et al., 2016; Gurgul and Lach, 2013; Murad and Alshyab, 2019). This instability can lead to suboptimal macroeconomic policies, frequent policy changes, and lower economic growth rates (Aisen and Veiga, 2013; Soybilgen et al., 2019). The negative impact of political instability on exports has been documented in various contexts, such as Egypt (Khalil et al., 2020). Hence, the policy-related risk mechanism is still an empirical question with a literature gap.

Many scholarly studies have focused on the effects of actual political or geopolitical disruptions and economic uncertainty on economic growth, trade flow, tourism, etc. Nevertheless, these occurrences exemplify a single aspect of the broader range of global volatility. These risks are expected to have an impact on exports. However, there is a lack of research on the effects of policy-related risk on the export of goods and services. Our study aims to fill the gap of research and investigate the impact of country-specific GPR, Political Risk, and economic policy uncertainty indices on export relationships of 16 developed and developing countries. This study builds upon the research conducted by Caldara et al. (2018), which focused solely on examining the overall trade of the United States, including both total exports and imports. We extend the research of Lee et al. (2021) on Policy-related risk and corporate financing behaviour; in our paper, we use the same policy-related risk data for a country base and its effect on the export of goods and services. Our analysis focuses on export performance because the countries in our data set comprise 16 leading economies, many of whom are large trade partners. This idea means that exports from one country often represent imports for another country. To avoid redundancy and because import performance is closely related to export dynamics in our sample, we focus on exports and capture the direct outward economic impact of policy-related risks. To balance our analysis and account for export performance in terms of trade, we include import performance as a control variable in our empirical models. This enables us to identify the impact of policy-related risks on exports and control for any spillover effects through the import side.

This research uses annual data from 1998 to 2022 to analyze how different policy risks influence export decisions. It makes several key contributions to the existing literature. First, it extends the current body of knowledge by assessing the impact of multiple risk indicators on exports. It offers a more comprehensive evaluation than prior studies that predominantly focused on single measures, often using global geopolitical risk data. In contrast, this study utilizes country-specific geopolitical risk data, providing more precise insights into the effects of country-specific rather than global risks. Additionally, we incorporate country-level economic uncertainty data and political risk data to identify which type of risk impacts exports more significantly. This approach allows the study to cover three distinct dimensions of risk.

Second, various diagnostic tests are conducted for the empirical analysis to ensure data validity and model robustness. We employ three models: Fixed Effects, 2-stage Least Squares (2SLS), and the 2-step Generalized Method of Moments (GMM). The use of multiple models aims to validate our results comprehensively. Diagnostic tests indicated the presence of endogeneity in the data, which led us to adopt the 2-step GMM model to address this issue effectively.

Third, we conducted a robustness check by dividing the countries into two groups: first, according to geography, Western and Eastern countries; in addition, we split countries according to the economic size of developed and developing countries; furthermore, we divided the countries according to oil export and importing countries. Additionally, we assess the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on export performance and risk. The findings reveal that while economic policy uncertainty and geopolitical risk have a negative effect on exports, political stability has positively influenced export performance. The analysis also shows distinct regional differences, with both geopolitical risk and economic policy uncertainty adversely affecting exports in Western and Eastern regions, albeit with varying coefficients as well; as in developed and developing countries, economic policy uncertainty and political stability show the same effect with different coefficient like west and east countries but Geopolitical risk in developed countries shows insignificant effect and in developing countries geopolitical risk effect negative significant impact on export. The results of oil-exporting and oil-importing countries show the same effect as our main analysis with different coefficients.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed literature review. Section 3 outlines the data sources and methodological approach used in the study. Section 4 presents the empirical findings and discusses their implications. Finally, Section 5 concludes with key insights and suggestions for future research.

1)

II. Literature Review

1. Theoretical Framework

Policy-related risks and export dynamics are increasingly relevant in today’s globalized economy, mainly through the perspective of institutional theory. The institutional theory posits that the behaviour of firms is significantly shaped by the regulatory and normative frameworks within which they operate. Economic and policy uncertainties can severely hinder export investment. Research indicates that foreign income and trade protection uncertainty can dampen firms’ willingness to engage in international markets (Tang and Buckley, 2020). Darby et al. (2020) demonstrate that uncertainty about trade policies and foreign economic conditions interacts in ways that significantly dampen export investment, especially during periods of heightened demand volatility. Their findings highlight that trade agreements can mitigate these uncertainties, providing a more stable environment for exporters. Specifically, they note that US exports to non-preferential markets would have been approximately 6.5% higher had trade agreements been in place, underscoring the value of institutional commitments in stabilizing trade relationships (Shabir et al., 2021).

Moreover, the dynamics of export behaviour are influenced by the institutional context in which firms operate. Economies with robust institutions tend to exhibit more stable export dynamics, as firms can navigate uncertainties more effectively through established regulatory practices and support systems. In contrast, firms in economies with weaker institutions may face greater vulnerability to policy shocks, leading to erratic export performance (Sharma and Khanna, 2024). The interaction between economic and policy uncertainty can amplify risks, as government interventions intended to address economic downturns may inadvertently increase policy uncertainty, further complicating the export landscape (Aralica et al., 2018). The importance of trade agreements in this context cannot be overstated. They serve as a mechanism to reduce uncertainty by providing predictable frameworks for trade, thereby encouraging firms to invest in exports. This is particularly critical during economic downturns when uncertainty tends to peak (Dong et al., 2022). The empirical evidence suggests that strong institutional frameworks and trade agreements play a vital role in mitigating the adverse effects of economic and policy uncertainties, fostering a more conducive environment for export activities (Zhang and Hu, 2023). Strong institutions and effective trade agreements can significantly alleviate the negative impacts of economic and policy uncertainties, promoting a more stable and predictable environment for international trade.

2. Empirical Framework

(1) Political risk and export

Melitz’s model involves the analysis of the effects of political instability on the foreign market entry of any given company. In line with Melitz’s theory, exporting enterprises differ in terms of the baseline level of productivity and fixed costs. According to this model, trade liberalization leads to an internal reallocation of resources since poor firms leave markets and efficient firms expand and penetrate international markets. The model also implies a negative relationship between potential earnings and political instability since the latter increases the costs associated with production. In politically unstable environments, the inefficient producers produce at very low-efficiency rates and, in effect, get purged out of the market by superior producers who can now buy the resources left behind by the less efficient producers. These remaining firms enjoy a larger market share with increased efficiency, making them more competitive. Thus, these more productive companies earn higher incomes and are in a better place to penetrate foreign markets.

On the other hand, inefficient companies are limited to domestic sales due to their lesser efficiency than their rivals. Hosny (2017) employed firm-level data to show that perceived political instability reduced sales and employment growth. This research was the first to show causality between PI and corporate performance. A study utilizing the data collected from the Tunisian Enterprise Survey noted political risks as an issue of concern, especially in the tourism sector, enterprises with fewer employees, and exporters (Matta et al., 2018). They also observed that PI has damaged the growth of companies in Tunisia after the social upheavals that accompanied the Arab Spring.

According to Olney (2016), it was established that corruption compels firms away from market selectivity. This process can be linked to the high costs of operation incurred due to corruption, which hampers many firms’ ability to compete in the domestic market. As with corruption, political instability may have the same impact on the behaviour of the companies since both point to issues of poor governance and lead to a rise in operational costs. Fredriksson and Svensson (2003) offered a model that shows the relationship between political influence, corruption, and policy. The study revealed that in most cases, political influence has a detrimental effect on the stringency of environmental standards/regulations wherever the corruption index is low.

On the other hand, the propensity of corruption in a country leads to political integrity, increasing such legislation’s rigour. Fosu (2003) explored how political instability reduced exports and economic growth in sub-Saharan countries, spanning from 1967 to 1986. This also has the effect of linking political instability to either the capabilities of a firm to export as well as political connections. Whereas, in conditions of higher political risk, the formal structures may, in many ways, dilute so that those companies that have direct access to political executives can work their way through the bureaucracy with greater ease. Such activities include export licenses, import, and quotas given to the business or company. Such connections offer firms a competitive edge, mainly when foreign markets are even more attractive than domestic ones. Thus, international expansion in politically unstable regions will naturally go to companies with some form of political clout over competing firms.

Many studies have found significant effects of political instability on export activities in different sectors and regions. Urbanization in importing countries can also make political ties more critical, as these ties can destabilize food exports by raising tariff and non-tariff barriers (Zhou et al., 2023). Geopolitical instability negatively impacts trade in Russia, primarily through the mediation of reducing foreign direct investment (FDI) (Talamanov, 2024). Like in Pakistan, political instability influences international trade and investment negatively, and this also curbs exports in the short run (Qadri et al., 2020). On the contrary, stronger political institutions have led to the growth of export activities in reducing transaction costs and decreasing the risks of doing business as the trade between Iran and the West Asia partners proves where the better political institutions have had a positive impact on exports in different commodity groups (Nagheli and Maddah, 2017).

