- EAER>

- Journal Archive>

- Contents>

- articleView

Contents

Article View

East Asian Economic Review Vol. 27, No. 1, 2023. pp. 61-85.

DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2023.27.1.418

Number of citation : 2Do Women's Attitudes Matter in Acceptance of Islamic Microfinance? Evidence from Malaysia

|

Multimedia University |

|

|

Multimedia University |

|

|

Multimedia University |

|

|

Northern University Bangladesh |

|

|

Sakarya University |

Abstract

The study aims to investigate the factors pursuing the women entrepreneurs to accept Islamic microfinance (IMF) in urban and rural areas of Malaysia. For this purpose, the study applies the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Innovation and Diffusion Theory to explain Islamic microfinance adoption. Using the structural equation model (SEM) with primary data collected from 384-woman entrepreneurs in Malaysia, the current study uses a 5-point Likert scale. On the basis of theory and collected data, the seven hypotheses are developed. All hypotheses are validated by both directly and indirectly, as well as through a mediating factor. Among the factors, knowledge about IMF and subjective norms significantly influence the acceptance of IMF. On the other hand, the perceived complexity does not show any substantial relationship to the acceptance of IMF. This outcome will be helpful in supporting policymakers, academics, and future studies and must take into account the supported factors. Therefore, the study contributes to develop an innovative framework, to create self-employment for women entrepreneurs.

JEL classification: B26, G10, G21, L26

Keywords

Women, Entrepreneurs, Microfinance, Malaysia, Islam

I. Introduction

1. Islamic Microfinance

Islamic microfinance (IMF) offers such a system that pursue entrepreneurs to accept risk-sharing in financial activities. Its development policy that supports the vulnerable to reduce poverty is based on Islamic principles, referring to interest-free financial activities. In this system, the moral and ethical values of Islamic man are taking place in the center, and their religious ethics is considered a safeguard in the performance of Islamic microfinance (Muchnick and Kollamparambil, 2015). According to the Islamic financial system, Islamic microfinance is an interest-free loan to small entrepreneurs among the low-income groups. As an instrument, it contributes to enhancing the living standard of deprived people and reducing the inequality within the society that derives the economic development and solution for many economic problems.

Moreover, Islamic microfinance aims to create human capital that generates social wealth for balanced economic growth, apparently similar to conventional microfinance. However, the notion of social and human capital is far distinct since the prime objective of Islamic Shariah is to ensure brotherhood and cohesion within the society, freedom of expression, and information acquisition. By applying the Shariah, Islamic microfinance intends to postpone the vicious cycle of poverty and offers a new development path that gets the poor out of poverty.

In addition, Ashrafi (2017) pointed out that in most cases, traditional microfinance did not reduce the poverty cycle. And the poor people were caught in the trap of traditional microfinance, which followed a spiral of indebtedness, particularly for the hardcore poor people. Instead of microfinance, Shari’ah based instruments, like Qard Hasana (cost and interest free loan) and participatory commercial microfinance (Musharaka, Mudaraba, Ijara, ets.) could make the cycle of poverty and burden of indebtedness. In order to effectively alleviate poverty, many studies have recommended using an inclusive and comprehensive strategy that combines charitable and commercial funding to help both the idle poor and the destitute (Obaidullah, 2008; Hassan et al., 2013; Shirazi, 2014).

The women are still lagging behind than their counterparts. Generally, the women invest their earnings to individual and family affairs (Samer et al., 2015). However, the woman entrepreneurs are trusted microcredit borrowers, and play a pivotal role to economic development (Md Isa et al., 2018), especially in Malaysia. It motivates to investigate factors influencing the women to receive the Islamic microcredit.

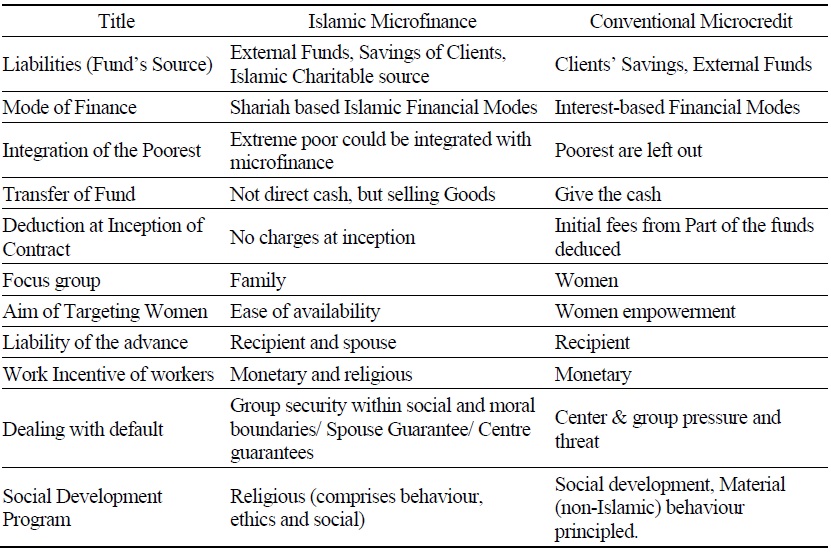

2. The Distinction between Conventional Microcredit & Islamic Microfinance

According to Baber (2019), Islamic banking encompasses not just interest-free banking (referred to as riba), but also the integration of ethics and money as a paradigm for serving and leading for an equal and better society. Islamic microfinance adheres strictly to Islamic Shariah rules and does not impose interest, whereas conventional microfinance adheres to the standard financial system and imposes financial interest. Thus, there are several critical distinctions between conventional and Islamic microfinance (Abdelkader and Salem, 2013). These products are oriented on commercial partnerships and profit-sharing (mudhorobah), which are critical components of establishing sharia-compliant financial institutions (Muhammad, 2020).

II. Literature Review

Several studies have found that Islamic Microfinance effectively faced financial challenges and contributed to alleviating the poverty level instead of conventional microfinance (Ahmad et al., 2020; Hussein Kakembo et al., 2021; Parvej et al., 2020). Islamic microfinance, with adaption to the ethical and participatory schemes- qardhul hasan, murabahah, and ijarah, has the great potential to alleviate poverty (Rahman, 2010). It can achieve social and economic levels of diminished poverty (Rokhim et al., 2016). It is an essential tool for poverty reduction, according to Schmidt (2015). Moreover, microfinance is introduced to provide the support for the small and medium enterprises and micro-entrepreneurs in a situation where they do not have any access to get the banking services due to high operating cost and less collateral and is generally applied to micro entrepreneurs, those have difficulties in reaching finance and insurance-related services due to economic resources limitations (Ameer, 2013). Therefore, microcredit shows the strength to develop the financial sources available to the bottom class of the community, particularly women, creating an opportunity for them to make better living standards (Hameed et al., 2020).