(2) Geopolitical risk and export

The effect of geopolitics on international business has attracted much interest in the last few years. This review, therefore, synthesizes information from different scholarly sources to give a clear account of this rather complicated relationship. Gupta et al. (2019) employed a gravity model for trade flow data for 164 countries from 1985-2013. Based on their research, they conclude that higher geopolitical risks have an adverse impact on trade flows, thus implying that these risks should be taken into account when studying the nature of international trade. Caldara and Iacoviello (2022b) constructed an index of Geopolitical Risk (GPR) using news data and showed that geopolitical risk damages investment, employment, and economic activity, especially for export-dependent firms. Góes and Bekkezrs (2022) stressed the role of the integrated and connected international trade system in avoiding possible welfare losses in geopolitical tensions and economic isolation.

Furthermore, Soybilgen et al. (2019) analyzed the effects of geopolitical risks on developing countries’ economic growth, and it was found that geopolitical risk has a negative impact on the GDP growth rates. In the related research by Shi et al. (2022), the authors focused on countries’ dependence patterns in the cobalt trade and the effect of country risk. Their studies establish that import source risk and market concentration are high among importers and exporters, whereas geopolitical risk reduces importers’ performance but increases exporters’ performance. Kim and Jin (2023) and Jin and Shin (2022) have also looked into the multifaceted interaction between geopolitical risk and international trade with special reference to export-led economies. Choi and Oh (2022) extended the analysis of the changing trade politics concerning Korea and Japan to the global escalating tensions and trade wars, demonstrating the significance of the geopolitical threats for trade politics. Additionally, Khan et al. (2022) explored the relationship between geopolitical risk and defence spending in various countries, highlighting how geopolitical tensions influence military budgets and global trade. Furthermore, Khan et al. (2022) studied the impact of geopolitical risk on the stability of the Turkish financial system, emphasizing the repercussions of regional and global geopolitical risks on trade and financial markets.

(3) Economic uncertainty and export

Macroeconomics involves using governments’ policies and plans to control and direct the economy’s performance. Volatility is a key element of economic cycles, which indicates that the government cannot clearly define what its actions and plans for the future hold for the effectiveness of financial measures. This generates uncertainty for economic agents about policy changes, the timing of such changes, and their possible implications (Le and Zak, 2006; Gulen and Ion, 2016) and the fundamental institutional characteristics of the economy and their evolution. Some occurrences that have led to high economic policy uncertainty include the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and geopolitical conflicts (Bloom, 2009). As soon as significant economic shocks appeared, many attempts were made to assess the impact of uncertainty on the economy (Born and Pfeifer, 2014; Leduc and Liu, 2016; Basu and Bundick, 2017; Kamara and Koirala, 2023).

For instance, Greenland et al. (2019) employed a stochastic frontier gravity model to analyze the nature of the country risk and the foreign trade in the Belt and Road countries. They concluded that reducing risk increases the bilateral trade, suggesting the initiative's efficacy. There is an excellent focus on macroeconomic factors such as production, inflation, unemployment, interest rates, and bank assets, especially in analyzing how uncertainty influences economic fluctuations. Azzimonti and Talberst (2014) opine that political polarization is higher in emerging than developed economies, implying that monetary policy instability results from political instability. Policy changes always bring enormous economic risks at the international and regional levels when implementing policy changes. Uncertainty may be exacerbated by a lack of clarity in macroeconomic policies and frequent changes in the same, thus affecting investment, employment, economic growth, and the stock markets’ performance. Higher uncertainty can also have negative impact on the financial performance. The studies by Liu and Zhang (2020) and Baker et al. (2016) show that economic policies should be well-coordinated and stable to support further economic growth. Nevertheless, little research has been done on economic policy uncertainty’s implications on critical areas like trade.

This paper aims to fill this gap by exploring the possible correlation between economic policy uncertainty and the global export industry. We review the literature on geopolitical risk, political risk, and economic policy uncertainty, highlighting their influence on global export activities through the lens of the new risk index. Our analysis covers a more extended period and a broader range of countries than previous studies, utilizing various panel data econometric techniques. Moreover, our research is uniquely focused on one specific trade sector: exports. This approach enables us to draw more precise conclusions regarding the impact of these risks on export dynamics.

III. Research Methodology

1. Data and Samples

We use 25 years of data from 16 developed and developing countries, including Australia, Canada, Chile, China, Brazil, India, Germany, Japan, Italy, South Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, United States, United Kingdom, Russia, and Sweden. The nations chosen for study are selected based on economic significance, trade policies, industrial concentration, geopolitical considerations, and various views. The US, China, and the European Union, significant participants in global commerce, have unique trade policies that directly affect export activity. Research is especially crucial for countries with specialized businesses or sectors, such as manufacturing or natural resources. Geopolitical factors, such as alliances and trade agreements, influence export dynamics.

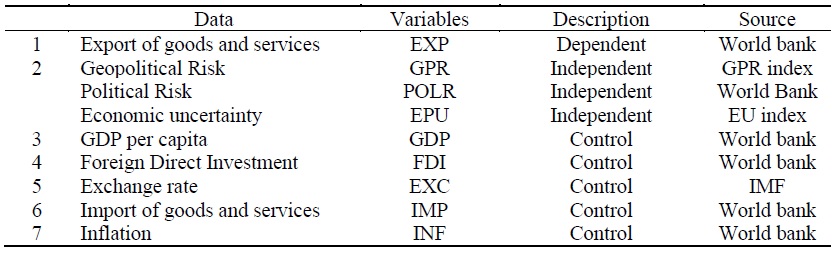

In this study, dependent (export of goods and services) and control variables were yearly data from the World Bank2. The data in this study covers from 1998 to 2022. We use three specific indicators to describe the risk associated with policies: policy-related uncertainty, geopolitical risk, and political risk. This study employs the GPR data from the GPR index3 formulated by (Caldara and Iacoviell, 2022) to quantify geopolitical risk levels. This index combines information on terrorist operations and other geopolitical conflicts to measure global uncertainty ultimately. The GPR data we downloaded were monthly, and we calculated and made them yearly. We use the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU)4 Index, created by (Baker et al., 2016) to measure policy uncertainty. Our measure of political risk is obtained from the World Bank. This guide evaluates socio-economic aspects and political stability in different nations. Other control variables are also collected from World Bank data except one of the control variables, which is the exchange rate we get from the IMF database. Table 1 exhibits the data discretion steps during the collection of datasets for this research.

2. Model Specification

(1) Effect of political risk on export

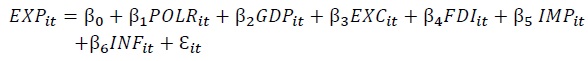

An econometric model for analyzing the impact of geopolitical risks on export is specified as follows:

Where

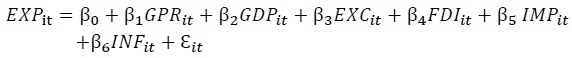

(2) Effect of geopolitical risk on export

An econometric model for analyzing the impact of political risks on export is specified as follows:

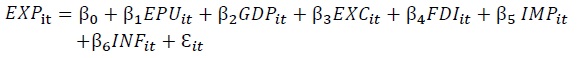

(3) Effect of economic policy uncertainty on export

An econometric model for analyzing the impact of Economic policy Uncertainty on export is specified as follows:

Where

3. Data Analysis Technique

A descriptive statistics analysis examines a dataset’s normal distribution. Pearson’s correlation analysis investigates the direction of the link between variables. Afterward, each variable’s variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis is performed to detect multicollinearity. The research employs a basic linear regression approach, namely ordinary least squares (OLS), to examine the predicted correlations. Further, heteroskedasticity, multicollinearity, and autocorrelation were assessed using several diagnostic tests. Subsequently, three further sophisticated regression approaches are used to tackle endogeneity and autocorrelation concerns: step generalized method of moments (GMM), fixed-effect, and 2SLS regression models. Anser et al. (2020) also used 16 countries’ data from 1990-2024 and also used 2-step GMM for their study of Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures. These strategies are specifically developed to tackle the issues of endogeneity and autocorrelation. As a last step, we will conduct a robustness check to evaluate the reliability of our results. This involves testing the stability of our findings by utilizing alternative measurements for the dependent variable and examining the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on our model.

2)

3)

4)

IV. Empirical Results

1. Descriptive Statistics

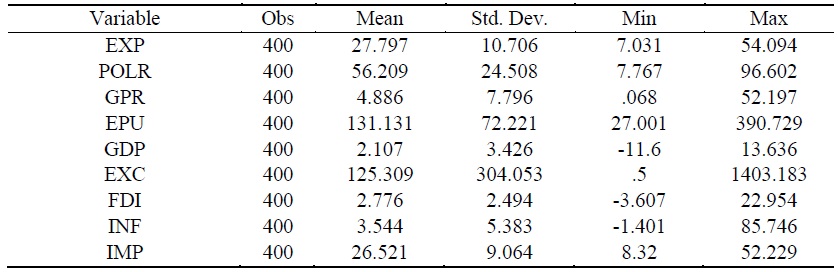

In Table 2, the mean figure for the export performance variable is 27.797, with moderate variability with a standard deviation of 10.706. Over the 25 years, however, trends generally show all countries experiencing an upward trend in export performance, punctuated by periodic declines, especially during global economic crises, most notably the 2008 financial crisis. Some of these suggest that export performance is increasing over time, while some indicate that export performance is vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks.

Of the many examined factors, Political Risk, with its average value of 56.209 and significant variability (standard deviations of 24.508), has the most significant fluctuations over the observed period. Some countries have become more politically stable, but many have become more politically unstable, especially when it conflicts with values or a change of government. The trend analysis reveals that some countries are converging toward more minor political risks while others continue to be plagued by instability.

The Geopolitical Risk index has a mean of 4.886 and has a right-skewed distribution where its range is (0.068 to 52.197). In the long run, the GPR index displays sharp changes in spikes in correspondence to significant geopolitical events, like war conflicts: the 2003 Iraq War, the 2011 Arab Spring, the 2014 Russia-Ukraine crisis, etc. The index is relevant to export performance as these spikes coincide with heightened global trade and investment uncertainty.

Economic Policy Uncertainty shows substantial variation across countries and over time, with a wide dispersion (standard deviation of 72.221) and an average of 131.131. Changes in these trend series tracked reported heightened uncertainty surrounding important global and regional events, including the 2008 global financial crisis, Brexit, and trade disputes in recent years. The variability highlights the need to control policy uncertainty in analyzing export performance.

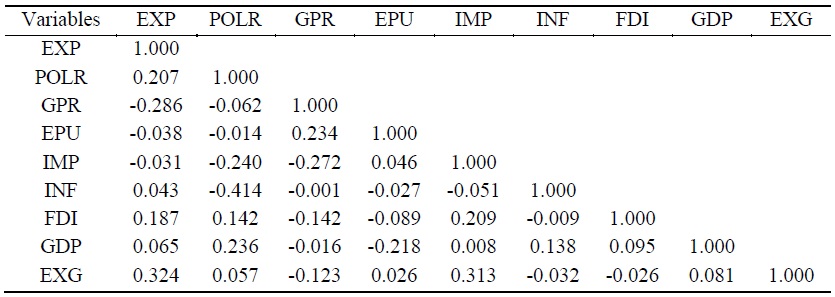

2. Correlation Matrix

The correlation matrix in Table 3 highlights the relationships between key variables related to export dynamics and various policy-related risks. The correlation between export levels (EXP) and political risk (POLR) is relatively weak at 0.207, indicating a minor positive association. This suggests that export levels tend to rise slightly as political risk increases. Conversely, geopolitical risk (GPR) shows a moderate negative correlation with exports (-0.286), suggesting that higher geopolitical risks are associated with lower export levels. Economic policy uncertainty (EPU) is weakly correlated with exports (-0.038), indicating a minimal negative relationship, which suggests that fluctuations in policy uncertainty have a negligible direct effect on exports. Meanwhile, imports (IMP) correlate slightly negatively with exports (-0.031), reflecting a limited inverse relationship. Inflation (INF) shows a very slight positive correlation with exports (0.043), implying that inflation has an almost negligible impact on export levels.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) demonstrates a slight positive correlation with exports (0.187), suggesting that higher levels of FDI are modestly associated with increased export activities. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth shows a minimal positive correlation with exports (0.065), indicating that economic growth slightly supports export levels. The exchange rate (EXG) strongly correlates positively with exports (0.324), suggesting that a favourable exchange rate is significantly associated with higher export levels. Among the other relationships, political risk (POLR) negatively correlates with inflation (-0.414), indicating that higher political risk tends to be associated with lower inflation rates. Geopolitical risk (GPR) has a weak negative correlation with both political risk (-0.062) and imports (-0.272). At the same time, it is positively associated with economic policy uncertainty (0.234), suggesting that geopolitical tensions tend to increase policy uncertainty. Similarly, economic policy uncertainty (EPU) is negatively correlated with GDP growth (-0.218), showing that higher uncertainty negatively impacts economic performance. The correlation matrix provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between export levels, various risks, and macroeconomic factors, highlighting how different risks and economic conditions interact to influence export dynamics.

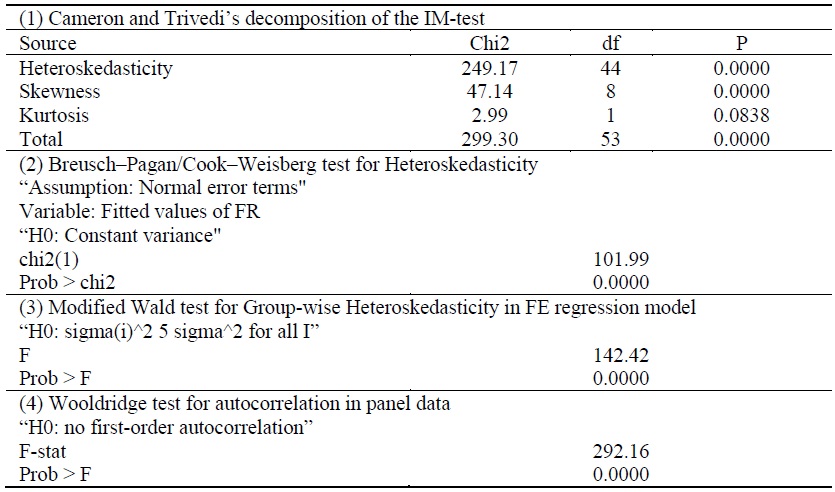

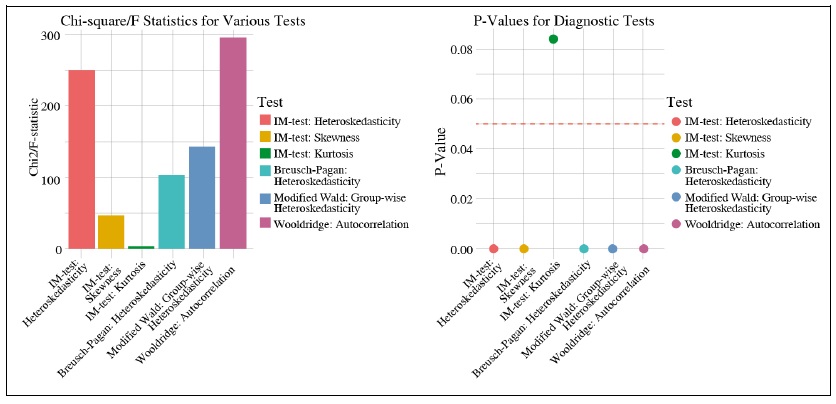

3. Diagnostic Testing

The findings of many diagnostic examinations are displayed in Table 4 and Figure 1. The breakdown of the Inoue-Matsusaka (IM) test conducted by Cameron and Trivedi indicates chi-square values of 47.14 for skewness, 249.17 for heteroskedasticity, and 2.99 for kurtosis, all of which have p-values < 0.0838. The results decisively refute the null hypotheses of equal variance, symmetrical distribution of residuals, and normal kurtosis, thereby revealing the existence of heteroskedasticity in the data. Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test yields a chi-square value of 101.99, with a p-value less than 0.0001, confirming the presence of heteroskedasticity in the model’s residuals. The Modified Wald test detects heteroskedasticity in the fixed-effects regression model by identifying inconsistent variances across groups. In addition, the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data produces an F-statistic of 292.16 with a p-value of less than 0.0001, showing the existence of first-order autocorrelation. The research suggests using more advanced econometric approaches, such as fixed effects, two-stage least squares (2SLS), and generalized method of moments (GMM), to address and perhaps rectify the biases identified in the data.