Islamic microfinance contributes to alleviating poverty and especially play a dominant role in empowering women. In this regard, the access of Islamic microfinance for women is an important pillar for social integration. Umar et al. (2021) concluded that subjective norms, perceived behavior, and attitude as factors of the Theory of Planned Behaviour directly influenced on Islamic microfinance. Conversely, the negative nexus between financial conditions and Islamic microfinance among agribusiness customers was concluded in the same study. Another research, using the self-administered 239 questionnaires in Tunis City, found the factors that are religious commitment, knowledge regarding Islamic finance and relative advantage of Islamic banking, and compatibility with customer ethics contributing to predicting the adoption of Islamic banking (Obeid and Kaabachi, 2016). Hence, in our research, we will investigate whether factors of the TPB & IDT have any direct or indirect effect on the acceptance of Islamic microfinance by women entrepreneurs.

The factors such as relative advantage, knowledge regarding Islamic microfinance, subjective norms through social system norm as a mediating factor motivated women’s intention to use Islamic microfinance. The behavioral norms contribute to developing the modern-day economy by reducing poverty and unemployment and empowering women (Islam et al., 2021). In this regard, the theory of planned behavior by scholar Ajzen (2005) analyzed the causes why an Islamic man embraces the Islamic microfinance programs. According to the theory’s explanation, one of the crucial factors of real behavior is the intention of a person. The theory of Planned Behaviour defines intention as a cognitive illustration of a person’s actions. Among other internal and external factors like religion, experience, the views and perspectives of close ones, social position, and economic solvency, personal norms that possibly shape individual behavior are considered as dominant factors (Mansori et al., 2020).

In general, by affirming or at least a reasonable attitude of society toward a given activity, an individual may be persuaded to have a more positive or supporting intention to carry out the certain action. For example, Muslims’ intentions in microfinance programs are intimately tied to their behavioral beliefs and attitudes regarding the product (Ajzen, 2005). Suppose an individual believes in the law of Islamic Shariah that is compatible with a banking procedure. In that case, he may feel more optimistic about applying for Islamic microfinance-related services and goods.

Islamic microfinance, according to Hartarska et al. (2013), is a financial advantage offered to lower-income groups and entrepreneurs looking to launch a small or medium business. In Malaysia, Islamic microfinance has positively impacted earnings, standard education system, resources for financial access, women empowerment, poverty reduction, and improved health benefits. The significant findings in the study of Badri (2013) suggest that women’s participation in microfinance programs contributes to women’s empowerment, particularly regarding the sociocultural and economic aspects of empowerment. According to the outcomes, the project has aided in providing education, better-off, uses of utility, craft services, and fuel. Microfinance providers (MFPs), according to Siddig (2013), have significantly contributed to providing financial services for the disadvantaged and their businesses. According to the research of Elmola and Belal (2013), microcredit has a 16 percent beneficial influence on poverty reduction.

In contrast, providing financial means to the poor in the traditional microfinance system may be costly, inefficient, and undesirable for multi-functional goods, which is considered the major difficulty with vulnerable group’s entrance to finance (Pareek and Raman, 2016). The disparity among financial institutions is sometimes attributed to high-level operating expenses (Ibrahim and Bauer, 2013). Furthermore, Ammar and Ahmed (2016) pointed out that geographic remoteness is a key barrier to disadvantaged individuals using traditional banking services. According to the report, banks can only aggressively target the vulnerable if they identify the potential to financially serve these clients (Agwu and Carter, 2014).

Malaysia’s microfinance policy efforts have achieved moderate and significant progress toward their goals. By applying Microfinance, Malaysia has also shown an effective means of establishing business activity to alleviate poverty. According to Yousif et al. (2013), microfinance organizations now confront two major challenges: inefficiency in organizational structure and high operational expenses, both of which lead to high-interest rates. The IDT is defined as “innovations offering benefits, perceived compatibility with existing practices and beliefs and low complexity, possible trialability and observability will have a more generalized and rapid rate of spreading.” Accepting the implementation of Islamic microfinance is thus a positive behavioral aim. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), planned behavior theory (PBT) evaluates the influence of determination to accomplish in anticipate that the organization is capable of adopting the corporate sustainability policy (Ajzen, 1991). The mental and neural condition of the business stakeholders, which influences the implementation of a circular economy in the goods and operations of organizations, is characterized by attitude (Kumar et al., 2012). Therefore, the study framework was created using TPB and IDT, as presented in the methodology section.

III. Methodology of Research

1. Hypotheses Formulation with Theoretical Background

A theoretical perspective is a quantitative reflection representing how a study formulates a reasonable understanding of the links among various factors which are critical to the problem (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). Experimented theories are usually developed after the theoretical structure has been developed to see if the suggested assumption is justified based on the study findings.

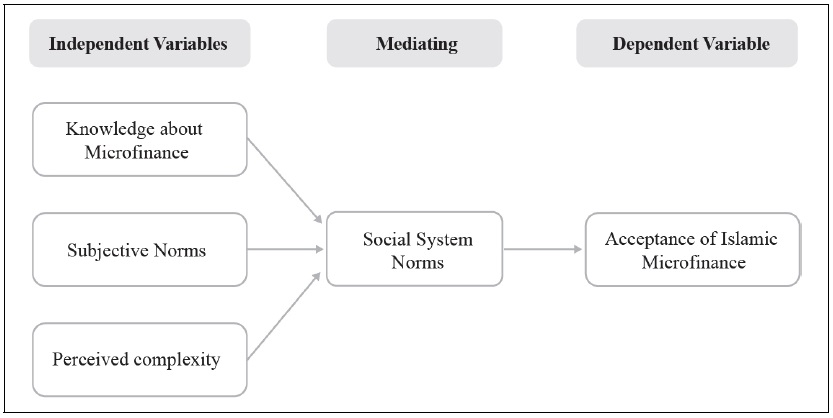

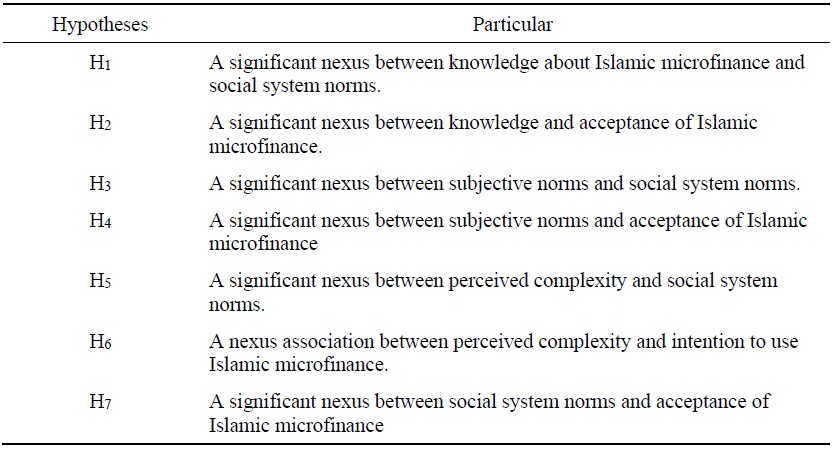

Accordingly, the current study has focused on innovation, adoption, marketing services, and customer behavior since this research aims to examine women entrepreneurs’ participation in Islamic microfinance and its impacts on Malaysian society. It has taken to develop its structure by using the Planned Behaviour Theory (TPB) and Invention Diffusion Theory (IDT), which are now widely used in various innovation recognized studies. Ultimately, the research structure was created using IDT and TPB (Invention Diffusion Theory and Planned Behaviour Theory) (See Figure 1).