4. Baseline Regression

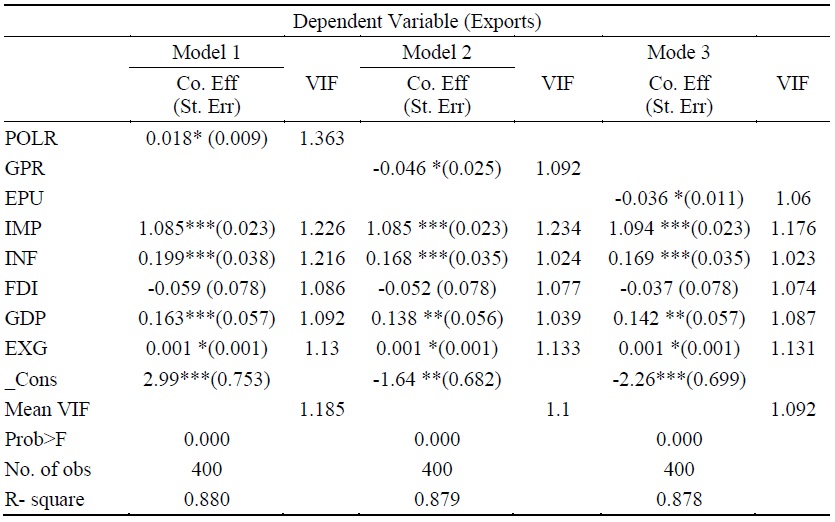

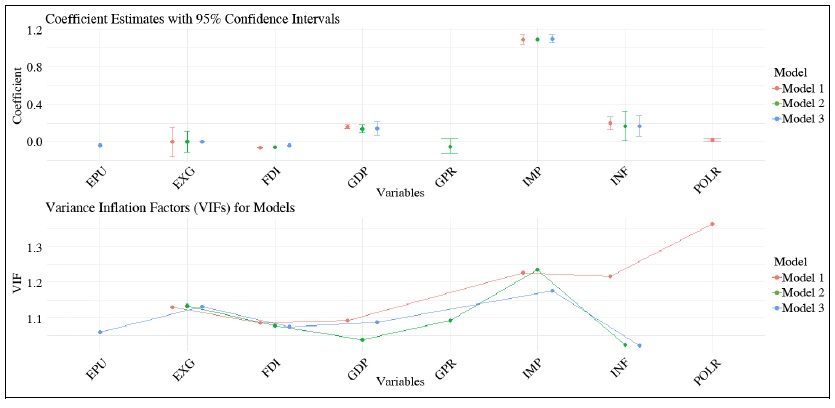

Table 5 and Figure 2 present the findings of an econometric study in which the variable being studied is Exports. The study has three models, each displaying coefficients, standard errors (in parentheses), P-values, and variance inflation factors (VIF) for several explanatory variables. The findings of model 1 indicate that a one-unit rise in POLR is associated with a 0.018 unit increase in exports, indicating a positive correlation. The asterisk indicates a statistically significant p-value, suggesting a dependable positive effect of POLR on exports. The presence of an asterisk (*) next to the coefficient indicates that the variable has achieved statistical significance at a specific level, often 0.05 or 0.10. Since there is a single asterisk, it may suggest statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

According to Model 2, GPR and exports have a negative relationship. Specifically, for every one-unit rise in GPR, exports fall by 0.046 units. The importance of this variable indicates that the negative impact is statistically significant in this model. The asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance at a confidence level 0.05. The results of the Model 3 suggest that an increase in Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) hurts exports. Specifically, a one-unit rise in EPU leads to a fall in exports by 0.036 units. Once again, the asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance, most likely at 0.05.

Regarding the R-square value: The data’s fit to the statistical model is shown by a value of around 0.880, demonstrating a significant amount of explained export variability based on the independent variables. The P-value of the F-test is extremely low (0.000), showing that the models are statistically significant. The mean VIF value indicates the presence of considerable multicollinearity in the models. Our model findings suggest the absence of substantial multicollinearity in the model.

5. Main Analysis Results

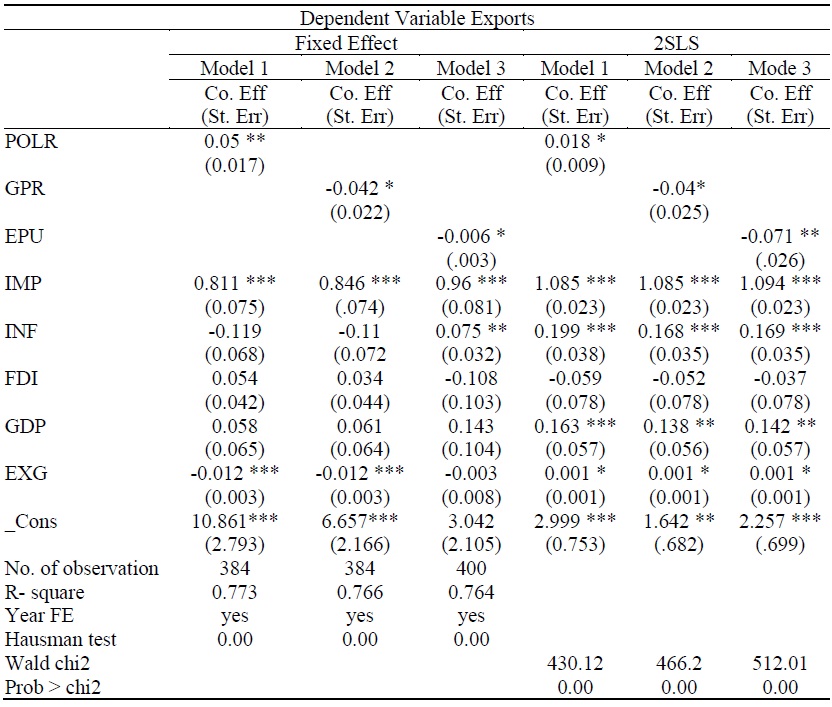

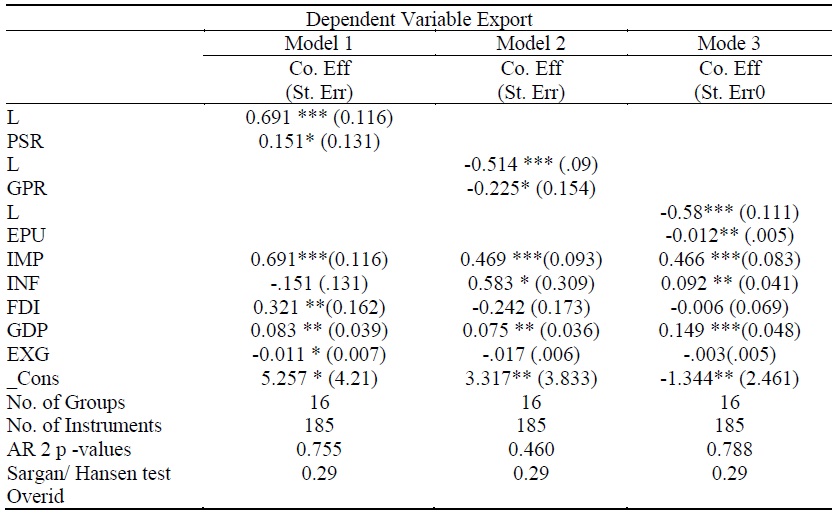

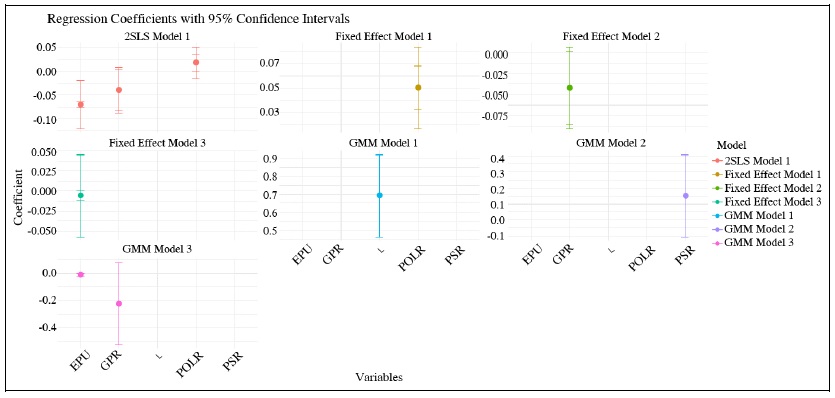

Table 6, 7, and Figure 3 analysis results involve utilizing various regression models, including Fixed Effects, Two Stage Least Squares (2SLS), and Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), in a two-step process to obtain the findings. These models are utilized to examine the impacts of different predictors on exports, defined as the dependent variable. The lagged variable, denoted as L, affects exports differently in various models. As an illustration, it exhibits a substantial positive coefficient in Model 1 of the Generalized technique of Moments (GMM) 2-step approach. At the same time, it demonstrates a notable negative impact in the Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) technique. This indicates that the influence of previous values on present exports is substantial, but it differs depending on the specific model being used. The impact of each variable on exports is measured by its coefficient, while the standard error indicates the accuracy of these estimations. The level of significance is indicated by stars, with three stars (***), two stars (**), and one star (*) representing p-values less than 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, respectively. The fixed effect models have high R-square values, exceeding 0.76, indicating a solid fit. This suggests that the models can explain a significant percentage of the export variability. The Hausman test yielded statistically substantial findings (p = 0.00), indicating that these models should use fixed effects instead of random effects. The Wald chi-square statistics exhibit a high significance level across all the models, suggesting that the models are statistically significant.

The p-values of AR 1 and AR 2 in GMM models are used to assess the presence of autocorrelation in the residuals. If these p-values are more significant than 0.05, it indicates no autocorrelation issues. The Sargan/Hansen tests provide p-values close to 0.29, indicating that the instruments employed in the GMM models are valid. Model 1: Using fixed effects, the coefficient of POLR is 0.05, with a standard error of 0.017. It is statistically significant at the 5% level, denoted by **. These findings indicate that exports typically rise when there is more excellent political stability and a lack of violence. A positive coefficient suggests a beneficial effect on the dependent variable export. According to the 2SLS model, there is a positive but small effect of a 1-unit rise in POLR on exports, resulting in a 0.018-unit gain. This association has statistical significance. Within the GMM model, the coefficient has a positive and significance value of 0.151 at a 10% level. This implies that the positive association may hold consistently across various estimate strategies. The study of Fosu (2003) on political instability and export performance in sub-Saharan Africa showed a negative relationship between Political instability and export performance.

Model 2: The GPR coefficient is -0.042 with a standard error of 0.022, and it is statistically significant at the 10% level (*). The presence of a negative coefficient indicates that GPR tends to decrease exports. The presence of a negative sign signifies a reciprocal correlation. A negative coefficient in both 2SLS (-0.042) and GMM (-0.514) models indicates that a rise in GPR is correlated with a decline in exports. This impact is statistically significant, although the confidence level in the GMM model is slightly lower. The adverse consequences suggest that more stringent government policies (perhaps perceived as regulatory or restrictive measures) might impede export efforts. These findings indicate that countries with more geopolitical risk export less in volume. Shi et al. (2022); Wang et al. (2021) also showed there is a negative relationship between GPR and trade.

Model 3: The fixed effect estimation shows that the coefficient of EPU is -0.006, with a standard error of 0.003. This coefficient is statistically significant at the 10% level, as indicated by the asterisk (*). This suggests that higher levels of economic policy uncertainty are linked to modest declines in exports, albeit the magnitude of this effect is relatively minor. A negative coefficient in the 2SLS model (-0.071) indicates that higher levels of economic policy uncertainty negatively impact exports. The significance of this link is that increased uncertainty potentially hinders export activity.

In contrast, the GMM model demonstrates a significant negative coefficient (-0.012) at a 10% significance level. This suggests that more uncertainty is associated with decreased exports in some situations. Greenland et al. (2019) paper also showed a negative impact of policy uncertainty on exports.

6. Robustness Check

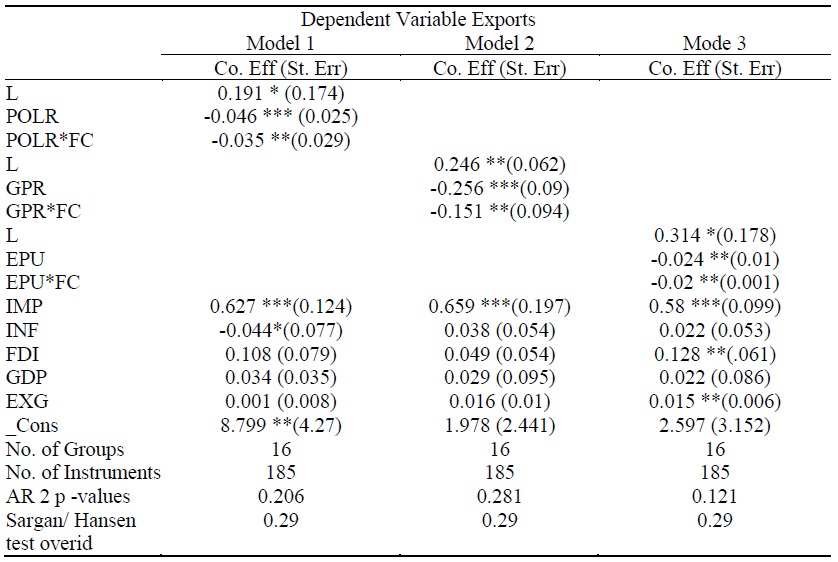

(1) Financial crisis impact

Table 8 examines the impact of the financial problems in 2008 on the models. A binary variable indicates the effect of the crises, with 0 representing the years before and 1 representing the years after the crises. The negative coefficients of the interaction terms (POLFC, GPRFC, and EPUFC) suggest that they have a detrimental influence on exports, particularly during crises. PSR*FC (POLR and FC interaction): A negative coefficient (-0.035) indicates that during financial crises, the Adverse Effect of POLR on exports is intensified. The statistical significance of this interaction (p < 0.01) suggests that financial crises greatly enhance the adverse impact of policy instability on exports.

The interaction term GPR*FC, which represents the interaction between GPR and Financial Crisis, has a negative coefficient in Model 2, similar to the PSR*FC interaction term. It suggests that government measures have an increasingly detrimental effect on exports during financial crises. The significance threshold (p < 0.05) is significantly less robust than PSR*FC but still suggests a significant impact. The study examines the interaction between Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) and Financial Crisis. The interaction term in question has negative coefficients in all models, suggesting that the negative impact of economic policy uncertainty on exports is amplified during financial crises. The constant statistical significance across models (p < 0.05) highlights financial crises’ ability to magnify uncertainty’s adverse effects on export efforts. This indicates that the financial problems have decreased the export. In the robustness check models, we use the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), which is more resilient, to tackle possible endogeneity problems.

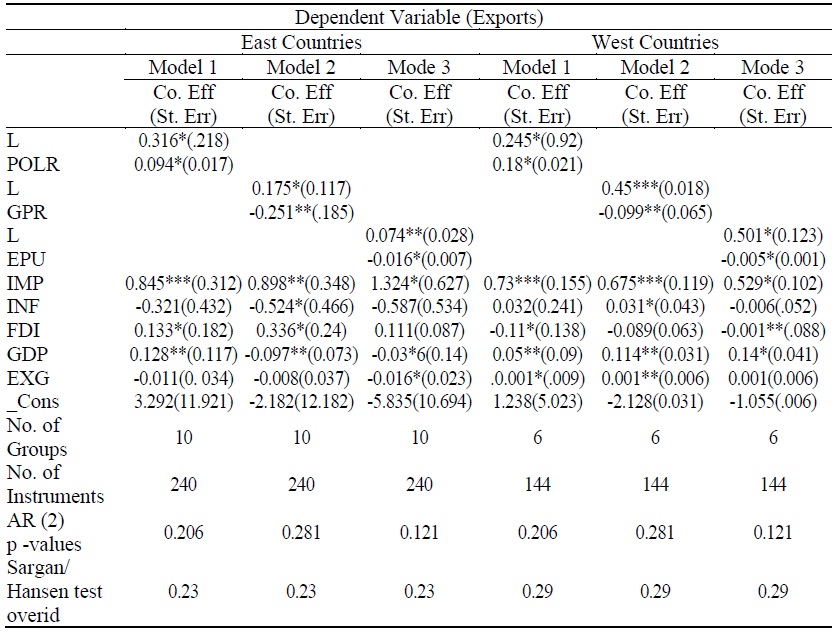

(2) Regional effect

Table 9 and Figure 4 display GMM regression findings for export behaviour, with separate analyses conducted for nations classified as “East”(China, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, Brazil) and “West.”(Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and the United States) Each model appears to incorporate distinct explanatory variables with their corresponding coefficients, standard errors, and various metrics of model validity, such as autocorrelation and overidentification tests. POLR (Political Risk) in Eastern Countries.

In Model 1, the POLR variable has a significant positive correlation of 0.094, indicating that an escalation in political risk is linked to a rise in exports. This suggests that businesses in Eastern countries may increase their exports to reduce uncertainties or risks within their domestic market. It could also result from specific industries, such as commodity sectors, which tend to export more when domestic instability causes the local currency to depreciate. In Western countries, the POLR variable also has a significant positive correlation of 0.18, indicating that an escalation in political risk is linked to a rise in exports.

Model 2 GPR (Geopolitical Risk) With Eastern Countries, the -0.251 coefficient shows a negative and significant coefficient for GPR, suggesting that increased geopolitical risks result in lower export levels. Geopolitical tensions may result in temporary surges in certain exports, such as military equipment or critical resources. Western nations: Conversely, the GPR exhibits a noteworthy negative coefficient of -0.099 in Model 2. This implies that higher geopolitical risk levels lead to reduced exports. This may be attributed to trade interruptions, heightened trade restrictions, or overall market volatility discouraging company and trade operations.

In Model 3 Eastern countries, EPU indicates a combination of positive and negative impacts. The coefficient is slightly negative but statistically significant, with a value of -0.016. The conflicting signals may indicate diverse reactions to policy uncertainty across different sectors or periods. Specific industries may choose to postpone exports owing to the uncertainty, while others may opt to expand exports in expectation of negative domestic policies. In Western countries, the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) variable is only shown to be statistically significant in Model 3, where it has a minor negative coefficient of 0.005. The limited effect implies increased economic policy uncertainty leads to a modest export decrease. Eastern nations sometimes boost their exports to mitigate the impact of heightened dangers, maybe to safeguard against uncertainties inside their borders. Western countries are particularly susceptible to geopolitical risks due to their highly interconnected and stable economies, which are easily affected by disturbances in international relations.