2. Variables Definition and Development of Hypothesis

(1) Knowledge regarding microfinance

Knowledge is the outcome of originating facts based on an individual’s dexterity and is affected by his/her behavior (Brimah et al., 2020). Moreover, Sveiby (2001) expanded by illustrating it as a “process of knowing” and an activity. The information is prepared in the brain (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). On the other hand, knowledge is defined as inculcating through insight, logic, opinion, understanding, or several other types of education (McInerney, 2002). In addition, understanding is defined by Kivumbi (2011) as knowledge of facts gained via research, interpretation, or personal observations. Thus, the present study looks at women entrepreneurs’ understanding of IMF projects as a motivating force, while a gap in the information on IMF schemes is seen as a barrier. Therefore, in the research, microfinance practice is investigated as a motivating factor for IMF involvement, whereas limited access to credit amenities is considered a barrier. The following assumptions are then investigated:

Ha1: A significant nexus between knowledge and social system norms.

Ha2: A significant nexus between knowledge and acceptance of Islamic microfinance.

(2) Subjective norms

Subjective norms are people’s assumptions or judgments about others’ intentions and whether or not people will follow those actions (Huda et al., 2012). It is referred to as this dimension since this interpretation is subjective in nature. On the other hand, beliefs influence attitudes toward conduct and subjective standards in a similar way (Huda et al., 2012). Subjective norms are an outcome of social values that are formed by others (Hanno and Violette, 1996; Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Huda et al., 2012). As a result, it is hypothesized that:

Hb1: A significant nexus between subjective norms and social system norms.

Hb2: A significant nexus between subjective norms and acceptance of Islamic microfinance

(3) Perceived complexity

Perceived complexity is linked to thinking about complexity. The researchers defined complexity has been understood as the output resulting from a specific perception of a condition made by a viewer, which can be designated as ‘perceived complexity’. These are based on the premise that, while not being the same, the subject and object are not radically different. A complete (total) distinction would make it difficult to know. As it has been said, uncertainty lies as much in the beholder’s eye as in the configuration and actions of a process it.

Hc1: A significant nexus between perceived complexity and social system norms.

Hc2: A nexus association between perceived complexity and intention to use Islamic microfinance.

(4) Norms of social system

Social system norms are an approach to pursuing behavior based on social standards. A repeatedly doing actions or behavior in a particular group, for example, a group of people writing reviews, is referred to as a social norm (Burtch et al., 2018). This kind of social norm is a descriptive social norm (Cialdini et al., 1991).

In a variety of situations, social norms are considered to be beneficial, including stimulating voter participation (Gerber and Rogers, 2009), inspiring the repeated use of financial products (Goldstein et al., 2008), decreasing energy usage (Allcott, 2011; Nolan et al., 2008; Schultz et al., 2007), diminishing water use (Ferraro and Price, 2013), and expanding the consumption of nutritious foods (Ferraro and Price, 2013; Robinson et al., 2014). As a result, the following theory has been put forward:

Hd1: A significant nexus between social system norms and acceptance of Islamic microfinance

(5) Acceptance of Islamic microfinance

The studies on microfinance, basically, focus on how microcredit can have an impact on people, loan repayment patterns, and savings practices that may curb the expansion of microfinance. Many research has affirmed that microfinance contributed to enhancing consumers’ living standard and their facilities. (Girabi and Mwakaje, 2013). However, behavioral factors were ignored in many previous studies. For many factors such as high-interest rates and lack of knowledge, perceived complexity deter the women entrepreneurs in Malaysia from accepting the Islamic microfinance. Umar et al. (2021) confirmed that subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control directly contribute to accepting Islamic microfinance. On the other hand, with these variables, relative advantage and religious commitment are dominant factors in predicting the adoption of Islamic banking (Obeid and Kaabachi, 2016).

Dahir (2015), Ahlén (2012), and Morduch and Haley (2002) all acknowledged microfinance’s favorable impact on enhancing households’ ability to satisfy consumer demands, increase investments, enhance living standards, and reduce vulnerability. The recognition of behavioral factors that promote individual acceptance of Islamic microfinance presents insightful guidelines for policymakers and practitioners, who intend to encourage microfinance use to improve their advantages.

(6) Estimation and result

In the research, survey-based methodologies are used. The women entrepreneurs are classified by industry, and then the sample is chosen using essential random selection (SRS). The instrument’s final edition included several incentives and barriers for women entrepreneurs. They generally manage small enterprises to participate in Islamic microfinance.

Multiple procedures are employed to compute all factors, each with a corresponding anchor on a Likert Scale ranging from 1 to 5, with notion one as “Strongly Disagree” and five as “Strongly Agree.” The participants were asked to select one of five options for each item included. Micro women entrepreneurs in Malaysia’s urban and rural areas were given 415 questionnaires, of which 400 were sent back. However, only 384 were deemed appropriate for the research.

By using frequencies and percentages, the descriptive statistics analyzed the data. For this analysis, the SPSS-23 and SmartPLS-3.0 have been used.

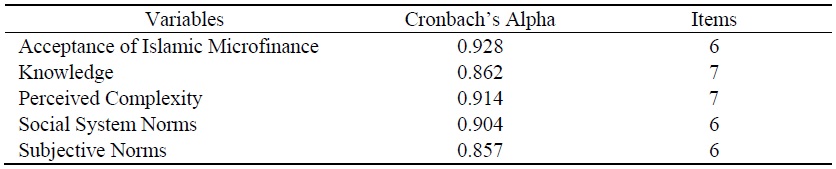

The data’s internal consistency was initially checked by SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) to examine it. The Cronbach’s alpha for microfinance customer variables is shown in the following table. A value greater than 0.70 for microfinance consumers indicates that data reliability is sufficient.