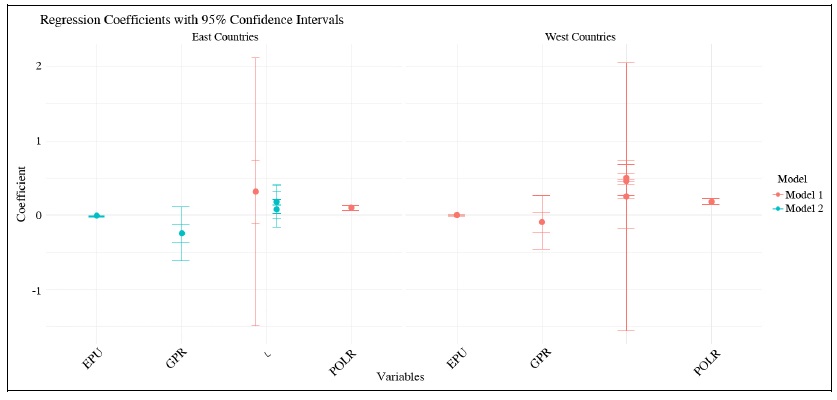

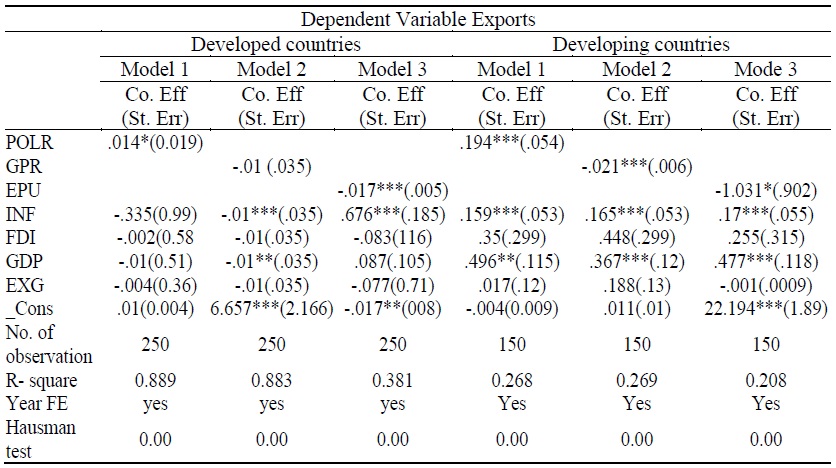

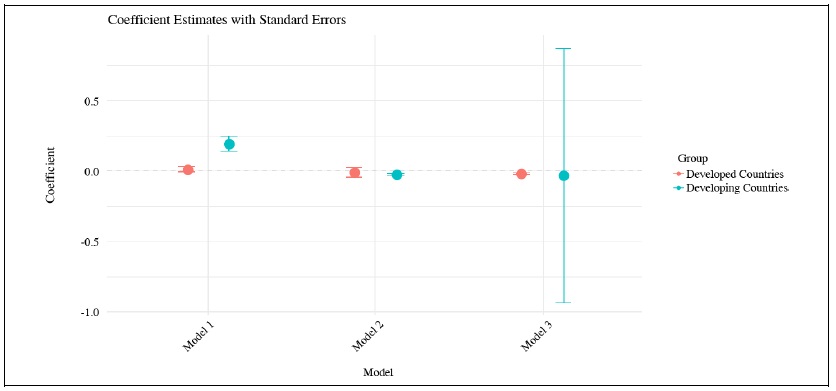

(3) Developed vs. developing

In Table 10 and Figure 5, we analyze developed and developing countries. Developed countries include Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and the United States, while developing countries include Brazil, Chile, China, India, Mexico, and Russia. Our results indicate that there is a massive difference in the impact of Political Risk (POLR), Geopolitical Risk (GPR), and Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) on developed and developing countries’ exports. Exports are positively affected by Political stability but relatively more so in developing countries. On the other hand, the impact is moderate in the case of developed countries. In contrast, developing countries seem to be more sensitive to political instability because of relatively weaker institutional frameworks and governance systems. Additionally, the vulnerability of developing economies to socio-political turmoil is intensified by their dependence on politically sensitive sectors (raw materials and agriculture).

Furthermore, it was found that the influence of geopolitical risk on the country’s trade performance is quite different for developed and developing countries. The developed countries seem not to be as much at risk from such threats because they have strong trade links and structures, substantial and diversified economic bases, and well-established infrastructure. Such aspects help them to cope with possible disruption associated with geopolitical concerns. However, developing countries are more sensitive to geopolitical risk, mainly arising from their concentrated trade, non-hedged trade profile, and limited capacity to deal with disruptions brought about by conflicts or sanctions. As a result, developing countries require efforts to improve trade diversification, improve economic stability, and strengthen infrastructure to deal with the risks that stem from geopolitical instabilities.

Developed and developing countries evidenced a significant negative export effect from Economic Policy Uncertainty, though such an effect was much more severe in developing economies. Policy uncertainty poses challenges for exporters, but in developed countries, these challenges are usually manageable as long as their economies and policy frameworks remain relatively stable. In developing countries, however, economic policy uncertainty can cause significant disturbances along the lines of currency volatility, inflation, and shifts in trade regulations, which can harm export performance. Developing economies are more sensitive to policy uncertainty because they rely on stable trade policies, foreign investment, and the conditions of external economies. Moreover, the confidence of investors and buyers is more easily undermined in developing economies, such that the adverse effects are also higher.

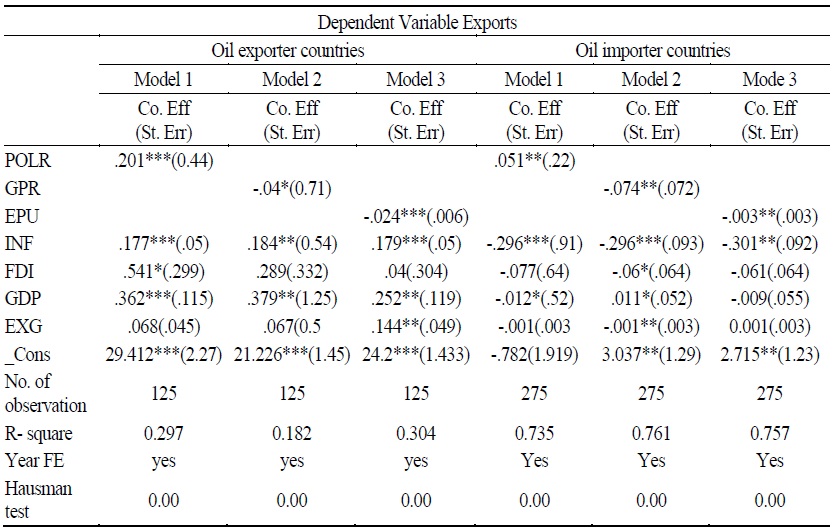

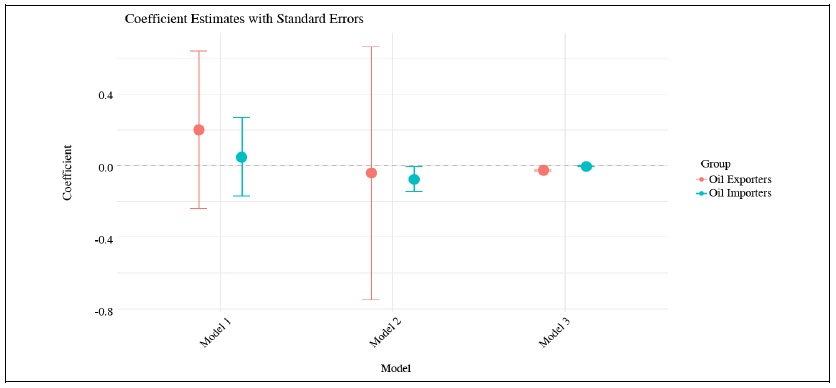

(4) Oil importing vs. exporting counties

Table 11 and Figure 6 analyzed Oil exporting and importing countries. Oil-importing countries include Australia, Germany, Chile, China, India, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and South Korea. Oil exporting countries include Canada, the United States, Brazil, Mexico, and Russia. Results found that political stability has a more substantial positive effect on exports in oil-exporting countries than in oil-importing countries. Hence, for Oil exporting nations, their economies are highly dependent on the output of Oil, and entrusting their resources to the hands of some strong leader for their uninterrupted business and their international trade, ensuring a stable political environment is essential. On the other hand, political stability is equally crucial for oil-importing countries. Still, the effect is not as significant, perhaps because their export compositions are less concentrated on a single primary resource such as Oil.

Exports are negatively affected by geopolitical risk, and the effect is more systematic for oil exporters than oil importers. That could, in part, reflect that oil-importing countries are more vulnerable to disruption in the global oil market due to geopolitical risk and its resulting impact on supply chain and trade flows. On the other hand, oil-exporting countries may also be affected positively by the same geopolitical risks. Increased oil prices associated with heightened risk partially offset the negative effect on trade volume. The research results from Pan et al. (2023) also showed that oil volatility is more strongly correlated with geopolitical risk in oil-importing countries than in oil-exporting countries.

EPU results show that exports decline most sharply in oil-exporting countries where economic policy uncertainty significantly reduces exports, especially relative to oil-importing countries. This shows how Oil exporting economies are sensitive to changes in policy environments, often having sizeable international trade and foreign investments in their oil sectors. However, oil-importing countries seem to respond weaker to economic policy uncertainty, perhaps due to the more diverse economic activities they conduct that offer them some resilience to policy-related risks.

V. Conclusion

Policy-related risk refers to shocks that affect a country’s trade and economy due to geopolitical risks, political instability, and uncertainty around economic policies. These risks pose significant risks to the global economic outlook and can impact companies, financial markets, and international trade. Geopolitical conflicts can harm trade and investment and affect currency exchange rates, government fiscal policies, and central bank monetary policies. Prior empirical research has conclusively demonstrated the significant impact of these risks on investment, trade, and other economic activities. However, little attention has been paid to the consequences of these actions on export policy. This study examines the combined effects and patterns of different hazards at national and regional levels by examining yearly data from 1998 to 2022 in 16 countries, building upon previous studies. It includes various dangers associated with policies, including uncertainty in economic policies, Geopolitical Risk, and political risk. This study used a fixed effect model, 2SLS, and 2-step GMM model to present the data.

We also check the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on our study model. Results show the negative effect of the economic crisis of 2008 on our model. Further, we divided the countries into the eastern and western regions, and the results show the same effect of policy-related risk on the export of goods and services but with different coefficients. Our analysis of oil-exporting and importing countries found that political stability has a more substantial positive effect on exports in oil-exporting countries than in importing countries. This is due to their dependence on oil output and the need for a stable political environment. Geopolitical risk negatively affects exports, making oil-exporting countries more vulnerable to global oil market disruptions. Oil volatility is more strongly correlated with geopolitical risk in oil-importing countries. Economic policy uncertainty significantly reduces exports in oil-exporting countries, indicating their sensitivity to policy changes.

Furthermore, developed countries have moderate impacts due to weaker institutional frameworks and governance systems. Geopolitical risk affects trade performance differently for developed and developing countries, with developed countries having stronger trade links and well-established infrastructure. Economic policy uncertainty significantly negatively affects exports, particularly in developing economies.

All our regression models (Fixed Effect, 2SLS, and GMM) show the same significant effect of policy-related risk on export goods and services with different significance levels and coefficients. Results reveal that POLR positively impacts exports because political stability fosters investor trust and promotes local and international investments in crucial areas, such as export-oriented businesses. Assuming political stability, the supply chain will be unaffected by abrupt governmental changes or social turmoil. Reliability is vital for organizations focused on exports, as timely delivery of goods is essential. The stability of political and economic conditions often leads to the stabilization of currency exchange rates. Businesses may effectively plan and carry out export activities without facing the potential cost swings caused by exchange rate volatility when exchange rates are stable. Countries with a stable political environment are more inclined to engage in negotiations and uphold advantageous trade deals.

The presence of stability enhances a country’s appeal as a business partner. Results of political risk show a negative impact on exports because it may be why Geopolitical conflicts frequently result in the implementation of trade obstacles, such as tariffs, quotas, and penalties, between nations. Geopolitical concerns lead to disturbances in worldwide supply systems. Conflicts or tensions may result in delays, heightened security threats, and elevated transportation expenses. Geopolitical risks can potentially erode economic stability in the places they impact, resulting in less economic activity and declining demand for imported goods. The decrease in demand directly affects exporters who focus on these markets. Increased geopolitical dangers are causing a decline in confidence among investors and consumers worldwide. The absence of trust resulted in decreased investment in industries focused on exporting. Our results of Economic policy uncertainty also show a negative impact on exports because Uncertainty in economic policy might cause enterprises to postpone or decrease their investments. Economic policy uncertainty encompasses concerns about the durability of trade agreements and the levels of tariffs. Export-oriented businesses depend on solid trade agreements to provide competitive access to international markets. Fluctuations in currency rates can be attributed to economic policy uncertainty.

Exporters prefer stable exchange rates as rate fluctuations complicate their ability to establish pricing, generate profits, and compete in international markets. Unpredictable economic policies can cause disruptions in global supply networks. Exporters depend on an intricate network of suppliers, and unpredictability may complicate operations and escalate expenses. Policymakers might employ focused tactics to lessen the impact of geopolitical concerns and unclear economic policies on exports. These include formulating long-term financial plans, implementing risk mitigation plans, assessing the effects of regulations, conducting regulatory impact analyses, stepping up diplomatic efforts, negotiating bilateral and multilateral agreements, providing insurance against geopolitical risk, and creating strategic stockpiles and alternate markets.

Policymakers can address geopolitical risks by bolstering diplomatic ties, negotiating trade agreements with provisions for mitigating political risk, providing geopolitical risk insurance, and promoting strategic stores of necessities or alternate markets. Creating strong information systems, encouraging innovation and diversification, and implementing crisis management frameworks are examples of general tactics. These tactics not only lessen the impact of geopolitical risks and unclear economic policies but also make export industries more resilient and competitive, guaranteeing steady export growth in the face of international political and economic difficulties.

The study has some limitations that could be covered in future research. Future research can examine the impact of policy-related risk on the export of goods and services separately. Additionally, it can explore the impact on imports in various trading sectors. In our study, we analyzed a sample of 16 leading economies. To enhance the robustness of future research, it is recommended that the sample size be expanded for more reliable results.

Tables & Figures

Table 1.

Data Discretion

Source: created by the author.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics

Source: calculated by the author.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix

Source: calculated by the author.

Table 4.

Diagnostic Test

Notes: This text outlines an analysis of diagnostic tests used to forecast the likelihood of heteroskedasticity. Four separate tests are performed to evaluate the existence of heteroskedasticity in the research model. The initial test refers to the decomposition method introduced by Cameron and Trivedi, widely known as the IM test. In addition, the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test is performed. In addition, the Modified Wald test is performed to assess the existence of heteroskedasticity. Ultimately, the Wooldridge test was utilized to detect the presence of heteroskedasticity.

Sources: calculated by the author.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic Test Results

Table 5.

Baseline Regression Analysis

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

Source: Calculated by the author based on data collected from 1998 to 2022.

Figure 2.

Baseline Regression Results

Table 6.

Fixed Effect and 2sls Regression Analysis

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

Source: calculated by the author.

Table 7.

GMM (two-step) Regression Analysis

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

Source: calculated by the author.

Figure 3.

Fixed Effect, 2sls and GMM Regression Results

Table 8.

Financial Crisis 2008 Impact

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

Source: calculated by the author.

Table 9.

Regional Analysis of Regional Effect

Source: calculated by the author.

Figure 4.

Regional Effect

Table 10.

Fixed Effect Analysis of Developed and Developing Countries

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1 above table shows the results of fixed-effect regression. Model 1 indicates the impact of Political stability on export, model 2 indicates the Geopolitical risk and export, and Model 3 shows the results of Economic policy uncertainty and export.

Source: calculated by the author.

Figure 5.

Developed vs. Developing Countries Effect

Table 11.

Fixed Effect Analysis of Oil Exporting and Importing Countries

Notes: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1 above table shows the results of fixed-effect regression. Model 1 indicates the impact of Political stability on export; model 2 indicates the Geopolitical risk and export, and model 3 shows the results of Economic policy uncertainty and export.

Source: calculated by the author.

Figure 6.

Oil Exporting vs. Importing Countries Results

References

-

Aisen, A. and F. J. Veiga. 2013. “How does political instability affect economic growth?”

European Journal of Political Economy , vol. 29, pp. 151-167.

-

Anser, M. K., Yousaf, Z., Nassani, A. A., Alotaibi, S. M., Kabbani, A., and K. Zaman. 2020. “Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: two-step GMM estimates.”

Journal of Economic Structures , vol. 9, pp. 1-25.

-

Aralica, Z., Svilokos, T., and K. Bacic. 2018. “Institutions and firms’ performance in transition countries: the case of selected CESEE countries.”

South East European Journal of Economics and Business , vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 68-80.

-

Azzimonti, M. and M. Talbert. 2014. “Polarized business cycles.”

Journal of Monetary Economics , vol. 67, pp. 47-61.

-

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., and S. J. Davis. 2016. “Measuring economic policy uncertainty.”

The Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 131, no. 4, pp. 1593-1636.

-

Balcilar, M., Bonato, M., Demirer, R., and R. Gupta. 2018. “Geopolitical risks and stock market dynamics of the BRICS.”

Economic Systems , vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 295-306.

-

Basu, S. and Bundick, B. 2017. “Uncertainty shocks in a model of effective demand.”

Econometrica , vol. 85, no. 3, pp. 937-958.

-

Bloom, N. 2009. “The impact of uncertainty shocks.”

Econometrica , vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 623-685.

-

Born, B. and J. Pfeifer. 2014. “Risk matters: The real effects of volatility shocks: Comment.”

American Economic Review , vol. 104, no. 12, pp. 4231-4239.

-

Caldara, D. and M. Iacoviello. 2022a. “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.”

American Economic Review , vol. 112, no. 4.https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20191823

-

Caldara, D. and M. Iacoviello. 2022b. “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.”

International Finance Discussion Papers 1222r1. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.https:// doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2022.1222r1 -

Caldara, D., Iacoviello, M., and A. Markiewitz. 2018. “Country-specific geopolitical risk.”