IV. Result and Discussion

1. Respondent Demographic Profiles

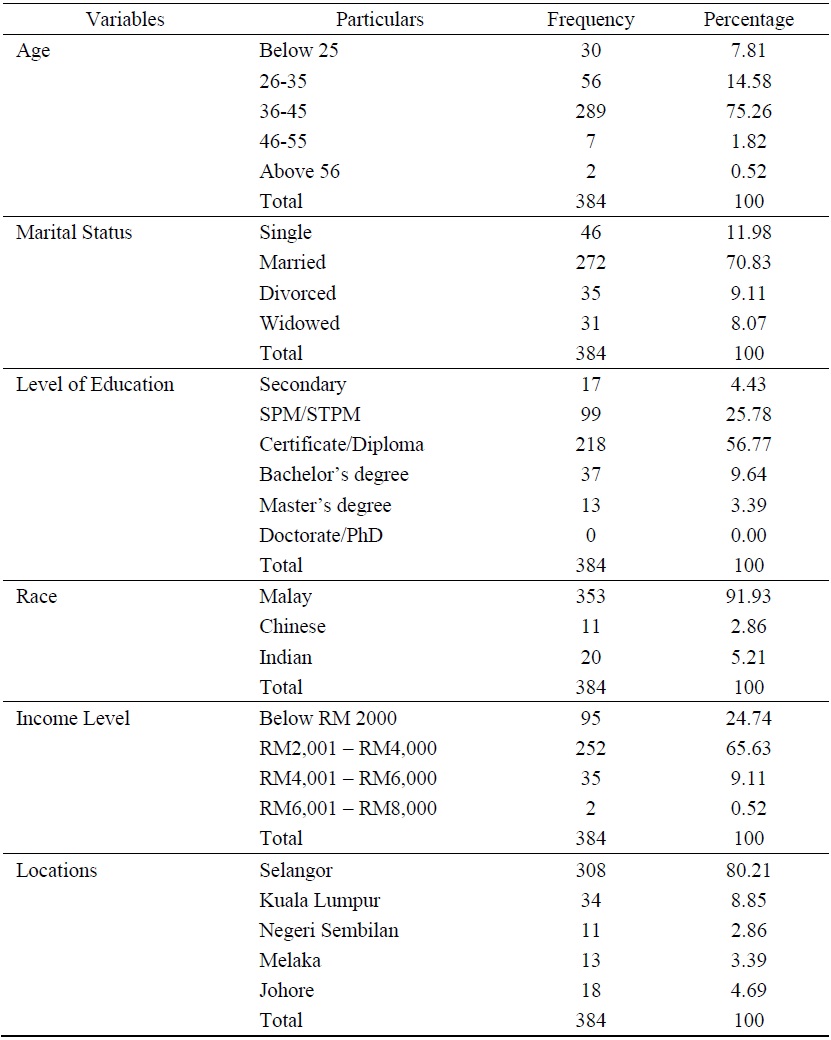

In this study, all respondents were women entrepreneurs. The age categories are dominated by the 36-45 years, who account for 75.3 percent of the total, followed by the group of 26-35 years, who account for 14.6 percent. The majority of the respondents are married, with 126 respondents (72.5%), while the remaining 11.8 percent are single. Most of the participants (56.75 percent) have a certificate or diploma, followed by SPM/STPM (25.85%) and a bachelor’s degree, which is 9.55%. Malay Muslims receive the most responses (92.10%), followed by Indians. Most of the respondents (65.75 percent) earn between RM2,001 and RM4,000 per month, with 24.72 percent earning less than RM2000. The research was based on five Malaysian states. Selangor has the highest percentage of responders (80.35%), followed by Kuala Lumpur (9%).

2. Measurement Model Assessment

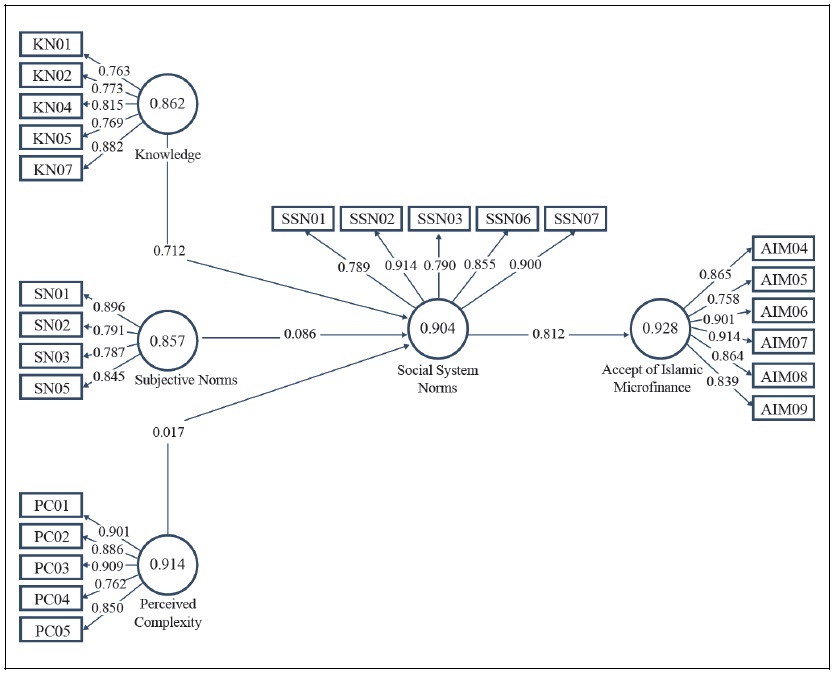

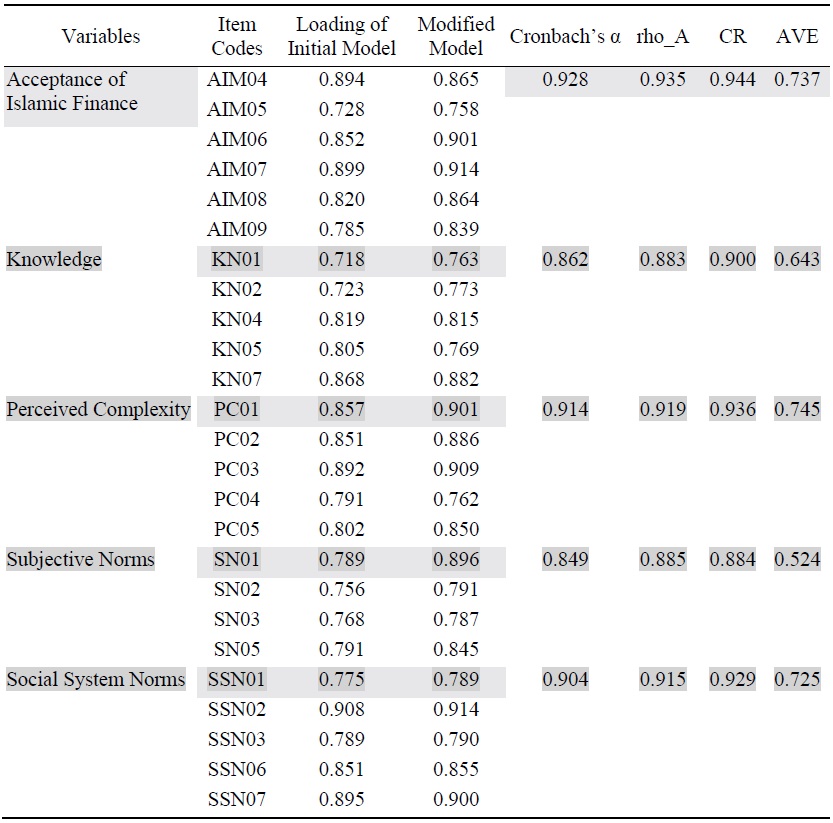

Here are five factors (contracts) that are assessed by using a measurement model, and their indicators are used to see how the latent construct is weighted using the practiced indicators. For this reason, the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability, factor loading, and discriminant validity were investigated. This was accomplished using SmartPLS-3.0. It is beneficial to discover instrument flaws (Cooper and Schindler, 2001) factor loading in the instrument is depicted in Figure 2.