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board . - Carballo, J., Handley, K., and N. Limão. 2018. “Economic and policy uncertainty: Export dynamics and the value of agreements.” Working Paper, no. 24368. National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

Chiu, Y.-B. and Lee, C.-C. 2019. “Financial development, income inequality, and country risk.”

Journal of International Money and Finance , vol. 93, pp. 1-18.

-

Choi, B. and J. S. Oh. 2022. “Rise of Geopolitics and Changing Korea and Japan Trade Politics.”

East Asian Economic Review , vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 27-48.

-

Darby, J. L., Ketchen Jr, D. J., Williams, B. D., and T. Tokar. 2020. “The implications of firm‐specific policy risk, policy uncertainty, and industry factors for inventory: A resource dependence perspective.”

Journal of Supply Chain Management , vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 3-24.

-

Dong, G., Kokko, A. and H. Zhou. 2022. “Innovation and export performance of emerging market enterprises: The roles of state and foreign ownership in China.”

International Business Review , vol. 31(6), no. 102025.

-

Engel, C. 2014. “Chapter 8. Exchange rates and interest parity.”

Handbook of International Economics , vol. 4, pp. 453-522. -

Fosu, A. K. 2003. “Political instability and export performance in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Journal of Development Studies , vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 68-83.

-

Fredriksson, P. G. and J. Svensson. 2003. “Political instability, corruption and policy formation: the case of environmental policy.”

Journal of Public Economics , vol. 87, no. 7-8, pp. 1383-1405.

-

Glick, R. and A. M. Taylor. 2010. “Collateral damage: Trade disruption and the economic impact of war.”

The Review of Economics and Statistics , vol. 92, no. 1, pp.102-127.

-

Góes, C. and E. Bekkers. 2022. “The impact of geopolitical conflicts on trade, growth, and innovation.”

ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2203.12173 . -

Greenland, A., Ion, M., and J. Lopresti. 2019. “Exports, investment and policy uncertainty.”

Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique , vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 1248-1288.

-

Gulen, H. and M. Ion. 2016. “Policy uncertainty and corporate investment.”

The Review of Financial Studies , vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 523-564. -

Gupta, R., Gozgor, G., Kaya, H., and E. Demir. 2019. “Effects of geopolitical risks on trade flows: Evidence from the gravity model.”

Eurasian Economic Review , vol. 9, pp. 515-530.

-

Gurgul, H. and Ł. Lach. 2013. “Political instability and economic growth: Evidence from two decades of transition in CEE.”

Communist and Post-Communist Studies , vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 189-202.

-

Hosny, A. 2017. “Political stability, firm characteristics and performance: Evidence from 6,083 private firms in the Middle East.”

Review of Middle East Economics and Finance , vol. 13(1), no. 1.

-

Hu, G. and S. Liu. 2021. “Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) and China’s Export Fluctuation in the Post-pandemic Era: An Empirical Analysis based on the TVP-SV-VAR Model.”

Frontiers in Public Health , vol. 9, pp. 1-11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.788171 -

Huang, N. and P. Guo. 2015. “The impact of economic policy uncertainty on macroeconomy and its regional difference—evidence from China with the panel VAR Model.”

Financ Econ , vol. 6, pp. 61-70. -

Jin, H. and Y. Shin. 2022. “Global Geopolitical Risk and International Trade of Korea: Do Politics Matter?”

SSRN Electronic Journal .https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4057393 -

Kamara, A. and N. P. Koirala. 2023. “The dynamic impacts of monetary policy uncertainty shocks.”

Economies , vol. 11(1), no. 17.

- Khalil, C., Mirza, D., and C. Zaki. 2020. “The Impact of Political Instability on Egypt’s Exports: Evidence from Firm-Level and Geo-Localized Data.” Egyptian Center for Economic Studies. Working Paper, no. 206.

-

Khan, K., Su, C. W., and S. K. A. Rizvi. 2022. “Guns and Blood: A Review of Geopolitical Risk and Defence Expenditures.”

Defence and Peace Economics , vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 42-58.https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2020.1802836

-

Kim, C. Y. and H. Jin. 2023. “Does geopolitical risk affect bilateral trade? Evidence from South Korea.”

Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy , vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1834-1853.https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13547860.2023.2204693

-

Le, Q. V. and P. J. Zak. 2006. “Political risk and capital flight.”

Journal of International Money and Finance , vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 308-329.

-

Leduc, S. and Z. Liu. 2016. “Uncertainty shocks are aggregate demand shocks.”

Journal of Monetary Economics , vol. 82, pp. 20-35.

-

Lee, C.-C. and C.-C. Lee. 2018. “The impact of country risk on income inequality: A multilevel analysis.”

Social Indicators Research , vol. 136, pp. 139-162.

-

Lee, C. C., Lee, C. C., and S. Xiao. 2021. “Policy-related risk and corporate financing behavior: Evidence from China’s listed companies.”

Economic Modelling , vol. 94 (November 2019), pp. 539-547.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.01.022

-

Liu, G. and Zhang, C. 2020. “Economic policy uncertainty and firms’ investment and financing decisions in China.”

China Economic Review , vol. 63, no. 101279.

-

Matta, S., Appleton, S., and M. Bleaney. 2018. “The microeconomic impact of political instability: Firm‐level evidence from Tunisia.”

Review of Development Economics , vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 1590-1619.

-

Mueller, P., Tahbaz‐Salehi, A., and A. Vedolin. 2017. “Exchange rates and monetary policy uncertainty.”

The Journal of Finance , vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 1213-1252.

-

Murad, M. S. A., and N. Alshyab. 2019. “Political instability and its impact on economic growth: the case of Jordan.”

International Journal of Development Issues , vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 366-380.

-

Nagheli, S. and M. Maddah. 2017. “The Effect of Political Institutions on Iranian Export to Major Trading Partners in Different Commodities Groups.”

Quarterly Journal of Applied Theories of Economics , vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 59-90. -

Olney, W. W. 2016. “Impact of corruption on firm‐level export decisions.”

Economic Inquiry , vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 1105-1127.

-

Pan, Z., Huang, X., Liu, L., and J. Huang. 2023. “Geopolitical uncertainty and crude oil volatility: Evidence from oil-importing and oil-exporting countries.”

Finance Research Letters , vol. 52, no. 103565.

-

Pollins, B. M. 1989. “Conflict, cooperation, and commerce: The effect of international political interactions on bilateral trade flows.”

American Journal of Political Science , vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 737-761.

-

Qadri, N., Shah, N., and M.N. Qureshi. 2020. “Impact of political instability on international investment and trade in Pakistan.”

European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 283-305. -

Shabir, M., Jiang, P., Bakhsh, S., and Z. Zhao. 2021. “Economic policy uncertainty and bank stability: Threshold effect of institutional quality and competition.”

Pacific-Basin Finance Journal , vol. 68, no. 101610.

-

Sharma, C. and R. Khanna. 2024. “Risk, Uncertainty and Exporting: Evidence from a Developing Economy.”

Journal of Quantitative Economics , vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 151-177.

-

Shi, S., Sun, Q., Xi, Z., Hou, M. and J. Guo. 2022. “The impact of country risks on the dependence patterns of international cobalt trade: a network analysis method.”

Frontiers in Energy Research , vol. 10, no. 951235.

-

Soybilgen, B., Kaya, H., and D. Dedeoglu. 2019. “Evaluating the effect of geopolitical risks on the growth rates of emerging countries.”

Economics Bulletin , vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 717-725. -

Tabassam, A. H., Hashmi, S. H., and F. U. Rehman. 2016. “Nexus between political instability and economic growth in Pakistan.”

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , vol. 230, pp. 325-334.

-

Talamanov, P. 2024. “Research on the Impact of Geopolitical Instability on Russian Trade.”

International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation , vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1276-1297.

-

Tang, R. W. and P. J. Buckley. 2020. “Host country risk and foreign ownership strategy: Meta-analysis and theory on the moderating role of home country institutions.”

International Business Review , vol. 29(4), no. 101666.

-

Wang, Z., Zong, Y., Dan, Y., and S.-J. Jiang. 2021. “Country risk and international trade: evidence from the China-B&R countries.”

Applied Economics Letters , vol. 28, no. 20, pp. 1784-1788.

-

Xiaofen, T., Kai, Z., and G. Yaying. 2018. “The impact of global economic policy uncertainty on capital flows in emerging economies.”

Finance and Trade Economics , vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 35-49. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-8102.2018.03.003. - Yang M, G. X. 2018. “The impact of economic policy uncertainty on the effectiveness of monetary policy.” Paper presented at Statistics and Information Forum, 33:54-61. (in Chinese) 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3116.2018.07.007.

-

Zhang, L. and S. Hu. 2023. “Foreign uncertainty and domestic exporter dynamics.”

International Review of Financial Analysis , vol. 87, no. 102629.

-

Zhou, H., Fan, J., Yang, X., and K. Duan. 2023. Food export stability, political ties, and land resources.

Land , vol. 12(10), no. 1824.