(1) Reliability of indicator

According to the validity criterion, indicator consistency is good when each item’s loading is at least 0.7, and this is significant at the 0.05 level. Ramayah et al. (2018) argued that if the overall AVE is at least 0.5, any item with a loading lower than 0.7 is acceptable. Moreover, the value of AVE should be at least 0.5 to determine convergence (Hair et al., 2010). In the study, the AVE for all microfinance consumer variables contains values that are larger than 0.5, referring to the good convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). In exploratory research, the composite reliability values are accepted between 0.60 to 0.70, while in the more advanced stage, the value must be greater than 0.70 (Ab Hamid et al., 2017). As seen in Table 3, all constructs in our study exceeded this criterion. Table 4 also shows that factor loading is more significant than 0.7 for each item, composite reliability is greater than 0.7, and the AVE is greater than 0.7. As a result, all numbers are outside the permitted range. A value of rho above 0.8 indicates good internal consistency, while 0.7 represents the lower limit of adequacy (Cicchetti, 1994) where the Table 4 also shows that factor loading is more significant than 0.7 for each item, composite reliability is greater than 0.7.

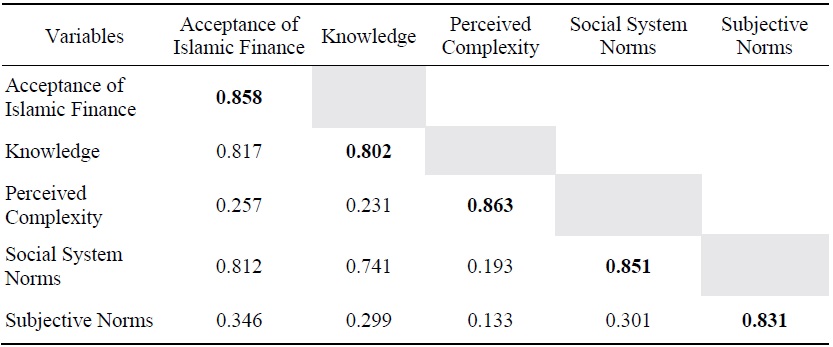

(2) Validity of discriminant

The construction of validity discriminant reflects more variance with its given variables than any other construct, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981), which refers to the square root of AVE higher than the construct of other correlation. The AVE is the mean variation in a construct’s indicator variables expressed as a percentage of indicators’ total variance. With the significant diagonals equaling the square root of the AVE, Table 5 presents the construct’s correlation matrix.

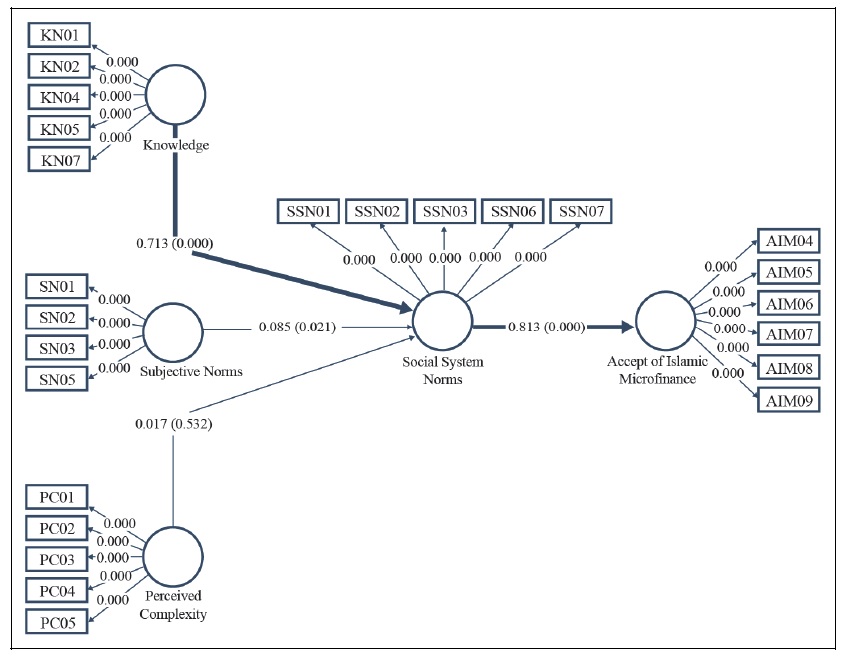

3. Structural Model Assessment

A structural model is a criterion that is used for hypothesis checking (Hameed et al., 2018; Hameed and Naveed, 2019). A measurement model takes into consideration latent variables or composite variables (Hoyle, 1995, 2011; Kline, 2010), whereas a structural model tests all possible dependencies using path analysis. (Hoyle, 1995, 2011; Kline, 2010). The following figure illustrates the structural model assessment for all of the factors and their items.

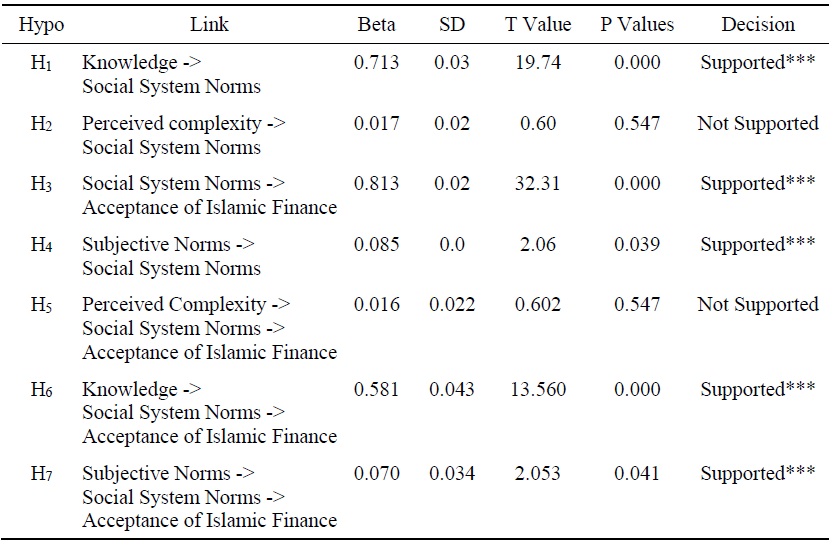

(1) Testing of hypothesis

In the following table, the p-value, if less than 0.05, shows the significant relationship between variables. Here, all factors except perceived complexity belong to p-values less than 0.5, which means a significant relationship. In addition, the positive beta value indicates that the independent variables have a significant relationship with the dependent variables. In this regard, the perceived complexity shows the p-value greater than 0.05, referring to the insignificant relationship with social system norms and acceptance of Islamic microfinance. However, all other-five hypotheses hold a significant nexus, such as, the knowledge about Islamic microfinance has a significant positive influence on social system norms. Wahyudi (2015) concluded the same kind of study. In addition, the social system norms has a pivotal role on the adoption of Islamic Microfinance, affirmed by the study of Purwanto et al. (2022). The subjective norms through moderating channel affect in the acceptance of Islamic microfinance and also directly affect social system norms (Bananuka et al., 2019).

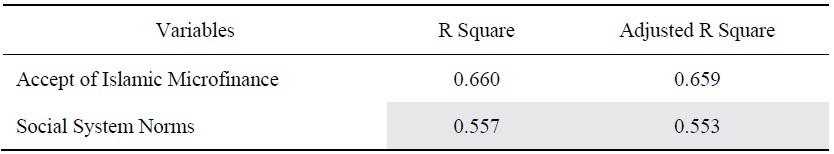

(2) R-squared & F-squared

The value of R-squared refers to the variations in regressand that is explained by regressors. The higher value of R-squared, the more fitted model. The value of R-squared 0.60, 0.33, and 0.19 show substantial, moderate, and weak values consecutively (Chin, 1998). Table 6 demonstrates the value of R-Square, which explains 0.66 and 0.659 of variance in micro-enterprise success. According to Chin (1998), this value is substantial. In addition, Hair et al. (2011, 2013) recommended the rule of thumb for R-squared values i.e., 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25, which referred to substantial, moderate, and weak consecutively for endogenous latent variable.

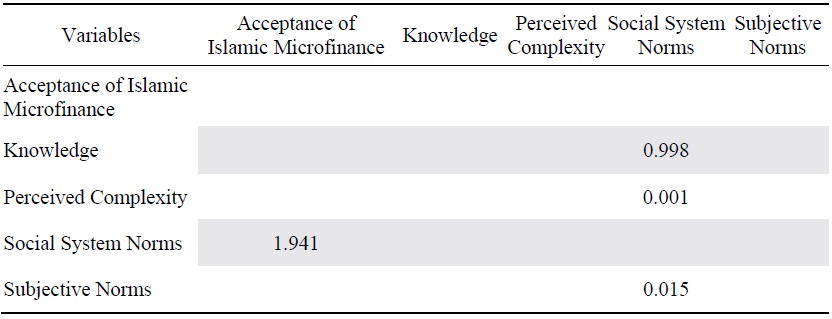

F-square means the variation in r-Square while removing exogenous variables from the model. Cohen (2013) defined the f-squared effect size: 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 as small, medium, and large sequentially.

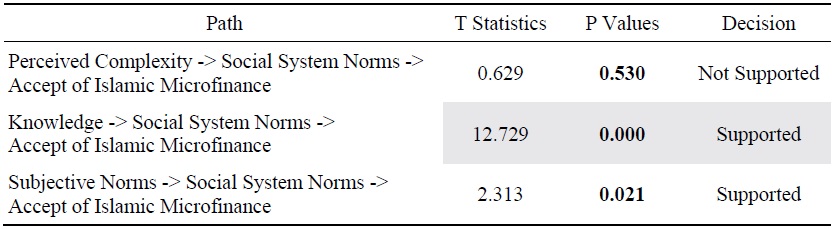

(3) Mediating effects

The P-value less than 0.05 refers to a significant relationship. In Table 10, except for perceived complexity, all other variables show the significant relationship of independent variables with dependent variables through mediating variables.

V. Conclusion

The research has focused on the factors that encourage women entrepreneurs to accept Islamic microfinance in Malaysia. In this study, the Theory of Planned Bahaviour model’s validity along with the Innovation & Diffusion Theory is also proved. On the basis of theory and collected data, the seven hypotheses are developed for the study. All hypotheses are validated by both directly and indirectly, as well as through a mediating factor. The study has investigated the effects of knowledge about Islamic microfinance, subjective norms, and perceived complexity on women entrepreneurs’ acceptance of Islamic microfinance in urban and rural areas of Malaysia. These outcomes indicate that knowledge about Islamic microfinance and subjective norms significantly influence the acceptance of Islamic Microfinance. On the other hand, the perceived complex does not show any substantial relationship to the acceptance of Islamic microfinance. Although the study has done a comprehensive study, there are two limitations. Firstly, the contribution of the research is constrained only to certain explanatory variables. Second, the study was confined to particular geography. Despite these limitations, the current study provides new insights into the factors contributing to the woman entrepreneurs’ acceptance of Islamic microfinance in urban and rural areas of Malaysia.

Tables & Figures

Table 1.

The Differences between Conventional and Islamic Microfinance

Source:

Figure 1.

Chinese EPU and ASEAN5 Stock Market Returns

Table 2.

Construct Reliability and Validity

Figure 2.

Measurement Model Assessment

Table 3.

Respondent Demographics Profile

Table 4.

Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Internal Consistency, and Convergent Validity

Table 5.

Fornell and Larcker’s Criterion

Figure 3.

Structural Model Assessment

Table 6.

Hypothesis Testing

Note: Significance level (*** p<.05, ** p<.10).

Table 7.

R-squared

Table 8.

F Square

Table 9.

Summary of Hypotheses

Table 10.

Mediating Effects

References

-

Abdelkader, I. B. and A. B. Salem. 2013. “Islamic vs conventional microfinance institutions: Performance analysis in MENA countries.”

International Journal of Business and Social Research , vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 219-233. -

Abdul Rahman, A. R. 2007. “Islamic Microfinance: A Missing Component in Islamic Banking.”

Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies , vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 38-53.https://doi.org/10.14989/70892 -

Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W. and M. H. Mohmad Sidek. 2017. “Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT Criterion.” Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on Applied & Industrial Mathematics and Statistics 2017 (ICoAIMS 2017). August 8-10, 2017. Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia.

Journal of Physics: Conference Series , vol. 890.https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/890/1/012163 -

Agwu, E. M. and A.-L. Carter. 2014. “Mobile phone banking in Nigeria: benefits, problems and prospects.”

International Journal of Business and Commerce , vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 50-70. - Ahlén, M. 2012. “Rural Member-Based Microfinance Institutions: A field study assessing the impacts of SACCOS and VICOBA in Babati district, Tanzania.” Bachelor’s Thesis 15 ECTS. Södertörn University.

-

Ahmed, H. 2002. “Financing microenterprises: An analytical study of Islamic microfinance institutions.”

Islamic Economic Studies , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 27-28. -

Ahmad, S., Lensink, R. and A. Mueller. 2020. “The double bottom line of microfinance: A global comparison between conventional and Islamic microfinance.”

World Development , vol. 136.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105130

-

Ajzen, I. 1991. “The theory of planned behavior.”

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 179-211.

-

Ajzen, I. 2005.

Attitudes, Personality and Behavior . Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill Education. -

Alavi, M. and D. E. Leidner. 2001. “Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues.”

MIS Quarterly , vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 107-136.https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

-

Allcott, H. 2011. “Social norms and energy conservation.”

Journal of Public Economics , vol. 95, no. 9-10, pp. 1082-1095.

-

Ameer, B. 2013. “Effectiveness of microfinance loans in Pakistan (A borrower perspective).”

Global Journal of Management and Business Research , vol. 13, no. C7. -

Ammar, A. and E. M. Ahmed. 2016. “Factors influencing Sudanese microfinance intention to adopt mobile banking.”

Cogent Business & Management , vol. 3, no. 1.

-

Ashrafi, H. 2017. “Micro Credit as a Poverty Alleviation Tool in Turkey: A Case Study Analysis of Turkish Grameen Micro Credit Project.”

Asian Business Review , vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 45-50.

-

Baber, H. 2019. “E-SERVQUAL and Its Impact on the Performance of Islamic Banks in Malaysia from the Customer's Perspective.”

Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business , vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 169-175.

-

Badri, A. Y. 2013. “The role of micro-credit system for empowering poor women.”

Developing Country Studies , vol. 3, no. 5. pp. 71-84. -

Bananuka, J., Kasera, M., Najjemba, G. M., Musimenta, D., Ssekiziyivu, B. and S. N. L. Kimuli. 2019. “Attitude: Mediator of subjective norm, religiosity and intention to adopt Islamic banking.”

Journal of Islamic Marketing , vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 81-96.https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-02-2018-0025

-

Brimah, B. A., Olanipekun, W. D., Bamidele, A. G. and M. Ibrahim. 2020. “Knowledge Management and its Effects on Financial Performance: Evidence from Dangote Flour Mills, Ilorin.”

Financial Markets, Institutions and Risks , vol. 4, no. 2.

-

Burtch, G., Hong, Y., Bapna, R. and V. Griskevicius. 2018. “Stimulating online reviews by combining financial incentives and social norms.”

Management Science , vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 2065-2082.

-

Chin, W. W. 1998. “Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling.”

MIS Quarterly , vol. 22, no. 1, pp. vii-xvi. -

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A. and R. R. Reno. 1991. “A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior.”

Advances in Experimental Social Psychology , vol. 24, pp. 201-234. -

Cicchetti, D. V. 1994. “Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology.”

Psychological Assessment , vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 284-290.

-

Cohen, J. 2013.

Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences . Routledge. -

Cooper, D. R. and P. S. Schindler. 2001.

Business Research Methods . New York: McGraw. -

Dahir, A. M. 2015. “The challenges facing microfinance institutions in poverty eradication: A case study in Mogadishu.”

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education , vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 56-62. -

Eagly, A. H. and S. Chaiken. 1993.

The psychology of attitudes . Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. -

Elmola, S. F. and I. Belal. 2013. “The impact of microfinance on rural poor households’ income & vulnerability to poverty: Case study of North Kordofan State.” Paper presented at the Tropentag 2013-Agricultural Development within the rural-urban continuum. September 17-19, 2013. Stuttgart-Hohenheim.

https://www.tropentag.de/2013/proceedings/proceedings.pdf -

Ferrao, P. J. and M. K. Price. 2013. “Using nonpecuniary strategies to influence behavior: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment.”

Review of Economics and Statistics , vol. 95, no. 1, pp. 64-73.

-

Fishbein, M. and I. Ajzen. 1975.

Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research . Mass.: Addison-Wesley Reading. -

Fornell, C. and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics.”

Journal of Marketing Research , vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 382-388.

-

Gerber, A. S. and T. Rogers. 2009. “Descriptive social norms and motivation to vote: Everybody's voting and so should you.”

Journal of Politics , vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 178-191.

-

Girabi, F. and A. E. G. Mwakaje. 2013. “Impact of microfinance on smallholder farm productivity in Tanzania: The case of Iramba district.”

Asian Economic and Financial Review , vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 227-242. -

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B. and V. Griskevicius. 2008. “A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels.”

Journal of Consumer Research , vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 472-482.

-

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. and M. Sarstedt. 2011. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet.”

Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice , vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 139-152.

-

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. and M. Sarstedt. 2013. “Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance.”

Long Range Planning , vol. 46, no. 1-2, pp. 1-12.

-

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. and R. E. Anderson. 2010.

Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective , 7th ed. New Jersey, US: Pearson Educatrion. -

Hameed, W. U., Basheer, M. F., Iqbal, J., Anwar, A. and H. K. Ahmad. 2018. “Determinants of Firm’s open innovation performance and the role of R & D department: An empirical evidence from Malaysian SME’s.”

Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research , vol. 8, no. 1.

-

Hameed, W. U., Mohammad, H. B. and H. B. K. Shahar. 2020. “Determinants of microenterprise success through microfinance institutions: A capital mix and previous work experience.”

International Journal of Business and Society , vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 803-823.

-

Hameed, W. U. and F. Naveed. 2019. “Coopetition-based open-innovation and innovation performance: Role of trust and dependency evidence from Malaysian high-tech SMEs.”

Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences , vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 209-230. http://jespk.net/paper.php?paperid=4335 -

Hanno, D. M. and G. R. Violette. 1996. “An analysis of moral and social influences on taxpayer behavior.”

Behavioral Research in Accounting , vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 57-75. -

Hartarska, V., Shen, X. and R. Mersland. 2013. “Scale economies and input price elasticities in microfinance institutions.”

Journal of Banking & Finance , vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 118-131.

-

Hasan, H. A. R. n.d. “Malaysia’s Economic Census 2011 and the Strengthening of Business register by Dr. Hj. Abdul Rahman Hasan Chief Statistician Department of Statistics, Malaysia.” Available at

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/info/meetings/eastasia/pdf/13pa1mys.pdf -

Hassan, S., Rahman, R. A., Bakar, N. A., Mohd, R. and A. D. Muhammad. 2013. “Designing Islamic microfinance products for Islamic banks in Malaysia.”

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research , vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 359-366. -

Hoyle, R. H. (ed.) 1995.

Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications . Sage Publications Inc. -

Hoyle, R. H. (ed.) 2011.

Structural Equation Modeling for Social and Personality Psychology , Sage Publications Ltd. -

Huda, N., Rini, N., Mardoni, Y. and P. Putra. 2012. “The analysis of attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control on muzakki's intention to pay zakah.”

International Journal of Business and Social Science , vol. 3, no. 22. pp. 271-279. -

Hussein Kakembo, S., Abduh, M. and P. M. H. A. Pg Hj Md Salleh. 2021. “Adopting Islamic microfinance as a mechanism of financing small and medium enterprises in Uganda.”

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development , vol. 28, no. 4, 537-552.

-

Ibrahim, A. H. and S. Bauer. 2013. “Access to micro credit and its impact on farm profit among rural farmers in dryland of Sudan.”

Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science , vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 88-102. -

Islam, M. A., Thambiah, S. and E. M. Ahmed. 2021. “The Relationship Between Islamic Microfinance and Women Entrepreneurship: A Case Study in Malaysia.”

Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business , vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 817-828.https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no5.0817 -

Kline, R. B. 2010.

Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press. -

Kivumbi. 2011. “The difference between Information and Knowledge.” DifferenceBetween.net.

http://differencebetween.net/language/difference-between-knowledge-and-information (accessed on December 21, 2022) -

Kumar, R., Ramendran, C. and P. Yacob. 2012. “A study on turnover intention in fast food industry: Employees’ fit to the organizational culture and the important of their commitment.”

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences , vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 9-42. -

Mansori, S., Chin, S. K. and M. Safari. 2015. “A shariah perspective review on Islamic microfinance.”

Asian Social Science , vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 273-280.

-

Mansori, S., Safari, M. and Z. M. M. Ismail. 2020. “An analysis of the religious, social factors and income’s influence on the decision making in Islamic microfinance schemes.”

Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research , vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 361-376.

-

McInerney, C. 2002. “Knowledge management and the dynamic nature of knowledge.”

Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , vol. 53, no. 12. -

Md Isa, F. Jaganathan, M., Ahmdon, M. A. S. and H. M. Ibrahim. 2018. “Malaysian Women Entrepreneurs: Some Emerging Issues and Challenges of Entering Global Market.”

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences , vol. 8, no. 12.https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i12/5261 - Morduch, J. and B. Haley. 2002. “Analysis of the effects of microfinance on poverty reduction.” NYU Wagner Working Paper, no. 1014. The Public Policy School of New York University.

-

Muchnick, J. and U. Kollamparambil. 2015. “Determinants of micro-finance repayment performance: a study of South African MFIs.”

Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences , vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 584-603.

-

Muhammad, H. 2020. “Islamic Corporate Social Responsibility: An Exploratory Study in Islamic Microfinance Institutions.”

Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business , vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 773-782.

-

Noipom, T. 2014. “Can Islamic Micro-financing Improve the Lives of the Clients: Evidence from a Non-Muslim Country.”

Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies , vol. 7, pp. 67-97.https://doi.org/10.14989/185835 -

Nolan, J. M., Schultz, P. W., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J. and V. Griskevicius. 2008. “Normative social influence is underdetected.”

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 913-923.

-

Obaidullah, M. 2008.

Role of Microfinance in Poverty Alleviation: Lessons from Experiences in Selected IDB Member Countries . Jeddah: IRTI, Islamic Development Bank. -

Obeid, H. and S. Kaabachi. 2016. “Empirical Investigation into Customer Adoption of Islamic Banking Services in Tunisia.” Journal of Applied Business Research, vol 32, no. 4.

-

Pareek, A. and P. Raman. 2016. “Payments Banks-Can India Achieve Digital Financial Inclusion.”

Global Journal of Business Management , vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 69-78. -

Parvej, M. M., Chowdhury, M. A. I., Azam, M. K. G., Hossain, M. M. and A. M. A. Mamun. 2020. “Role of Islamic Microfinance in Alleviating Poverty in Bangladesh: A Study on RDS of IBBL.”

International Journal of Financial Research , vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 111-129.

-

Purwanto, P., Abdullah, I., Ghofur, A., Abdullah, S. and M. Z. Elizabeth. 2022. “Adoption of Islamic microfinance in Indonesia an empirical investigation: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour.”

Cogent Business & Management , vol. 9, no. 1.

-

Rahman, A. R. A. 2010. “Islamic microfinance: An ethical alternative to poverty alleviation.”

Humanomics , vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 284-295.

-

Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H. and M. A. Memon. 2018.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using smartPLS 3.0 . Kuala Lumpur: Pearson. -

Robinson, E., Fleming, A. and S. Higgs. 2014. “Prompting healthier eating: Testing the use of health and social norm-based messages.”

Health Psychology , vol. 33, no. 9.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034213

-

Rokhim, R., Sikatan, G. A. S., Lubis, A. W. and M. I. Setyawan. 2016. “Does microcredit improve wellbeing? Evidence from Indonesia.”

Humanomics , vol. 32, no. 3.

-

Samer, S. Majid, I., Rizal, S., Muhamad, M. R., Sarah-Halim and N. Rashid. 2015. “The Impact of Microfinance on Poverty Reduction: Empirical Evidence from Malaysian Perspective.”

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , vol. 195.

- Schmidt, O. 2015. “Exploring the political economics of microfinance.” Paper presented at the 3rd Human and Social Sciences at the Common Conference.

-

Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J. and V. Griskevicius. 2007. “The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms.”

Psychological Science , vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 429-434.

-

Sekaran, U. and R. Bougie. 2016.

Research methods for business: A skill building approach . Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. -

Shirazi, N. S. 2014. “Integrating zakāt and waqf into the poverty reduction strategy of the IDB member countries.”

Islamic Economic Studies , vol. 22, no. 1. pp. 79-108.https://doi.org/10.12816/0004131

- Siddig, K. 2013. Role of women small enterprises in poverty alleviation in urban Sudan (1998–2012). Doctoral Dissertation. Alzaeem Alazhari University.

-

Sveiby, K. E. 2001. “What is knowledge management?” Sveiby’s Homepage.

https://www.sveiby.com/files/pdf/whatisknowledgemanagement.pdf (accessed on December 21, 2022) - Yousif, F., Berthe, E., Maiyo, J. and O. Morawczynski. 2013. “Best practice in mobile microfinance.” Grameen Foundation and Institute for Money, Technology & Financial Inclusion, University of California, Irvine.

-

Umar, U. B., Mas’ud, A. and S. A. Matazu. 2021. “Direct and indirect effects of customer financial condition in the acceptance of Islamic microfinance in a frontier market.”

Journal of Islamic Marketing , vol. 13, no. 9.

-

Wahyudi, I. 2015. “Realizing knowledge sharing in strategic alliance: Case in Islamic microfinance.”

Humanomics , vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 260-271.